A tiny town has sprung up in the Georgia woods. Call it Binderville. Or The Small Apple. Population 150. The town sits in the middle of Stone Mountain State Park, near Atlanta, on an otherwise vacant parking lot surrounded by forest. And it is home to some very unusual people.

Forty-odd trailers are parked in rows, forming improvised blocks, lanes, neighborhoods. Portable satellite dishes are angled outside the doors. Meat sizzles on a grill that someone fired up this mild February day. From windows come snippets of Russian, Spanish, German, French. Three children, fresh from the trailer that serves as their school, race scooters across the asphalt, their shouts piercing the low hum of the generators at the edge of the lot. Pet dogs wander the grounds, inured to the rousing scent of horses that spices the air. Nearby, a barrel-chested Chinese man in sunglasses sits on a folding chair and calmly smokes a cigarette. In a few hours, he will, like his father before him, lift a large ceramic vase over his head and do things with it that defy both gravity and description.

His feat, and those of his neighbors, will be witnessed by hundreds of people inside the big, castle-shaped, royal blue Italian-made tent that is the very hub of Binderville. The town encircles the blue castle, with its cupolas and yellow pennants, just as, not far away, tall trees surround the great outcropping of granite that is Stone Mountain. In Binderville, you see, circles are everything.

As the sun goes down, the sky gains a purple gray tint, ringed with a band of pale orange. A stream of cars, filled with parents and children, begins to flow into the lot. The trailers empty out, and everyone — jugglers, acrobats, clowns, aerialists, musicians, riggers, dog handlers, lighting designers — heads toward the castle.

Paul Binder, founder and longtime ringmaster and artistic director of the Big Apple Circus, sums up his life’s journey this way: “My story again and again is that I followed the things that were compelling to me — what other people described as ‘following my passion.’” How else would a kid from Brooklyn who idolized Danny Kaye grow up to study European history at Dartmouth, get his MBA from Columbia, become a world-class street juggler, join a French circus, and then go on to create one of the most prestigious circuses in the world?

“Now this was a little crazy,” Binder says from the couch of his trailer on the lot of Stone Mountain Park. “Here’s this guy with two Ivy League degrees, experience in the world of television [between his studies, Binder had been a stage manager for Julia Child and a talent coordinator for Merv Griffin], and now he has the notion of, ‘Hey, wouldn’t it be great to be a juggler?’”

In 1971, Binder went on a trip to San Francisco, the “Athens of the counterculture,” where he saw a performance of the San Francisco Mime Troupe. He was instantly hooked, and, having done some comic theater as an undergrad, auditioned for the troupe using a Danny Kaye piece that he had seen in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. One of the judges on the audition committee was Michael Christensen, who would later become cofounder of the Big Apple Circus. “The mime troupe was really important because they had this circus training program,” Binder says. “I learned to juggle there, and I built an act with Michael, who was also learning to juggle.”

Binder and Christensen traveled to England in 1974. In a barn in Kent, they polished their routine for 10 days, then took the show to the streets. Literally juggling for their meals, they worked their way from London as far eastward as Istanbul, by way of France and Italy. But the hand-to-mouth life of the traveling street performer began to take its toll.

“So we’re standing on the banks of the Bosporus, and there was a boat that for 10 kurus could take us to Asia,” Binder recalls. “I had tears in my eyes, I was sobbing, and I said, ‘Michael, we are not getting on that boat. That’s it. We’re not going any farther east than this.’ I think it was a metaphor for my sanity: across the water lay madness.”

They turned around and ended up in Paris, where they were seen performing on the street by the choreographer Roland Petit, who owned the Casino de Paris, a music hall where he had developed an old-style Parisian revue. Petit hired “Paul and Michael” to be in the spectacular, which starred Petit’s wife, Zizi Jeanmaire. The show aired on French TV, and the jugglers got noticed again.

“As the story goes,” says Binder, “Pierre Étaix, who was married to the famous clown Annie Fratellini, was watching the show, and he saw us and said, ‘Annie! Annie! Viens ici! You’ve got to see this!” The next day we got a message to call Annie Fratellini. She invited us over and said that she and her husband were starting a circus, the Nouveau Cirque de Paris, and they would like us to work with them. So we did a special show with her and Pierre Étaix, and eventually we did a tour of France with the Nouveau Cirque. That was my first experience in the circus, and it absolutely captured me.”

It all comes back to those circles.

“Circus means circle, and that became a guiding light to me,” Binder says. “I came to understand that this form, this circle where the community sits and responds as a group, is a very primal theatrical form. In ancient societies, the community gathered in a circle and acted out their hopes and dreams and aspirations. They resolved their survival fears. And the circus, in which artists are working on the edge of hope and fear and aspiration, very closely resembles that. We had nothing like that in our experience in theater back home. So I thought, ‘How would we create this for New York? How would we create this for America?’ I had this powerful sense of social service and that performance art could be a wonderful transformative experience for people, and out of that came the earliest conception of the Big Apple Circus.”

The Big Apple Circus opened in 1977, in a tent on the landfill that later became the site of Battery Park City, in the shadows of the World Trade Center.

“From the beginning,” says Binder, “I understood that there was no way we could create this social enterprise and have it be a profit-making organization. It had to be supported by the community, so we set out to find that support. Our earliest sponsor was Con Edison.” Fitting for an operation that produced its own sort of electricity: a traditional European one-ring circus, set under a big top rather than in a sports arena, in which the audience is close enough to see the color of the trapezist’s eyes.

Within three years, the circus moved to Damrosch Park at Lincoln Center. The relocation had two important consequences: It defined the space for the circus, pushing but not exceeding the limits of theatrical intimacy that Binder wanted to bring to American audiences. And it demanded an unending search for topflight talent.

“If we were going to be the circus for New York City, appearing with the Metropolitan Opera on one side and the New York City Ballet on the other,” Binder says, “we had to have the kind of quality that would justify that.”

In addition to scouting and recruiting virtuosic acts from all over the world (“I pride myself in being a great talent hunter”), Binder served as artistic director of the circus until stepping down this year. At 66, “Mr. Paul,” as he is known on the lot, has decided to focus his energy where it is needed most.

“We’re looking at serious issues about how we’re going to survive,” he says. “Not just our ticket revenue, which we’re afraid is going to go down, but also our fundraising. The funders of the world are making decisions right now, in the arts in particular but in not-for-profits in general, about who survives the bad economic times. It’s a heavy way of saying it, but it’s real.”

With 180 employees (including the road crew, administrative staff, and community programming staff), an additional 95 clowns who work in the circus’s renowned “Clown Care” program, and an annual operating budget “just north of $20 million,” the Big Apple Circus has long relied on the support of thousands of individuals, corporations, foundations, and government agencies. Now, says Binder, “I am at the point in my career where I want to guarantee that there’s a next generation of the Big Apple Circus. My role, going forward, is to find the people who will make sure that’s the case.”

And it’s not just the magic of the ring that Binder wants to preserve; it’s what the circus does outside the tent.

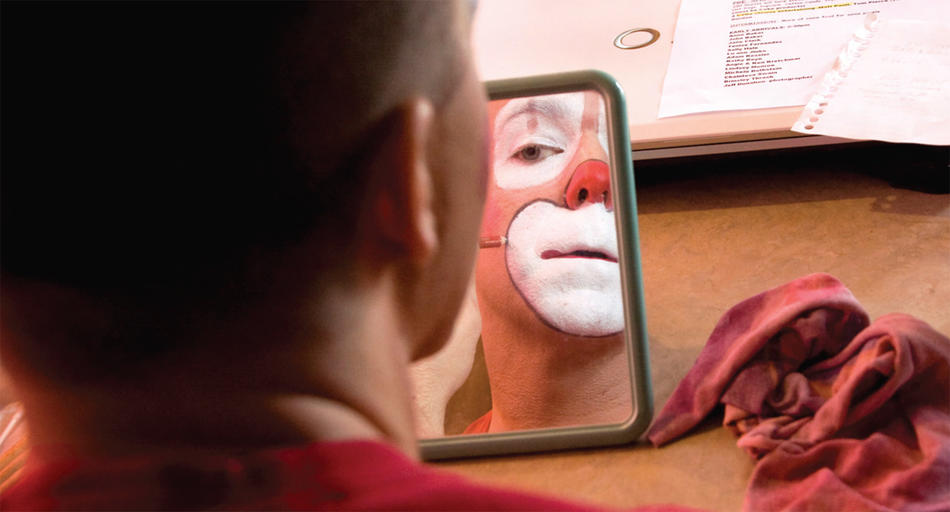

“Michael Christensen discovered that performing with and for kids in hospitals had an amazing effect on them, and he established this notion of a clown care unit,” Binder explains. “Now, we’re in 19 hospitals nationwide, 7 in New York City. It is a wonderful program. These are professional performers who are trained in the technique of working in hospitals, which is a very special form. Everybody wins — the patients, the parents, the nursing staff, and the clowns themselves. We believed that if we focused on our service to the community, the community would be the stewards of the organization, and that it would be in the interest of the community for the Big Apple Circus to flourish.”

With 31 seasons and counting (each season lasts from September to July), the “little circus that could” already has survived three recessions, as well as pressure from animal rights groups over its use of elephants. (The circus stopped using elephants in 1999, and now employs only dogs and horses.) Still, the current economic downturn poses an immense challenge, making the title of this year’s show, “Play On,” seem as much a showbiz battle cry as its intended meaning: a salute to Binder’s love affair with music, which began when he was a boy.

“The happiest days of my childhood were when my father, who was a salesman, would walk around the house playing the violin,” Binder says. “To this day it goes to the deepest part of me.” It’s also what motivates Binder’s creativity: an urge to share his sense of beauty with the world. “If only you could see how beautiful it is,” he pleads, expressing his driving emotion, so removed from the realm of balance sheets. “If only you could know what it feels like when your daddy plays the violin.”

The seats under the big top have begun to fill up. The brightly painted set — red, green, orange, blue, yellow — includes a giant treble clef and a whimsical musical staff strung with luminescent notes. An eight-piece pop ensemble convenes on the multiplatform bandstand, which lights up in jukebox colors. A pair of mischievous clowns warms up the audience with pranks and ballpark cheerleading. In the midway, people make last-minute purchases of popcorn and blue cotton candy, then rush back up the ramp to take their seats.

A peculiar tension builds, enhanced by the rigging, high above the ring, of all sorts of ropes and pulleys and cables, like the innards of some ingenious contraption, the strings of some perfect mechanical thing whose calibrations leave no room for error.

Soon, the houselights go down, and Paul Binder, in red tails, strides into the ring and greets the crowd. After concluding some funny business with Grandma the Clown, a circus mainstay played by Barry Lubin, Binder strikes this year’s theme: “If music be the food of love,” he intones, quoting from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, “play on!”

The opening number is a Broadway-style explosion of dance and music and sparkling tutti-frutti costumes. There are twin jugglers and high-flipping gymnasts, daredevil equestrians and sequined ladies of the high wire. It’s as if a giant game of Candy Land has burst to life. The exuberance carries the force of the intrepid nature of the performers — soon these people will be flying through the air and riding horses upside down.

Among these acts are the incredible LaSalle Brothers, identical twins Jake ’07CC and Marty ’07CC, whose teen-heartthrob looks and breathless juggling-and-gymnastics routine suggest what might have happened had onetime Columbia student Troy Donahue been cloned, handed some balls, and sent to the Moscow Circus School. The brothers dance, do backflips, turn cartwheels, and soar over each other’s shoulders — all while juggling Indian clubs in exhilarating synchronization.

Each act of the Big Apple Circus delivers its own peculiar thrill, pushes a slightly different button in one’s nerve center. There’s the sultry artistry of wire walker Sarah Schwarz, the extreme equilibrium of the Nanjing Duo (woman goes en pointe on man’s head) and our vase balancer Guiming Meng, and the jaw-dropping athleticism of the Rodion Troupe, in which acrobat Anna Gosudareva is hurled high in the air from a five-inch-wide barre held on the shoulders of two men, turns multiple somersaults, and lands perfectly on the rail. And then, suddenly, the heart-stopping rush of a magnificent horse as it leaps into the ring! The golden palomino gallops at full thrust around the sawdust perimeter, blond mane flowing, eyes bulging, great head tilted at a windy angle as its Kazakh rider, Sultan Kumisbayev, vaults, spins, and rides with his head inches from the ground, just like the Cossacks. Wow!

At intermission, adults and kids rush to get more popcorn or else head for the portable toilets (“donnickers” in carnival parlance). A child asks her mother how that man caught that giant vase with his head. “Practice,” the mother says wisely.

There will be many such questions on this evening, many excited recitations of moments as the crowd exits, headlights ablaze, into the cool Georgia night.

Soon after, the castle will empty, the small windows of Binderville will light up, and a soft rain will fall on the big top and on the asphalt and the roofs of the trailers. And in three weeks the little town will fold its tent and form a caravan back north to New Jersey, Boston, Queens, Long Island.

But why look that far ahead? There is still more circus to come: clever dogs, capering clowns, and, of course, the men and women of the flying trapeze.

As people return to their seats, Paul Binder, dressed in his street clothes, walks the aisles, and, with the solicitude of a restaurateur engaging his patrons, chats with folks in the audience. He asks one gentleman what he thought of the first half of the show.

“Fantastic!” the man says, with obvious delight. “Wonderful!”

This pleases Binder enormously: It’s music to his ears. He flashes a broad smile and holds his fist at his hip, as if ready to break into a soft-shoe. “To paraphrase Al Jolson,” he says, in his showman’s baritone: “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet!”

Brother Act

With twin Jugglers Jake and Marty LaSalle, the future is up for grabs.

One day when he was nine years old, Jake LaSalle went with his mother to an apple orchard in his native Pennsylvania. Most little boys, upon picking apples, might be inclined to eat them, or throw them at a squirrel. Jake had another instinct. Though he had never seen a juggler before, he started tossing the apples into the air, one, two, three at a time, keeping them aloft, or trying to, as if this were the perfectly natural thing to do with such objects.

Excited by his discovery, Jake went home and taught the trick to his twin brother, Marty. “Within a year,” Jake says, “our parents took us to the circus and bought us a juggling book.” The brothers, who already had been training in gymnastics, soon developed an unusual brand of acrobatic juggling. In 2001, at the International Jugglers’ Association Championship in Madison, Wisconsin, the duo won first prize. Offers followed from variety theaters throughout Europe, but instead the brothers enrolled at Columbia. (They both graduated cum laude in 2007.)

Though their academic interests vary — Jake studied anthropology and took pre-med courses; Marty studied economics — inside the ring they enjoy a kind of kinetic telepathy that may or may not have to do with their biological connection.

“I feel that people have an internal rhythm,” Jake says. “With juggling teams, you can see that some people are a little slower or a little faster, and their rhythms are slightly off. But with Marty and me, we’re always the same. And I think that the precision we’ve developed is largely a result of our being able to communicate intuitively. We’re twins, but we’ve also been working together since we were kids. If something goes wrong, it’s as if we know immediately how to recover, regardless of what happens.”

What Jake describes as a “motivational, mutually reinforcing” partnership will be tested when the current circus season ends. Jake has been accepted to several medical schools, including the College of Physicians and Surgeons, which means that the LaSalle Brothers likely will go on indefinite hiatus. That’s a hard pill to swallow for their fans.

Jake tells of an encounter with Austin Quigley, dean of Columbia College, who attended the Big Apple Circus at Lincoln Center this winter with his wife and grandchildren.

“It was such an honor to meet him,” Jake says. “I don’t know what I was expecting him to say, but I told him I was going to medical school, imagining he’d be more enthusiastic about that than our performance. And he said, ‘I feel that I should be encouraging you guys not to give this up.’”

Fortunately, they won’t have to.

“You throw yourself into something so intensely for so long, and it never leaves you,” Jake says. “Even if I’m not physically doing it, this experience will enrich me for the rest of my life.”