In one of his last essays, left unfinished at his death in 1975, Lionel Trilling tried to understand “Why We Read Jane Austen.” Trilling started wondering about Austen’s lasting appeal, he writes, because of the extraordinary popularity of a seminar on Austen that he offered at Columbia in 1973. There was room for 20 students in the class, but on the first day, “to my amazement and distress,” 150 showed up. Trilling could only explain this enthusiasm as a sign that Austen had become one of that select group of writers who “can be called ‘figures’ — that is to say, creative spirits whose work requires an especially conscientious study because in it are to be discerned significances, even mysteries, even powers, which . . . bring it to as close an approximation of sacred wisdom as can be achieved in our culture.”

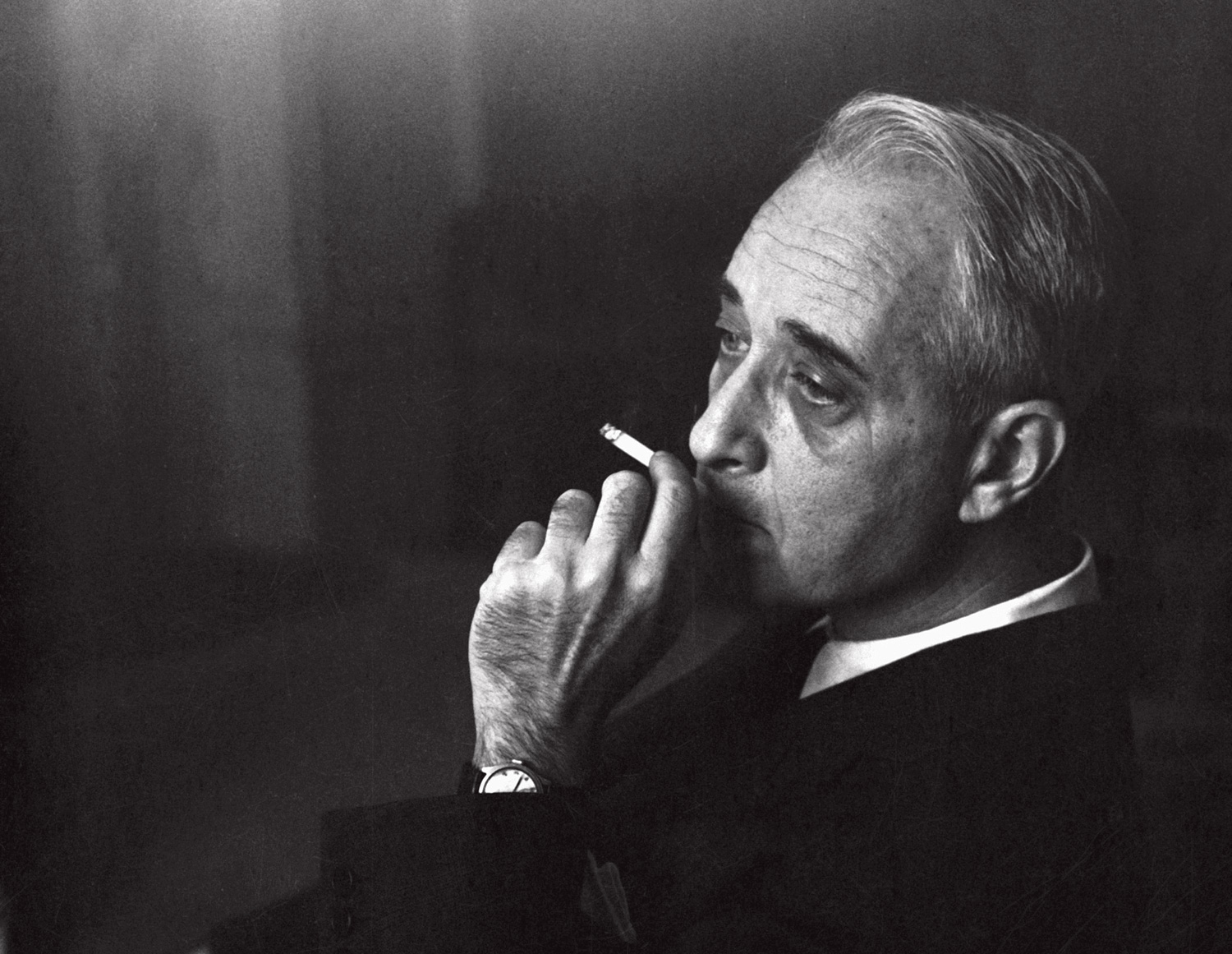

Trilling ’25CC, ’38GSAS was too modest to suggest, or maybe even to recognize, another reason for the interest in his Austen seminar: that he himself had become a figure in American culture. To generations of students at Columbia, where he spent almost his entire career, starting as an undergraduate in the 1920s, and to many more who knew him through his essays and books, Trilling was more than a great literary critic: He was a symbol of the life of the mind in America. Like a handful of other professors in midcentury Morningside Heights — Jacques Barzun, Richard Hofstadter, Meyer Schapiro — Trilling wrote at the intersection of the academy and the wider culture, in the belief that literary and critical ideas mattered to society at large.

His best-known book, The Liberal Imagination (1950), collected his essays on subjects ranging from Henry James to the Kinsey Report, demonstrating how the kind of intelligence cultivated by the study of literature, with its virtues of “variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty,” was essential for the health of democracy. For Trilling, true liberalism often meant resisting the certainties of right-thinking liberals, whether the pro-Soviet views of the 1930s Popular Front or the antinomian spirit of the 1960s.

“Liberal intellectuals have always moved in an aura of self-congratulation,” he wrote. “They sustain themselves by flattering themselves with intentions and they dismiss as ‘reactionary’ whoever questions them. When the liberal intellectual thinks of himself, he thinks chiefly of his own good will and prefers not to know that the good will generates its own problems, that the love of humanity has its own vices and the love of truth its own insensibilities.” That is why Trilling was especially drawn to writers like Matthew Arnold and E. M. Forster, the subjects of his first two books, who criticize liberalism from within. He was also a great, though not uncritical, admirer of Freud, whose work he read less as science than as “grim poetry” about the contradictions of human nature.

Yet the very things that made Trilling so compelling to his original readers have conspired, in the decades since his death, to turn much critical opinion against him. It wouldn’t really be fair to say that Trilling is a marginal figure today. Most of his work is still in print — the essays gathered in The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent and his only finished novel, The Middle of the Journey. In 2008, Columbia University Press even published the incomplete manuscript of another novel, edited by Geraldine Murphy ’85GSAS, as The Journey Abandoned. Every time Trilling’s work is reissued, it is greeted with long, serious discussions in leading magazines.

The tone of these discussions tends to be a peculiar combination of nostalgia and disdain, with a strong undercurrent of “goodbye and good riddance.” Critic and University of Cambridge professor Stefan Collini, writing about Trilling in a deliberate parody of Trilling’s own style, captured the mood best: “There is, for many of us, something vaguely oppressive about the thought of having to reread Lionel Trilling now. . . . We can’t help feeling that we should be improved by reading Trilling, and this feeling itself is inevitably oppressive. . . . Reading him keeps us up to the mark, but we can’t help but be aware that the mark is set rather higher than we are used to.”

Clearly, Trilling has been assigned the role of literature’s superego. As a student of Freud, he could have predicted what must follow, for if the superego is the savage enforcer of unattainable cultural ideals, then the ego’s health and happiness require that it be humbled. That is why so much recent writing about Trilling focuses on the failure of his hope of becoming a great novelist, on his private doubts about his teaching and criticism, on the moments of unhappiness he confided to his journals. Pitying a writer is an excellent way of undermining his authority.

But this kind of semi-Oedipal rebellion against Trilling only makes sense for those readers and writers who remember him as a stern presence in the world of letters. By now, 36 years after his death, that is a shrinking group. Like most readers under the age of 40 or even 50, I have no personal memory of Trilling, or of a literary culture in which he was a figure of authority. On the contrary, when I was an undergraduate English major in the mid-1990s, I don’t believe Trilling was ever assigned or discussed in any of my courses. I first came to him on my own, and, though I found people to encourage my enthusiasm, I always read Trilling for pleasure, not from obligation.

Part of the pleasure, certainly, came from the authority of Trilling’s judgments, and of the prose that conveys those judgments. When he writes, in “Manners, Morals, and the Novel,” that “the novel . . . is a perpetual quest for reality, the field of its research being always the social world, the material of its analysis being always manners as the indication of the direction of man’s soul,” we can sense the ambition and precision of his mind at work. Indeed, Trilling’s authority, like all genuine literary authority, is itself a literary achievement. It is not a privilege of cultural office or a domineering assertion of erudition and intellect, but an expression of sensibility, the record of an individual mind engaged with the world and with texts.

This is true of all the best literary critics, but it seems especially true of Trilling, who was surprisingly uninterested in the traditional prerogatives and responsibilities of criticism. In his major essays, he does not bring news of important new writers or teach us how to read difficult new works — the way that, for instance, Edmund Wilson did. If Trilling’s essays are not exactly literary criticism, it is because they are something more primary and more autonomous: They belong to literature itself. Like poems, they dramatize the writer’s inner experience; like novels, they offer a subjective account of the writer’s social and psychological environment. And like all literary works, Trilling’s essays are ends in themselves. This helps to explain why there has never been a Trilling school of criticism. He does not offer the reader findings or formulas, which might be assembled into a theory; he offers what literature alone offers, an experience.

It is a kind of experience that today’s serious readers and writers are hungry for. Over the last 10 or 15 years, many of the institutions that once sustained literature in America have changed or disappeared, including independent bookstores and newspaper book reviews. In the last couple of years, this process has reached its ultimate conclusion with the disappearance of the book itself, the site and symbol of literature for 500 years. Margaret Atwood expressed the anxiety of many readers at this development: “This is crucial, the fact that a book is a thing, physically there, durable, indefinitely reusable, an object of value . . . electrons are as evanescent as thoughts. History depends on the written word.”

Over the same period, literature itself began to suffer a crisis of confidence. Poetry, of course, was the first to go. Already in 1991, in his essay “Can Poetry Matter?” Dana Gioia declared that “American poetry now belongs to a subculture. No longer part of the mainstream of artistic and intellectual life, it has become the specialized occupation of a relatively small and isolated group.” Five years later, Jonathan Franzen lamented in his essay “Perchance to Dream” that whatever attention the novel continued to receive was just “consolation for no longer mattering to the culture.”

At such a moment, readers and writers could be forgiven for thinking that “we are all a little sour on the idea of the literary life these days. . . . In America it has always been very difficult to believe that this life really exists at all or that it is worth living.” But, in fact, it was Lionel Trilling who made this complaint, some 60 years ago, right in the midcentury moment that we remember now as a golden age. And this suggests why Trilling, in particular, has so much to say to us today.

“Generally speaking,” he pointed out, “literature has always been carried on within small limits and under great difficulties.” What sustains writers and readers under those difficulties is, above all, the consciousness of one another’s existence. This is, in fact, the consolation that Franzen finds at the end of “Perchance to Dream”: “In a suburban age, when the rising waters of economic culture have made each reader and each writer an island, it may be that we need to be more active in assuring ourselves that a community still exists.”

The name of the activity by which readers and writers communicate, by which they make the private experience of reading into the common enterprise of literature, is criticism. And Trilling is the critic who best demonstrates what it means to read seriously — how the encounter with the ideas and attitudes we find in books can help us create our selves. As he wrote in “Manners, Morals, and the Novel,” one of his most famous essays, “For our time the most effective agent of the moral imagination has been the novel of the last 200 years. . . . Its greatness and its practical usefulness lay in its unremitting work of involving the reader himself in the moral life, inviting him to put his own motives under examination. . . . It taught us, as no other genre ever did, the extent of human variety and the value of this variety.”

Trilling’s criticism shows what it means for a book to involve a reader in the moral life. When Trilling reads Henry James’s novel The Princess Casamassima, he confronts the ethics of political violence and the psychology of radicalism; when he reads Mansfield Park, he wonders about the nature of virtue in a post-religious society; when he reads the letters of Keats, he takes courage from the poet’s trust in the world’s sensual abundance. Again and again in his essays, Trilling shows that the literary life is really the same enterprise that Keats called “soul-making.” Now that Trilling is no longer such a name to conjure with, it is possible that a new generation of readers will find that he matters more than ever.