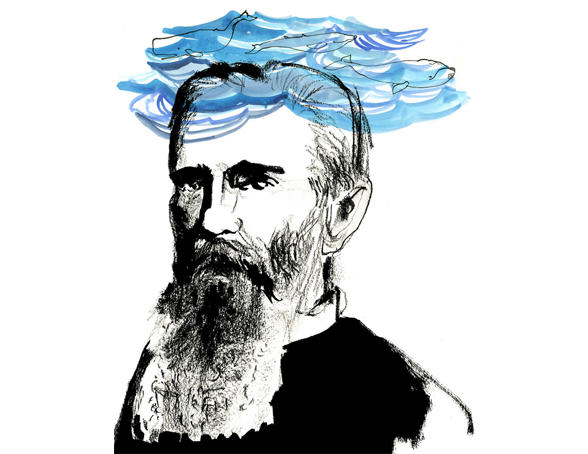

How Scholars Rescued the Author of Moby-Dick from the Waters of Oblivion

1919 was a big year for literary centenaries. James Russell Lowell, poet, critic, and diplomat, was feted at Columbia University and the Ritz-Carlton, and Walt Whitman was toasted by two hundred at the Hotel Brevoort, near Washington Square. Both writers had been born in 1819, and both had been dead for thirty years.

So had Herman Melville. The difference was, Melville had sunk from view. His first two books, Typee and Omoo, based on his voyages to the South Pacific, made a splash in the late 1840s. Then, in 1851, Melville calved an enormous spouting beast of a book, Moby-Dick, which involved a crazed sea captain hell-bent on destroying the whale that tore off his leg. The book sold poorly. After two more failed novels, Melville, a father of four, ditched prose for poetry, grew ever more melancholic and insolvent, and became a customs inspector on the New York docks, a job he held for nineteen years. His death in 1891 went virtually unnoticed.

“Melville was a nineteenth-century author writing for a twentieth-century audience,” explains Columbia professor Andrew Delbanco, author of the 2005 biography Melville: His World and Work. “He used stream of consciousness long before Stein or Joyce; he acknowledged America’s predatory power as well as its great promise; he defied convention in writing about sex; and perhaps most shocking of all, he took seriously the possibility of a godless universe. In his time, there was a limited market for these insights and innovations.”

But in 1919, one American critic knew of the buried treasure. Carl Van Doren 1911GSAS, a professor of English at Columbia and literary editor of the Nation, wanted to mark Melville’s centenary in the magazine. He had a writer in mind: an English instructor named Raymond Weaver 1917GSAS, whose mastery of Shakespeare was a good prerequisite for tackling the American writer who in language and spiritual turbulence most closely approached the Bard. At Van Doren’s urging, Weaver dusted off Melville’s works and was hooked.

“Essentially he was a mystic, a treasure-seeker, a mystery-monger, a delver after hidden things spiritual and material,” Weaver wrote in the August 2, 1919, Nation. “It was Melville’s abiding craving to achieve some total and undivined possession of the very heart of reality.”

Weaver embarked on a biography, Herman Melville: Mariner and Mystic, that would be published in 1921. The same year, Van Doren published The American Novel — essays on Hawthorne, Twain, James, and also Melville, whose seventy-year-old whaling masterpiece Van Doren and Weaver were now raising like a lost ship. Van Doren wrote of “the extraordinary mixture in Moby Dick of vivid adventures, minute details, cloudy symbolisms, thrilling pictures of the sea in every mood, sly mirth and cosmic ironies, real and incredible characters, wit, speculation, humor, color.”

After this, Moby-Dick became a celebrated mainstay of the American canon. Robert Wallace ’72GSAS, ’67SIPA, a professor at Northern Kentucky University who has taught Moby-Dick for half a century, calls it “an encyclopedia of world knowledge at the time” and says students today draw lessons that the previous generation didn’t. “They are thrilled that Ishmael, in telling this story of the brutality of whaling, finds ways to express the beauty of whales and how they represent the natural world that we’re in the process of destroying.”

Though Moby-Dick looms over all American literature, Melville produced other pearls, and Weaver uncovered one of them. While researching his biography, Weaver visited Melville’s granddaughter Eleanor Melville Metcalf at her home in New Jersey. Metcalf showed Weaver a trunk of Melville’s papers, which included a manuscript in Melville’s inscrutable hand. The writer had been working on a short novel before his death. It was never published.

Weaver edited the manuscript and included it in a sixteen-volume edition of Melville’s works published in 1924. The novel, Billy Budd, concerns a handsome, innocent sailor who is recruited onto a British warship, where the wicked master-at-arms Claggart mercilessly goads him until Billy finally erupts: he strikes Claggart, accidentally killing him — and must face, under maritime justice, the supreme penalty. Weaver called the novel “unmatched among Melville’s works in lucidity and inward peace” and found in the tragedy an unsuspected grace: “The powers of evil and horror must be granted their fullest scope; it is only thus we can triumph over them.”

Weaver, who worked at Columbia for thirty-two years, was a passionate teacher whose interests included mask-making and astrology. Lionel Trilling ’25CC, ’38GSAS called Weaver’s death in 1948 an “irreparable loss,” but today, Weaver’s legacy is stronger than ever. This year, Herman Melville’s bicentennial was honored worldwide. None of this could have been predicted in 1919, but in his Nation essay, Weaver, the amateur astrologist, took a stab at divining Melville’s future.

“The versatility and power of his genius was extraordinary,” Weaver wrote. “If he does not eventually rank as a writer of overshadowing accomplishment, it will be owing not to any lack of genius, but to the perversity of his rare and lofty gifts.”