In 2006, U.S. Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia boldly declared that there has not been “a single case — not one — in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit.” Perhaps an extensive new study by Columbia law professor James S. Liebman will force him to reconsider.

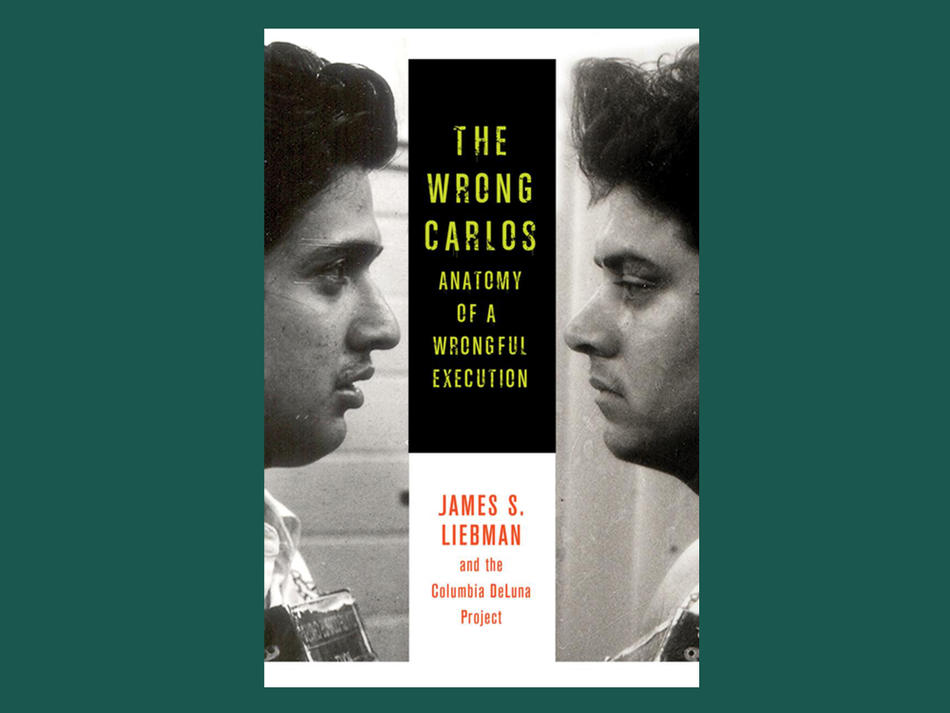

When Professor Liebman and a group of his students — Shawn Crowley ’11LAW, Andrew Markquart ’12LAW, Lauren Rosenberg ’11LAW, Lauren White ’11LAW, and Daniel Zharkovsky ’11LAW — first came across the case against Carlos DeLuna for the murder of Wanda Lopez, they had no idea that they would uncover such a clear-cut miscarriage of justice. Liebman had wanted to follow up on his findings that almost two-thirds of death-penalty verdicts in the last twenty-five years were overturned due to error. On the hunt for cases that rested on that least reliable type of evidence, eyewitness testimony, he started in Texas, where executions have been performed at nearly five times the rate of any other state since 1976 (according to the Death Penalty Information Center). His investigation, which included crime-scene photos, witness interviews, court records, and original news coverage, unfolds in The Wrong Carlos: Anatomy of a Wrongful Execution and its accompanying website, thewrongcarlos.net.

The tragedy began with Wanda Lopez, a convenience-store clerk in Corpus Christi, Texas, who was fatally stabbed while working the night shift on February 4, 1983. In less than an hour, police arrested twenty-year-old Carlos DeLuna after they found him hiding under a nearby truck. The state executed him just six years later. Yet from the moment of his arrest until the day he died, DeLuna maintained not only that he didn’t do it but that he knew who did.

As Liebman and his team of young legal scholars reconstruct the crime and resulting conviction in shocking detail, they forgo impassioned prose in favor of a facts-only approach. In doing so, they give readers the rare opportunity to dissect a capital case and “make up their own minds about the reality of wrongful executions.” The details tell a chilling story.

Carlos Hernandez was the same height and weight as Carlos DeLuna. The two men both lived in Corpus Christi and looked so much alike that friends and family mistook photos of one for those of the other. The jury would never learn the truth about DeLuna’s “tocayo,” or namesake: that he was notorious in the Corpus Christi community for his violence — often directed at poor Latino women — and that he had a penchant for Buck knives, like the one used to kill Lopez. When DeLuna named Carlos Hernandez as the real culprit, many, especially the jury, were doubtful. The prosecution maintained that they “exhausted all avenues to find Carlos Hernandez,” and that the “phantom” killer didn’t exist. But it was Hernandez, not DeLuna, who openly bragged about killing the young single mother.

Add to those key facts police cover-ups, prosecutorial misconduct, and a lack of DNA evidence, and it’s clear that Carlos DeLuna was sentenced to die based largely on one nighttime witness identification. By the time we reach the epilogue, Liebman explicitly says what most will have already concluded — that the state did not prove DeLuna’s guilt in the murder of Wanda Lopez beyond the shadow of a doubt. In fact, most of the evidence points to Hernandez, a vicious criminal who continued terrorizing his community until his death in 1999.

Though the authors suggest methods for improving the accuracy of evidence, the fact remains that no case is beyond human error. Moreover, the greatest opportunity for error seems to exist in cases involving those who live in relative obscurity, which only emphasizes the crucial role that race and class play in our justice system. Carlos DeLuna’s case went without reconsideration for almost twenty years.

As we follow the man described as a “slow thinker” preparing for his final day on “Death Roll,” Liebman reminds us that “we have no idea how many Carlos DeLunas there are among the well over 1,300 men and women executed since the reinstatement of the death penalty in the 1970s.” They can be found if the police, prosecutors, defense lawyers, and others summon “the curiosity and gumption to look just an inch or two below the surface.”