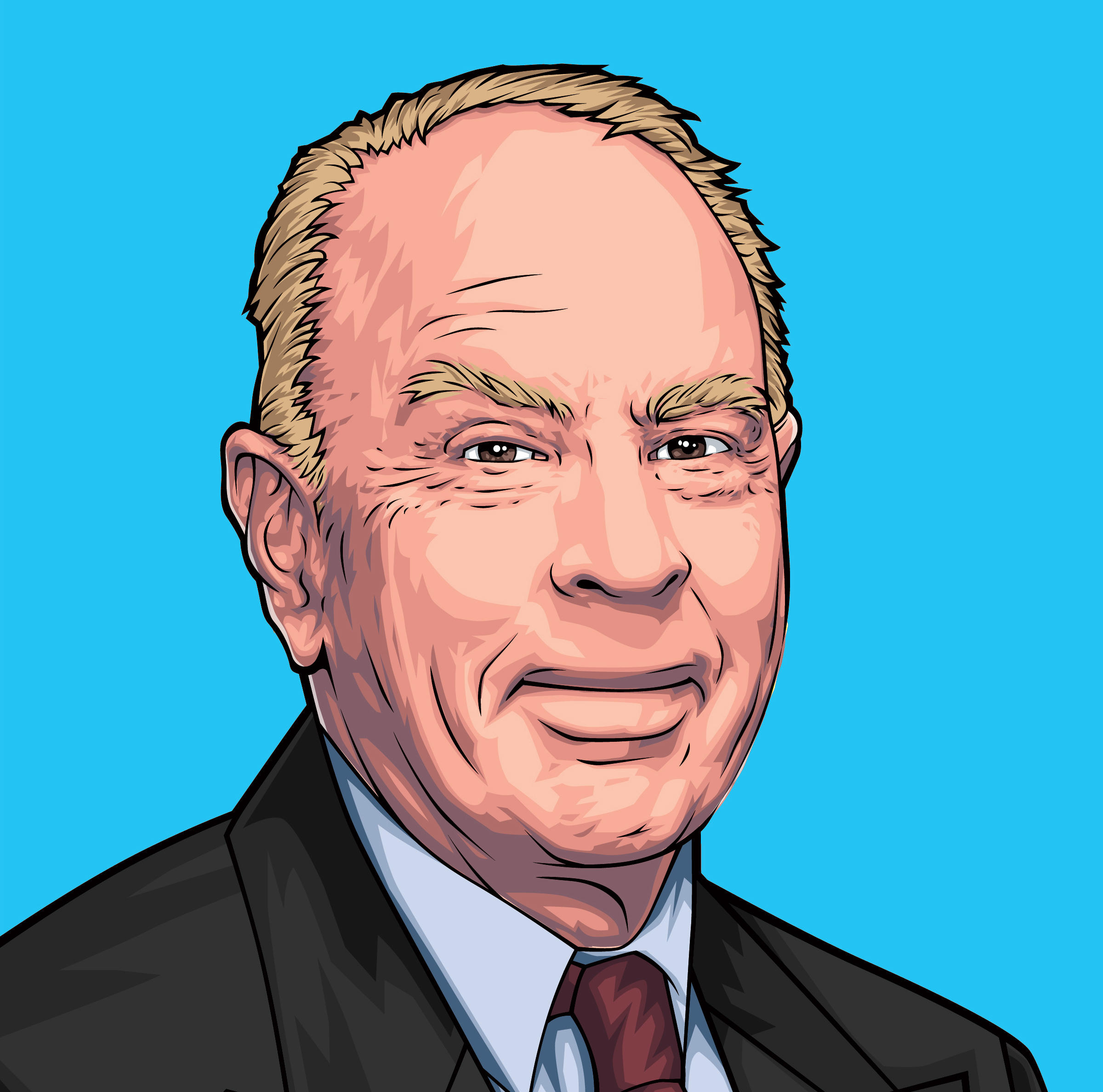

Many people have heard of the Southern Poverty Law Center, but who is Morris Dees?

Dees is an Alabama-born white man who made a fortune in the direct-mail business. He grew up in a culture of white supremacy and got his start in public life working on a campaign for George Wallace, the notorious segregationist who became Alabama’s governor and ran for president. Dees, who was also a lawyer, successfully defended a Klansman charged with beating Freedom Riders in Montgomery. But step by step his views evolved, and he became one of the country’s leading civil-rights litigators and a founder of an organization that has about forty lawyers working on human-rights issues in the South.

“The Epic Courtroom Battle” is a catchy subtitle, but the lawsuit that shut down the United Klans of America is just a section of your book.

True — the book is an intricate story of the history of the civil-rights movement through the lives of Dees, Wallace, and Robert Shelton, the Klan’s clever and manipulative leader. Shelton helped incite the lynching of a random Black man, Michael Donald, over the mistrial of a Black defendant accused of killing a white police officer. I had to do a lot of research to weave those three stories together to show how the South was changed and what it took to make that happen.

You’ve written fifteen books, including biographies of very disparate people: Johnny Carson, the Kennedys, Arnold Schwarzenegger. Have you found any common threads?

Yes, there’s a moral complexity to all of them. And Morris Dees is the ultimate example of that. He’d like to think of himself as Atticus Finch, that saintly fictional character in To Kill a Mockingbird. But he’s more like Oskar Schindler, the real-life hero of the Spielberg film who’s a womanizer and greedy guy who ends up saving more than a thousand Jews. People tend to see important figures as either saints or devils. Almost no one is one or the other.

Your professors at the journalism school sent you to cover Wallace on the night of the 1968 presidential election. How did that come about?

In November of 1967, while I was bored to death studying international affairs at the University of Oregon, I talked my way onto Wallace’s plane and spent a few days with him. The New Republic published an article I submitted cold, and then Student magazine sent me to Alabama. When I came to Columbia the next fall, the professors asked me to do their election-night radio coverage in Montgomery. I put my Columbia banner up there with ABC and CBS. They thought I was broadcasting across the nation. It was just to a classroom at Columbia!

Is what you learned about Wallace relevant to the 2016 election?

Yes. Donald Trump and Wallace have many similarities. Wallace was a brilliant politician, certainly in his understanding of the white working class, particularly in the South. He knew segregation inevitably would end. But he figured he could rise to power as its most militant defender. In the same way, Trump knows he’s not going to throw eleven million people out of this country and stop Muslims from coming here. But it was a great issue when he was starting out and he didn’t have any traction. They’re similar, too, in liking to bring crowds to the edge of violence.

You interviewed former Klansmen, including some who went to prison for the lynching. How did that go?

It was scary, frankly. I’d go out in the countryside and knock on doors, and most of the time it was the wrong person. I thought, “Why the hell am I doing this at this age?” but I had to find these people. To the Klansmen, those were the most exciting days in their lives, so they were willing to talk about it after all these years. They knew they weren’t going to get in any more trouble.

How did you get started on Dees?

He called me and said, “I’ve got a project that’s been sitting here all these years. Would you like to do it?” He promised total access to the files and total control of the writing, and he kept his word. There are many things in the book that would upset a lot of guys. Morris didn’t flinch.