In May 17, 2003, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges approached the microphone on an outdoor stage at Rockford College in Illinois. It was a warm day, and around 2000 people, including 400 graduating students, had gathered in an open field on the school’s campus to hear Hedges deliver the Class of 2003’s commencement speech. Some sat in lawn chairs or on picnic blankets as gusts of wind riffled the grass and whipped the flags that were planted beside the speakers’ platform. There was an added sense of poignancy to this day of reflection and celebration: Just two months earlier, the United States and its allies had launched an invasion of Iraq, with virtually no opposition from Congress or the media; and with images like the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad’s Firdos Square and President Bush’s triumphal tail-hook landing aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln under a banner reading “Mission Accomplished” still fresh in the public mind — to say nothing of the events of September 11, 2001 — support for the Iraqi occupation was running high, especially in the heartland. It was against this backdrop that Hedges, a New York Times correspondent with much experience in war zones, opened his speech.

“I want to speak to you today,” he began, “about war and empire.”

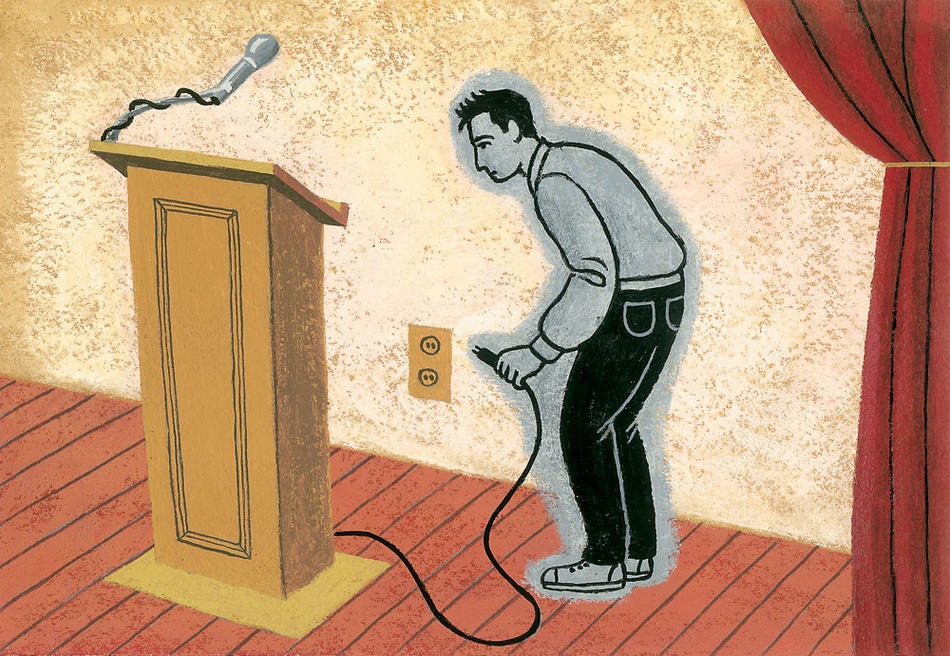

For the next 18 minutes, Hedges spoke of the moral and political perils of occupation, of the inevitable bloodshed to come, and of the insidiousness of the seduction of war. Not surprisingly, many in the crowd became agitated by Hedges’s words. Some stood and turned their backs, while others shouted, booed, blew foghorns, and erupted into chants of “USA! USA!” On two occasions, Hedges’s microphone was unplugged, prompting Rockford College President Paul Pribbenow to get up and make a brief speech on the importance of academic freedom. When Hedges, under a barrage of heckling, drew his remarks to an early close, several students climbed up onto the stage to confront him. The students were quickly escorted away, and Hedges, who had planned to stay for the entire ceremony, was hustled from the grounds by campus security.

Afterward, Hedges was skewered in the conservative press for America-bashing, while the hecklers were lauded for their patriotism. Talk-show host Sean Hannity called for Hedges to be fired from his job at the Times, and National Review managing editor Jay Nordlinger referred, in a column, to “that astonishing commencement address at Rockford College — the one that caused the students to revolt (bless ’em).” Pribbenow, the man who had invited Hedges, received death threats and had to change his phone number. Hedges himself expressed shock at the crowd’s reaction, telling radio host Amy Goodman of Democracy Now!, “I have certainly spoken at events where people disagreed — that is to be expected. But to be silenced and to have people clamber onto the platform with the threat of physical violence was something new, and frightening.”

Hedges, of course, was neither the first nor last guest speaker to be shouted down or silenced during an appearance on a college campus. That same year, television personality Phil Donahue’s commencement speech at North Carolina State University was repeatedly interrupted by jeers after he criticized the Iraq War. In 2002, the Stanford Israel Alliance disinvited Mideast scholar Daniel Pipes, citing controversy over Pipes’ Web site CampusWatch.org, which examines Middle East studies in North America from a pro-Israel perspective. This past fall, an event at Michigan State University featuring Colorado congressman Tom Tancredo, known for his staunch opposition to illegal immigration, was disrupted by boos and false fire alarms; and at Columbia, Jim Gilchrist, founder of a volunteer border-control group called the Minuteman Project, was unable to deliver a speech after protesters took to the stage with a banner, triggering a scuffle with Minuteman supporters.

The struggle to find the proper balance between expression and dissent on campus is at least as old as the Academy of Plato, where the Socratic method of debate formed the basis of philosophic inquiry (even as Plato himself argued for censoring poetry); and while there are no videos posted on the Internet to prove it, one imagines that not every dispute in the original groves of academe was sorted out as elegantly as in Plato’s dialogues. The logic is self-evident: Where there are ideas, there is disagreement; and the more ideas — including, by definition, unpopular or offensive ideas — the more potential for conflict.

The groves of Morningside Heights could hardly be an exception; for as University Provost Alan Brinkley tells us, few institutions encourage a freer flow of ideas than does Columbia.

“There are universities that have speech codes,” Brinkley says, by way of contrast. “There are universities that don’t allow certain kinds of speakers on campus. There are universities that put restrictions on the ability of student organizations to invite people to campus. And so on the scale of free speech at universities, we are way over to the most permissive, the most open side. We don’t have a speech code; we don’t want one. We aren’t afraid of controversy; we in fact welcome controversy. We aren’t afraid of speakers that might offend students, because we think from most speakers there is something to be learned. So that’s our policy, and that’s our tradition. And it makes for a turbulent community sometimes. That’s both the price and the benefit of our values and our policies.”

One can assume, then, that when a controversial speaker is heckled, booed, or silenced by angry students, it isn’t the school per se — or its president — that has acted censoriously.

Yet that was not the conclusion reached by much of the media in the aftermath of the Minuteman controversy of October 4, 2006. Because the event was videotaped and disseminated on the video-sharing Web site YouTube.com; because it took place at an Ivy League school with a history of student activism; and because, not least, the school is located just blocks from the nerve center of the national media, Columbia found itself on the defensive, as everyone from Bill O’Reilly of Fox News to Mayor Michael Bloomberg seemed to confuse the actions of a handful of protesters with official University policy. A New York Post editorial of October 6 entitled “Columbia’s Speech Thugs” charged that Columbia is “inhospitable to the First Amendment,” and asked, “Can it be true that free speech at Columbia applies only to those who are deemed ‘legitimate’ by a self-proclaimed group of political purists?” That the University allowed the College Republicans to host a divisive group like the Minutemen, as Brinkley suggests, rather belies the question’s premise; moreover, as President Lee C. Bollinger has often pointed out, the First Amendment does not apply to the University, since it is a private institution. Columbia voluntarily commits itself to the spirit of the First Amendment in setting its own policy for rallies, demonstrations, picketing, and the circulation of petitions. The University’s rules of conduct for “Demonstrations, Rallies, and Picketing” are laid out clearly in Appendix C of the Faculty Handbook (which covers faculty, students, and administrators); violators are subject to the sanctions described therein.

A tale of two students

“When people look at me and say ‘I hate you,’ or ‘Get off my campus,’ I just laugh,” says Chris Kulawik ’08CC. Kulawik, a history major, is the president of the Columbia University College Republicans. “You’re not going to change most people’s minds,” he says. “But there are some minds that I have changed.” Raised in the Westchester County suburb of Mount Kisco, New York, Kulawik comes across as a polite, respectful, clean-cut collegian fighting the good fight against what he sees as institutional discrimination against conservatives. “Professors,” he says, “don’t view us as their intellectual equals.”

It was Kulawik who invited three members of the Minuteman Project to speak on the subject of illegal immigration: Marvin Stewart, an ordained minister; Jerome Corsi, a Harvard PhD who coauthored the book Unfit for Command: Swiftboat Veterans Speak Out Against John Kerry; and Minuteman Project founder Jim Gilchrist. “At a meeting [of the College Republicans] last year, someone mentioned the Minutemen,” Kulawik explains. “Our thinking was, ‘Let’s bring some people who are citizen activists; they’re on the border, so let’s hear from them.’” And so in September, the College Republicans began posting flyers around campus announcing the event.

Around the same time, Karina Garcia ’07CC, who chairs the Chicano Caucus, was posting flyers for the Financial Aid Reform Coalition, a group in which she was active and which had petitioned Columbia to assist low-income families by replacing student loans with grants. In the course of leafleting, she came across a flyer announcing the scheduled talk by the Minutemen — a name she knew well, both as a native Californian (where the Minutemen originated, in 2004) and as the daughter of poor Mexican immigrants.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she says, recalling her reaction to the notice. “I was in complete shock.” Using her skills as an organizer, she reached out to such groups as Students for Economic and Environmental Justice, the Asian American Alliance, the International Socialist Organization, the African-American Student Association, and the College Democrats to form an anti-Minutemen front. The plan was to hold demonstrations in the days and hours leading up to the group’s appearance at the University.

Opinions about illegal immigration do not fall into neat political columns. On the right, cultural conservatives clash with free-marketers and business owners who rely on cheap labor; on the left, anti-population-growth environmentalists find themselves at odds with civil-rights advocates. The Minuteman Project’s nominal answer to the federal government’s failure to enforce existing immigration laws is for citizens to patrol the borders themselves and report suspicious or illegal activity to the proper authorities. And while the organization publicly disavows racism and violence, their mission statement warns that the United States is being “devoured and plundered by the menace of . . . invading illegal aliens,” which will result in “a tangle of rancorous, unassimilated, squabbling cultures,” leading inexorably to “political, economic, and social mayhem.”

Garcia believes that such words betray an agenda that has no place at a respectable university. “Terrorizing our communities, intimidation, and scapegoating,” she says, “are not up for academic debate. If the Minutemen were about debate, they wouldn’t be carrying guns, humiliating people, and harassing day laborers.” As Garcia speaks, her eyes begin to water; the pressures of post–October 4 media attention, along with hate mail, threats, and Internet name-calling (“thug,” “brownshirt,” “fascist,” “animal”) have clearly taken their toll. “This isn’t about just me,” she says. “It’s about my family. We don’t have to wait until there are thousands of people on the border with guns. The thing about Gilchrist is that his base is still the same people who are in the Klan and the National Alliance. Are we supposed to wait until they’re more powerful, or do we challenge these people now?”

A week before the scheduled speech, the College Republicans sent the Chicano Caucus an invitation to cosponsor the event.

“We wanted to ask if they’d like to get involved [with the event], help shape it,” Chris Kulawik says. When asked if the offer could have reasonably been interpreted, all things considered, as a political stunt, Kulawik answers without delay: “It would have been presumptuous,” he says, “to think that everyone in the Chicano Caucus shares the same opinions.”

The invitation was declined.

As October 4 approached, there was a growing feeling among students like Garcia that the planned protests outside Roone Arledge Auditorium were necessary not only to oppose what they saw as the forces of racism and xenophobia, but to show the world that the presence of the Minutemen on campus was in no way a reflection of the views of most Columbia students, or of the University itself; to answer Gilchrist’s arrival with signs and slogans, then, would be to defend the University’s honor.

“You’re doing a great job, kids”

Inside Roone Arledge Auditorium, the evening of October 4 began with a speech by Marvin Stewart, an African American whose membership in the Minuteman Project has been touted by Jim Gilchrist as evidence that the organization is not racist. Stewart’s speech lasted around 40 minutes and was repeatedly interrupted by catcalls, foot-stomping, and chanting by scores of students, including Karina Garcia. The speech was described by the Bwog (the blog of The Blue and White, Columbia’s undergraduate magazine) as a “free-associative rant, ranging through scripture and America’s Constitutional Republican form of government.”

When Stewart concluded his presentation, Gilchrist went over to him and gave him a hug, shouting to the audience, “Who’s the racist now?” From the lectern, Chris Kulawik chided the hecklers, saying, “I clearly had the false assumption that I was at an Ivy League school.” Amid shouts and boos, he introduced Gilchrist, who stepped to the microphone and said, “You’re doing a great job, kids. I’m going to have more fun with this than with my prepared speech.” After appearing to take a phone call from his wife, in which he referred to the audience as “the largest eclectic collection of social maladroits I’ve ever seen,” Gilchrist attempted to open his remarks. Just then, three student protesters appeared from behind the back curtain, holding a yellow banner that read “No Human Being is Illegal” in English, Spanish, and Arabic. This prompted several Minutemen supporters seated in the audience in front of Gilchrist to jump onto the stage and physically confront the protesters. The ensuing free-for-all, captured by Columbia University Television (CTV) and Univision, the largest Spanish-language television network in the U.S., was broken up by Columbia security officers. There were no serious injuries. The footage set off a frenzy of media attention, with the main actors, including Gilchrist, Kulawik, and Garcia, making the rounds on Fox News and elsewhere.

The framing of the October 4 narrative in the mainstream press was swift and unambiguous, echoing the story line of Fox and The New York Post: Student protesters rushed the stage, violently attacked Jim Gilchrist and Marvin Stewart, and shut down the event. The Los Angeles Times stated flatly that “The lectern was knocked over and Gilchrist fell back, smashing his reading glasses,” though the videotape and subsequent remarks by Gilchrist himself suggest otherwise. The New York Times was more circumspect, reporting that “organizers told several news agencies that the protesters who rushed the stage had knocked Mr. Gilchrist backward, causing his glasses to break.” The New York Sun, in an October 5 headline, declared, “At Columbia, Students Attack Minuteman Founder,” then went on to say, in the second paragraph, that Gilchrist and Stewart were escorted from the stage “unharmed.”

Samuel G. Freedman, New York Times columnist and professor of journalism at Columbia, thinks students would be wise to consider the surrounding media landscape before leaping onto a stage as big and conspicuous as Columbia’s.

“Personally,” he says, “I couldn’t have a lower opinion of the Minutemen. I think they’re a vile outfit. But if you’re going to get up on stage and attempt to intimidate even offensive speakers, you’ve created a news event, and you can’t then complain that you’re not getting sympathetic coverage.”

It’s a hard lesson that each new generation must learn, not least in the age of the Internet and 24-hour cable news: Some forms of dissent, no matter how well-intentioned, may prove counterproductive, inadvertantly strengthening the views they were designed to oppose. This is especially true when protest is aimed at speakers who have anticipated a particular reaction and are able to turn an audience’s hostility to their advantage. Whatever you think of the Minutemen, it can’t be denied that Jim Gilchrist knows how to work a room.

Strong opinions

Late on the night of October 4, the University released a brief statement deploring the disruption, while suspending further judgment until the facts were determined. Two days later, President Lee C. Bollinger, a noted First Amendment scholar, released a longer statement in which he affirmed the inviolable principle of permitting a speaker to speak, declaring that a society committed to free speech must maintain the courage to “confront bad words with better words.”

“We rightly have a visceral rejection of this behavior,” Bollinger wrote, “because we all sense how easy it is to slide from our collective commitment to the hard work of intellectual confrontation to the easy path of physical brutishness. When the latter happens, we know instinctively we are all threatened.” (On December 22, shortly before this magazine went to press, Bollinger released a new statement on campus speech issues. See sidebar on page 16.)

The October 6 statement did not please everyone. Some thought it didn’t go far enough in its censure of the protesters; others felt it was remiss in not apportioning blame to the Minuteman supporters, and would compromise the protesters’ ability to receive a fair hearing. Then there was Fox talk-show host Bill O’Reilly, who, on the October 6 edition of The O’Reilly Factor, had this to say, during an interview with Marvin Stewart: “Lee Bollinger, the president of Columbia, was invited on this program tonight to explain how this could happen at his university. This is not the first time this happened there. This is a radical-left university. Bollinger is hiding under his desk, as he always does.”

Though the possibility of his serving as the final avenue of appeal under the University Rules of Conduct would understandably preclude Bollinger from going on television and parsing the case with Bill O’Reilly (or anyone else), it is worth mentioning that, by conducting a thorough investigation at a pace less than rushed, Low Library ran the risk of appearing to some observers as hamstrung or indecisive.

Adding to this perception is that the University has been highly cautious with its public statements. (The normally critical Spectator, in an October 13 editorial, lauded this approach, saying that, “Throughout all this, it appears that the administration is the only party that has reacted thoughtfully.”) But among faculty — who are, of course, free to say anything they want outside the classroom — opinions about the rights of individuals on campus to speak and be spoken to weren’t so hard to find.

Todd Gitlin, professor of journalism and sociology at the Graduate School of Journalism, has an especially informed angle. While attending Harvard in the early 1960s, he was the national president of Students for a Democratic Society, a student activist movement whose members would play a key role in the student uprising at Columbia in 1968. Gitlin is sympathetic to the emotions of the October 4 protesters, and believes the Minutemen to be a racist organization, but he backs Bollinger’s view that speakers who have been invited to campus have a right to be heard. “I do take that to be something close to a sacred principle,” he says. “But that’s not to say that one must be silent at all times.”

The kinds of protest that are acceptable, as well as the intensity of their expression, may vary according to the situation, Gitlin says. This includes booing, heckling, waving signs, and unfurling banners. Still, he feels that students have become less diplomatic toward objectionable speakers than they used to be.

“In the early sixties, George Lincoln Rockwell [leader of the American Nazi Party] was being trundled around to speak at universities — I don’t know who was organizing it — and I don’t remember him being disrupted. Malcolm X, who of course had a big following but also had a lot of enemies, also gave lots of speeches at universities, and people heard him out. So I do think there’s a post-sixties sort of norm of incivility which is not lovely, and is regrettable.”

If Gitlin sees a range of behaviors that might fall under the legitimate rights of protesters, Vincent Blasi, who is Corliss Lamont Professor of Civil Liberties in the Faculty of Law, finds far less wiggle room.

“Those who claim a right to answer back or interrupt or turn this into a dialogue because they object to what the speaker is saying — I don’t think there is such a right,” Blasi says. “Some people would argue that that creates more enlightenment, and more ideas are in the air, and that serves the values of the First Amendment, but I think it’s pretty well established that part of what it means to have a First Amendment right is the right to have the conditions whereby you are speaking to people who have voluntarily chosen to listen to you without having to deal with chronic interruptions.”

At the same time, Blasi acknowledges that “the University is completely within its rights not to be consistent with the spirit of the First Amendment, to decide not to make its facilities available to outside speakers unless they are invited, according to some formal procedure, by university personnel — students, staff, faculty, or administration; and so you can limit the forum of the university to people who are members of that community. But if you choose not to, as Columbia does — if you choose to at least allow inside student groups to invite outsiders — then you have to be consistent. For a university to have different rules for different content of speech is problematic.”

Broadening the discussion

On November 16, 2006, the Student Affairs Caucus of the University Senate, which represents the entire student body of the University, released a report entitled “A Special Report on Free Speech at Columbia University.” The report’s author, Student Affairs Caucus chairman Christopher Riano ’07GS, wrote, “The Caucus is looking to enlarge the debate we are having among students to include faculty and administration, as well as inform the community of the importance we attach to this topic.” While no firm consensus was found within the student body as to exactly what considerations and requirements should be incumbent upon guest speakers and those who invite them, Riano stresses that there is a “majority opinion that students, and student organizations, should have the right to invite whomever they wish to Columbia to speak on topics of their choosing.”

Even so, students are divided as to whether an open policy toward guest speakers necessarily serves the University’s overarching goals of fostering learning and scholarship, as some speakers may not seem to serve any obvious academic purpose.

Still, as Riano’s report suggests, the debate over free speech on campus has long been won by those affirming its indispensability. But discussion of its meaning and implementation — how to strike a fair balance between competing rights and responsibilities — continues. Alan Brinkley, for one, sees in the dispute an intellectual opportunity.

“I think what happened at the Minuteman event represented, at least in part, a lack of understanding among students and perhaps others of what constitutes free speech,” Brinkley says. “Free speech generally, but free speech at a university like Columbia in particular. So to the degree that this event generated conversation and inquiry into what that means, and to the degree that we’re able to keep that inquiry going, that would be a positive thing.”

Plato would agree.