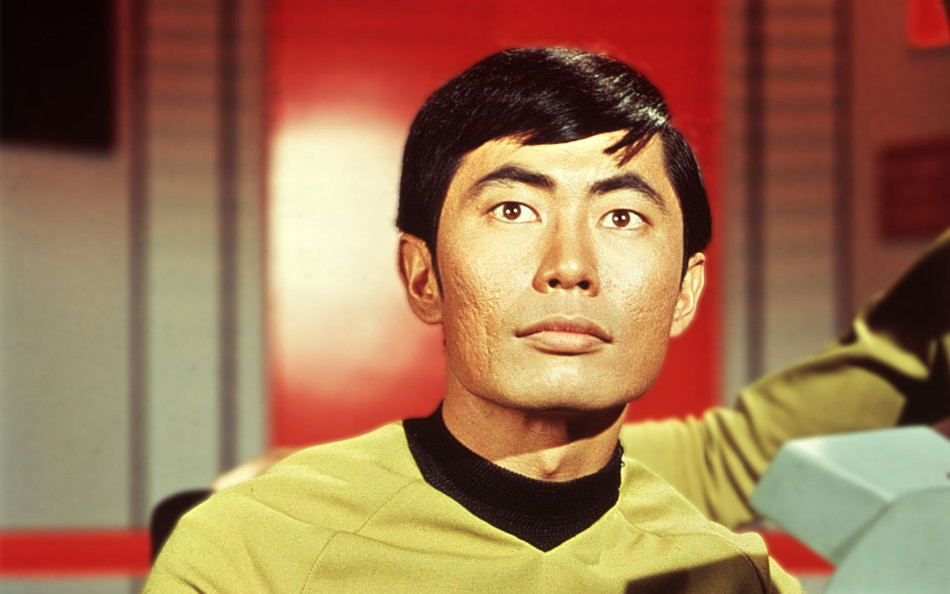

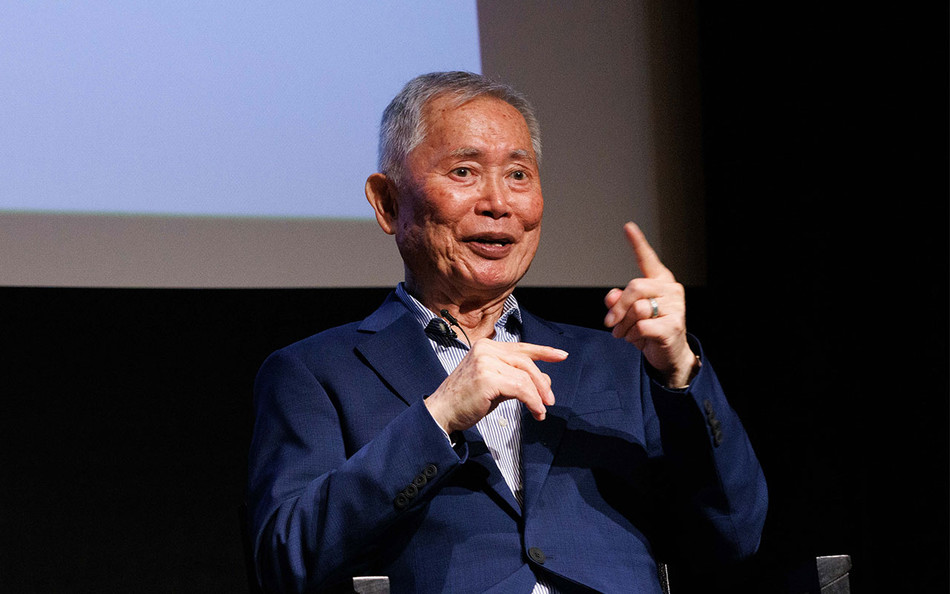

A slide presentation of joyous wedding photos might seem a strange prologue for a talk about internment camps, but George Takei knows how to open a show. On a recent Thursday, Takei, who played Sulu on the TV series Star Trek (1966–1969), was at Miller Theatre to deliver the 2021–22 Soshitsu Sen XV Distinguished Lecture on Japanese Culture, sponsored by the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture. As part of the last surviving generation of Japanese-Americans interred during World War II, Takei has dedicated himself to bringing awareness to one of the grimmer chapters in US history. And as a gay man who came out at age sixty-eight and is now, at eighty-three, a vocal advocate for LGBTQ rights, Takei has an intimate understanding of history’s curving arc.

Once the slideshow of Takei’s 2018 nuptials to his husband, Brad, had ended, Keene Center director Haruo Shirane, the Shincho Professor of Japanese Literature and vice chair of the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, introduced Takei to cheers. In his sonorous basso, Takei shifted the scene from the celebration of his wedding day to the gravity of a childhood trauma that was also a national one.

Born in East Los Angeles to immigrant parents, Takei was four years old when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. And he was five in May 1942 when, gazing out the window of his house, he saw two soldiers carrying rifles with fixed bayonets walking up the driveway.

Three months earlier, in February, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ’08HON had signed a wartime measure that permitted military authorities to round up potential domestic enemies. Now, in the Takei living room, the soldiers ordered the family — Takei, his parents, his four-year-old brother, and his infant sister — to leave. Eighty years later, Takei could still picture his crying mother, a duffel bag over her shoulder and a baby in her arms.

The family was taken to the Santa Anita racetrack in Arcadia and housed in a fetid horse stall while camps were being prepared to hold some 120,000 Japanese-Americans. After four months, the Takeis were placed on a train bound for Arkansas and deposited behind the barbed wire of the Rohwer Japanese-American Relocation Center.

One day, Takei said, the adult prisoners were asked to renounce their fealty to the Japanese emperor. Takei’s parents refused, since they had no such fealty, but “no” was the wrong answer: they were labeled disloyal and sent to a more repressive camp in Northern California, where tanks rolled around the perimeter and soldiers pointed machine guns at the detainees. Then, in the summer of 1945, news arrived that the US had bombed Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Takei’s mother’s had family in Hiroshima and suffered a breakdown. (Later she learned that her sister and five-year-old niece had been killed.)

Takei was eight when he was released. After three years in the camps, the Takeis were given twenty-five dollars apiece and a one-way ticket to Los Angeles, where they lived in the Skid Row district. Takei’s father opened a dry cleaner and was active in local politics until his death in 1979. Takei expressed regret that his father didn’t live to see President Ronald Reagan sign the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, in which the US government apologized for the “grave injustice” of the internment of Japanese-Americans.

A capstone of Takei’s journey came in 2015, when President Barack Obama ’83CC hosted a state dinner at the White House for Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe. Takei was invited. He sat next to the prime minister’s wife, and next to her was Obama.

There was someone else there, too: Brad. He was seated next to Nancy Pelosi.

“This,” Takei told the Miller Theatre crowd, “was the America I love. This was the America I want to be a part of.”

Then Takei, who last spoke at Columbia in 2016 in a conversation with theater professor David Henry Hwang, responded to audience questions. He said that he first realized he was gay at age nine; that his Star Trek castmates knew he was gay (“actors are very sensitive”), except for William Shatner (“it went right over his head”); that these actors, knowing that word of Takei’s sexuality could destroy his career, never mentioned it. He came out in 2005 after California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed a marriage-equality bill. “From that point on, I was out and active,” he said.

With more than three million Twitter followers, Takei takes action just by moving his thumbs, and his tart, funny comments on matters of the day have made him one of the country’s foremost digital opinionators. Some of his followers were in the Miller audience, and when the program concluded, Takei basked in their applause.

Just then, a boy named Zander, the son of Keene Center assistant director Yoshiko Niiya ’93BC, appeared onstage holding two bouquets of red and yellow flowers. He approached Takei, who responded to the proffered gift with a look of shock and delight.

Takei took the bouquets, cradled them in his arm, and faced the room with a wide, beaming smile. “I feel like Miss America!” he said.