Twenty years ago, James Hansen made global warming a political issue almost overnight. The Columbia professor told a Senate committee he was “99 percent certain” that pollution was already warming the earth, causing droughts and heat waves. Lawmakers had to “stop waffling” and deal with the problem, he vented to reporters as he left the Senate chamber.

Never before had a prominent climate scientist argued publicly that global warming was under way. Hansen’s testimony made headlines around the world and the “greenhouse effect” a household term. Within weeks, several members of Congress had sponsored bills aimed at regulating carbon dioxide emissions and George H. W. Bush promised to mobilize the international community to fight global warming if he was elected president.

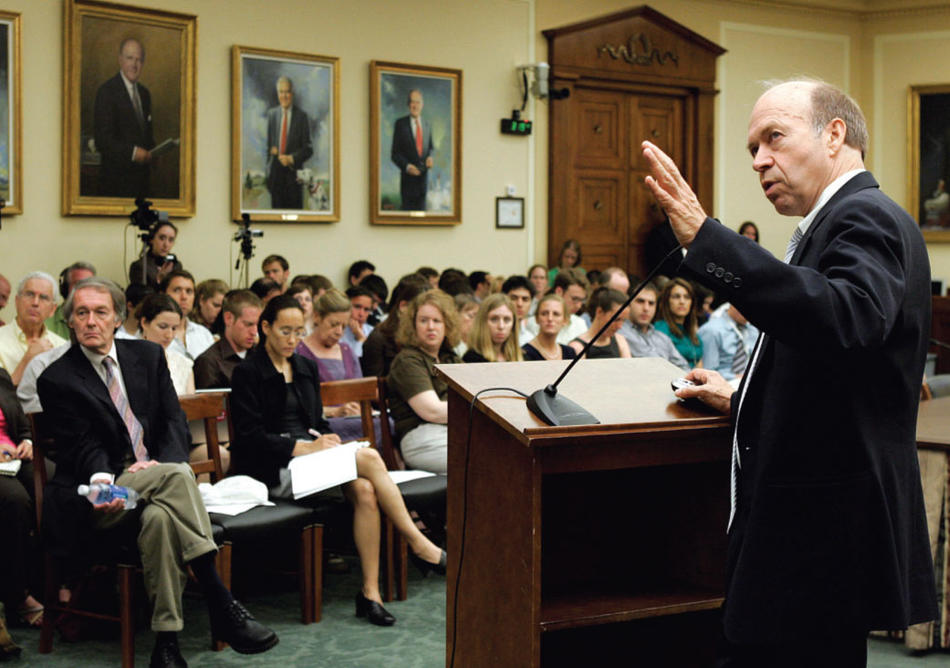

Hansen returned to Capitol Hill on June 23, the 20th anniversary of his famous testimony, to update lawmakers on the state of the planet. He spoke at a special hearing organized in his honor by Representative Edward Markey (D-MA), who called Hansen “a hero.”

What’s changed in 20 years? “The difference is that now we’ve used up all slack in the schedule for actions needed to defuse the global warming time bomb,” said Hansen, who directs NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, a Columbia affiliate. He accused Congress of having done too little to promote alternative energy or limit greenhouse gas emissions. Progress has been blocked, he said, because coal and oil companies have convinced the public that the basic science of global warming is in dispute.

“CEOs of fossil energy companies are aware of the consequences of what they are doing,” said Hansen, 67, in his calm, midwestern accent. “These people should be tried for crimes against humanity.”

What should lawmakers do? Stop construction of coal plants until technology can suck the carbon dioxide out of their smoke stacks, Hansen said, and develop a nationwide grid for alternative energy, such as from wind- and solar-powered generators.

“A path yielding energy independence and a healthier environment is, barely, still possible,” he said. “It requires a transformative change of direction in Washington in the next year.”