At the end of 2012, there were 3,146 people on death row in the United States. Of the forty-five people executed last year, thirty-nine had been on death row more than ten years. In the last twenty-five years, the Innocence Project reports, at least eighteen death-row inmates have been exonerated and released.

Krishna Maharaj is seventy-four, a former Trinidadian millionaire of Indian descent who made his fortune importing bananas into Britain and spent it on Rolls Royces and thoroughbred horses. William Wayne Macumber is seventy-seven, a former engineer and the founder of a desert search-and-rescue team. Both men were put on death row for double murders. Both, according to new books, are innocent. Both are victims of a legal system so manifestly unfair that it inevitably fails.

At midday on October 16, 1986, a Jamaican entrepreneur, Derrick Moo Young, was shot dead, along with his twenty-three-year-old son, in room 1215 of the Dupont Plaza Hotel in Miami. The man immediately arrested for their murder, Krishna Maharaj, was Moo Young’s former business partner, but their partnership and friendship had recently ended over mutual accusations of swindling.

The prosecution had an excellent case: a gun, fingerprints, a witness turned state’s evidence, and a motive. The jury took no time to find him guilty of firearms possession, kidnapping, and murder. For the kidnapping, they recommended life imprisonment; for the murder, execution. It was election time in Florida and not a time for mercy. The judge gave Maharaj a death sentence.

In 1994, by which time Maharaj had been on death row for seven years, Clive Stafford Smith ’84LAW agreed to take his case. For the past thirty years, first in Atlanta and then in New Orleans, Stafford Smith has been a pro bono defender of poor people charged in death-penalty cases. Maharaj, now penniless, had reached the end of the appeals process and appeared to have very little room to maneuver. But there was just enough for Stafford Smith to suspect that justice had not been done.

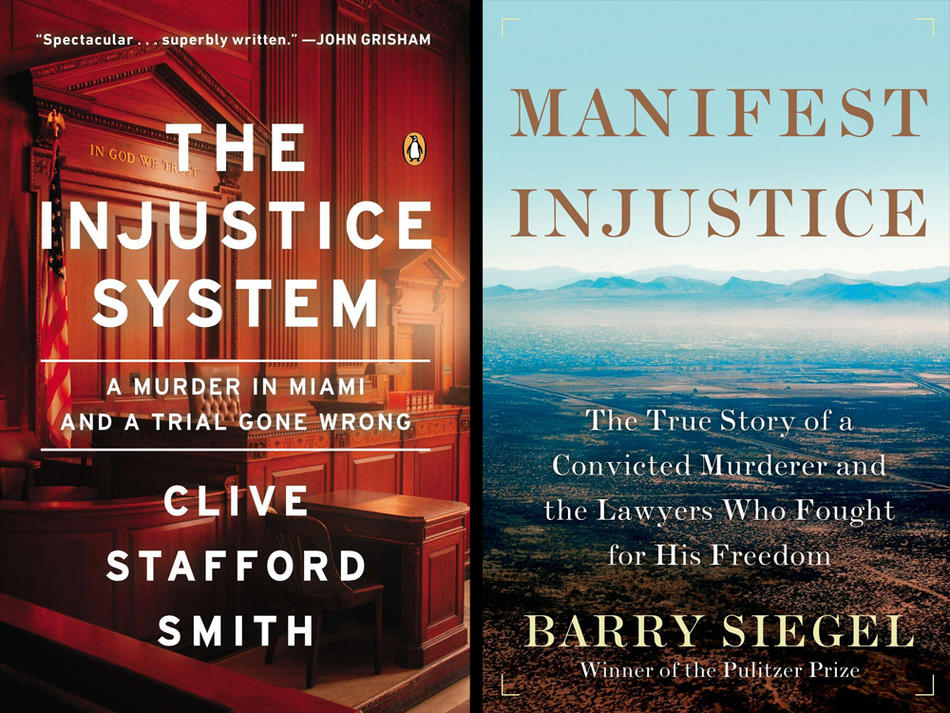

It did not take long for Stafford Smith to realize how profoundly unjust the verdict was. The more he dug, he writes in The Injustice System: A Murder in Miami and a Trial Gone Wrong, the more incompetence and skullduggery he found. Maharaj, sure that he would be acquitted, had hired his defense lawyer, Eric Hendon, because he was cheap. Hendon, says Stafford Smith, was inexperienced and idle; he and bits of useful evidence had “passed as ships in the night.” The prosecution, by contrast, had been canny and diligent — and corrupt. Key witnesses had been coaxed, details altered, testimony cleaned up, evidence suppressed or distorted. A first trial judge was charged with bribery in another case and stood down. A second proved indifferent and lazy.

Stafford Smith’s investigations took him to Panama and the Bahamas, into the world of drug cartels, laundered money, the trade in gold ingots and bonds, and finally to the conviction that the truth of the murder lay not with his client but in a complicated drug hit. The problem was how to prove it, given that it lay far in the past and involved a web of criminal associations in other countries. Though severely hampered by lack of funds, he did eventually secure a new hearing. In 1997, Maharaj was removed from death row.

But he was not freed. Further appeals ran afoul of a byzantine system of rules and laws “better suited to medieval law courts than to the 21st century.” Judges obfuscated and stalled. The case was rejected by the US Court of Appeals. As of March 2013, Maharaj, despite a wealth of fresh evidence of his innocence, the incompetence and corruption of earlier trials, and weighty testimonials from both sides of the Atlantic, remains a prisoner. No evidence ever seems quite enough. Unless dramatic fresh evidence is produced, and much new money raised, he will spend the rest of his life in prison.

William Macumber’s story is no less disquieting. On May 24, 1962, the bodies of Tim McKillop and Joyce Sterrenberg, both shot in the head, were found by their car, parked in the desert north of Scottsdale, Arizona. They were both twenty. There was talk of jealous suitors, robbers, enraged drivers, roving thrill seekers. Then a teenage addict came up with a story about a drinking and drug party at which a man had shot the two lovers. Two years later, Ernie Valenzuela, a twenty-year-old arrested on a charge of joy riding, confessed to the murders. However, through a combination of lack of evidence and police inertia, no further steps were taken.

Then, in 1974, Carol Macumber, in the throes of leaving her husband, approached the local sheriff’s office and claimed that he had confessed to the crime. She recalled a night in 1962 when he had come home with blood on his clothes, ostensibly from a brawl. William Macumber was arrested, released on bail, and brought to trial. As with Maharaj, there were large discrepancies over witnesses and evidence, as Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Barry Siegel ’72JRN recounts in Manifest Injustice: The True Story of a Convicted Murderer and the Lawyers Who Fought for His Freedom.

Ernie Valenzuela was now dead, killed in a prison fight, but before he died had again confessed to the murders. Yet because of technicalities governing what evidence was admissible, the county attorney was able to keep the confession from the court. Two attorneys and a ballistics expert, all in a position to exonerate Macumber, were not allowed to testify. The trial fell during the 1972–76 US moratorium on the death penalty, and Macumber was sentenced to life without parole. The diary he kept during these years is a painful record of fear, loneliness, and betrayal. Above all, he missed his three young sons, estranged from him by his wife, his letters to them returned unopened.

Macumber, again like Maharaj, was fortunate in attracting the attention of a nonprofit law project. He was represented by a remarkable and dedicated attorney named Larry Hammond and teams of young lawyers who succeeded each other over the years, passing down the baton along with a growing pile of new evidence. Macumber is clearly a likable man. His otherwise bleak existence was improved when a humane prison director allowed inmates to start sports groups and education projects, and he quickly rose to represent them on various state and national bodies. Not for long, though: a new director closed down the projects, saying that he did not believe in “coddling” prisoners. Macumber filled the long, lonely hours writing novels, poems, and local histories.

Eventually, the persistence of his defense team paid off. Though they were unable to secure release on grounds of a miscarriage of justice, a judge agreed that, in exchange for pleading no contest to two charges of second-degree murder, he would be freed under what is called post-conviction relief. Macumber, who has arthritis, emphysema, prostate problems, and a heart murmur, will not die in jail.

Both Maharaj and Macumber can be called lucky: they attracted the attention of tireless, clever, dedicated lawyers willing to spend hundreds of hours working for free on their cases. Even so, one of the men has spent twenty-six years in prison and remains there, and the other is free only after thirty-eight years. What makes these stories especially disturbing is the speed and ease with which the accused were convicted, on scant and often false evidence; their vulnerability in the hands of incompetent lawyers and chronically overworked public defenders; and the near impossibility of subsequently proving their innocence. When Columbia Law School professor Jim Liebman conducted a study of all 4,578 capital appeals heard between 1973 and 1995, he found serious errors in 68 percent of them. How many of the 3,146 people currently on death row are as innocent as Maharaj and Macumber?

As Stafford Smith argues, the lapses in the legal system do not happen by accident but because the system itself is arcane and flawed. Both books are not only gripping to read, but they present powerful arguments for fundamental reform. What they put on trial is America’s highly political, often corrupt, biased, inefficient, and unfair process that can lead a person to death. If either of these stories has an upside, it is in the dedication and selflessness of the dozens of men and women — lawyers, paralegals, neighbors, reporters, law students — who stepped forward to put the legal system itself in the dock.