They would become legends — their names etched on the syllabuses of literature classes everywhere, their books reprinted and shoved in the back pockets of teenagers ripe with wanderlust, their words devoured, memorized, heeded, imitated.

But before the night of August 14, 1944, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg ’48CC, and William S. Burroughs weren’t the three principals of a literary movement — at least, not one that existed outside their own heads. They were simply roommates, friends, and confidants, who shared books and booze and sometimes beds. And, as history would largely soon forget, there was a fourth.

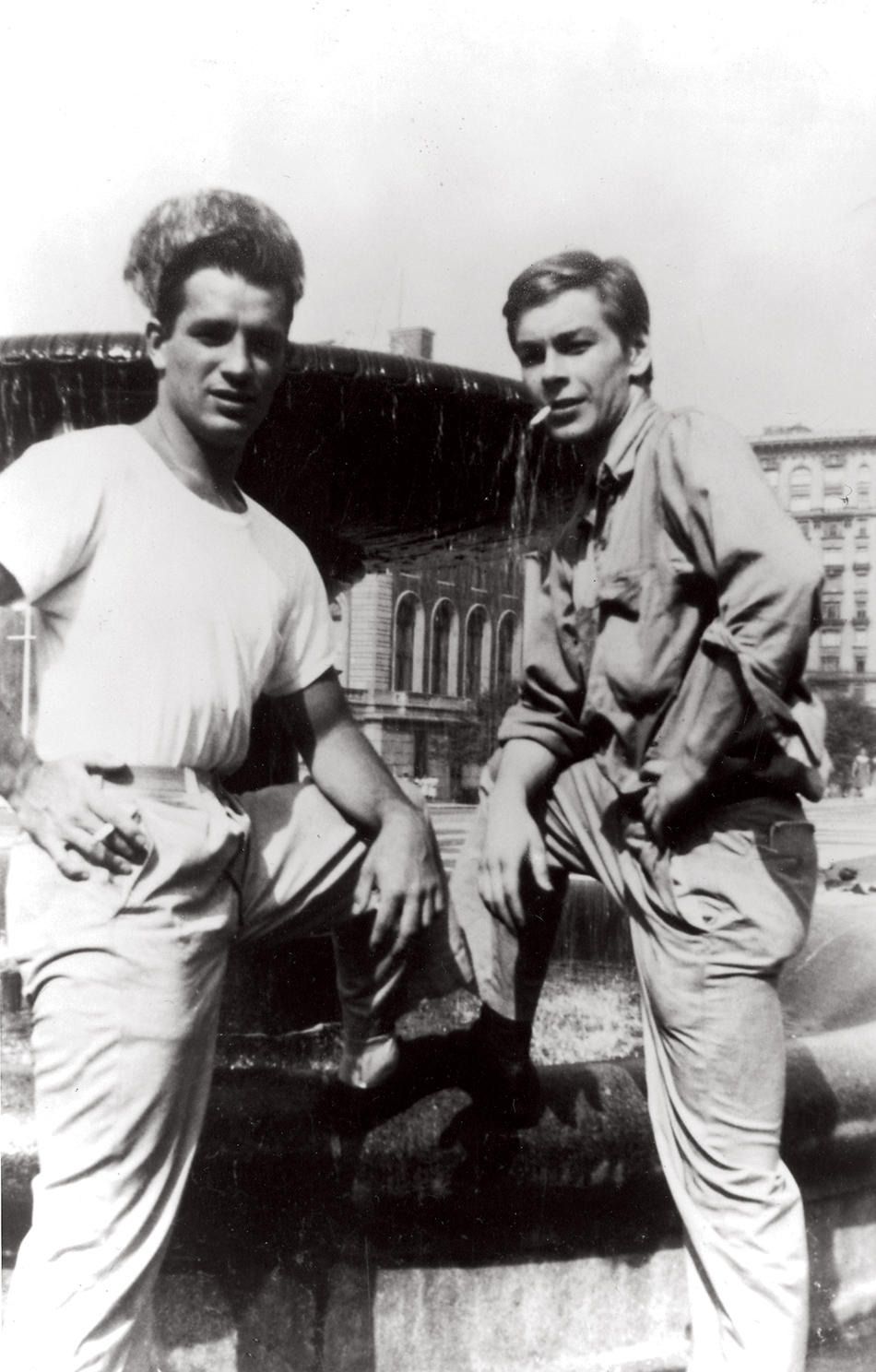

Lucien Carr was a recent transfer from the University of Chicago who seemed to attract admirers wherever he went. Uncommonly handsome, charismatic, and well-read, he was the force that initially united the group: he bonded with Ginsberg in a Columbia dorm over a shared love of Brahms, befriended Kerouac through his girlfriend at a nighttime painting class, and renewed ties with Burroughs, an old acquaintance from his hometown. Independent friendships formed between members of the quartet, but Carr was always at the center.

While his friends wrote books and became revered cultural and literary figures, ringleaders of the Beat movement, though, Carr lived most of the next sixty years in relative obscurity, quietly building a career and raising a family, and avoiding even the reflected glow from the spotlight on the others. Since his death in 2005, interest in the Beats has grown even more, at last illuminating the lost member.

This past March, Da Capo Press released Jack Kerouac’s previously unpublished first novel, The Sea Is My Brother, written when he was a twenty-year-old merchant mariner the summer before he met Carr. In April, the New York writer Aaron Latham debuted his play Birth of Beats: Murder and the Beat Generation. In September, Joyce Johnson released The Voice Is All, an intimate biography of Kerouac, with whom she had a long romance. A film adaptation of On the Road — the first, despite years of failed attempts — premiered at Cannes in May, with wide release in December. And in 2013, Carr will take center stage as the subject of Kill Your Darlings, a recent entry to the Sundance Film Festival, which was filmed largely on campus last spring and which stars Daniel Radcliffe as Allen Ginsberg.

Carr was the last of the four to die, and with all of them gone, it seems like the world is finally ready to ask two questions: Had Lucien Carr not killed a man, would he have been the greatest of what we now call the Beat Generation? And, perhaps more important, had he not killed a man, would there even have been a Beat Generation at all?

It was just after midnight when Kerouac got up from his table at the West End, where he’d been drinking with Carr, and went out into the sweltering, sleepless night. With his athletic gait, he quick-stepped across Broadway, through the 116th Street gates, up the Low Library steps, and toward Amsterdam Avenue, on his way to his girlfriend’s apartment, when he saw a familiar figure walking toward him in the dark: a tall, bearded, auburn-haired man named David Kammerer, who asked after Lucien. Kerouac directed Kammerer to the West End.

“And I watch him rush off to his death,” Kerouac later wrote in his autobiographical novel Vanity of Duluoz.

Kammerer, who was thirty-three, had known Carr years before in their native St. Louis, where he had been Carr’s scoutmaster, as well as a kind of life coach and literary beacon, recommending books that helped nurture the boy’s literary talent. But Carr was more than Kammerer’s protégé. He was his obsession. For years, Kammerer had trailed Carr to a series of schools, the latest being Columbia, where Carr, nineteen, had just completed his freshman year.

Kammerer wanted a sexual relationship with Carr, and while Carr was ostensibly straight and dating a Barnard student (which only further fueled Kammerer’s jealousy), his feelings were clearly complicated. Ginsberg later said that while Kammerer craved Carr, Carr craved the attention. James W. Grauerholz, a friend of William S. Burroughs’s and his literary executor, would describe Kammerer as Carr’s “stalker and plaything, his creator and destroyer.”

At the West End, Kammerer caught up to Carr. The two men drank until after 2:00 a.m., then headed down to Riverside Park. As they lounged on the grass at the foot of West 115th Street, Kammerer made what the New York Times would call an “offensive proposal.” Carr “rejected it indignantly,” and the men grappled. As Johnson writes in The Voice Is All, “Perhaps Lucien had never hated Kammerer more; perhaps he had never felt closer to yielding to him.”

Losing the struggle, Carr withdrew a small folding knife and twice jabbed the blade into Kammerer’s chest. As Kammerer’s life drained away, Carr rolled the body to the river’s edge, bound the limbs, weighted it with rocks, and watched his old scoutmaster sink into the Hudson. Carr was anxious to report his deed, but not to police. Instead, he headed straight to the apartments of his trusted friends — first Burroughs’s, then Kerouac’s — breaking the news with a macho, film noir–style quip: “Well, I disposed of the old man last night.”

That Carr had been at the West End at all was something of an accident: the previous day, he and Kerouac had hatched a scheme to sail as merchant mariners to Europe, where they planned a wartime visit to Paris to retrace the steps of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, a literary hero whose volatile relationship with the poet Paul Verlaine had culminated, in 1873, in Verlaine shooting Rimbaud in the arm. But Carr and Kerouac arrived at the dock too late.

Now, instead of sailing the Atlantic, they took a macabre walk through Manhattan. They stopped in Morningside Park to bury Kammerer’s eyeglasses, then went north to 125th Street in Harlem, where they ditched Carr’s old Boy Scout knife — an apt tool — down a grate. Then, delaying the inevitable, they wandered down to Midtown. The stopped at the Museum of Modern Art, ate hot dogs in Times Square, and ducked into a movie house on Sixth Avenue, where they watched Zoltán Korda’s 1939 remake of The Four Feathers, a British war adventure about cowardice and redemption.

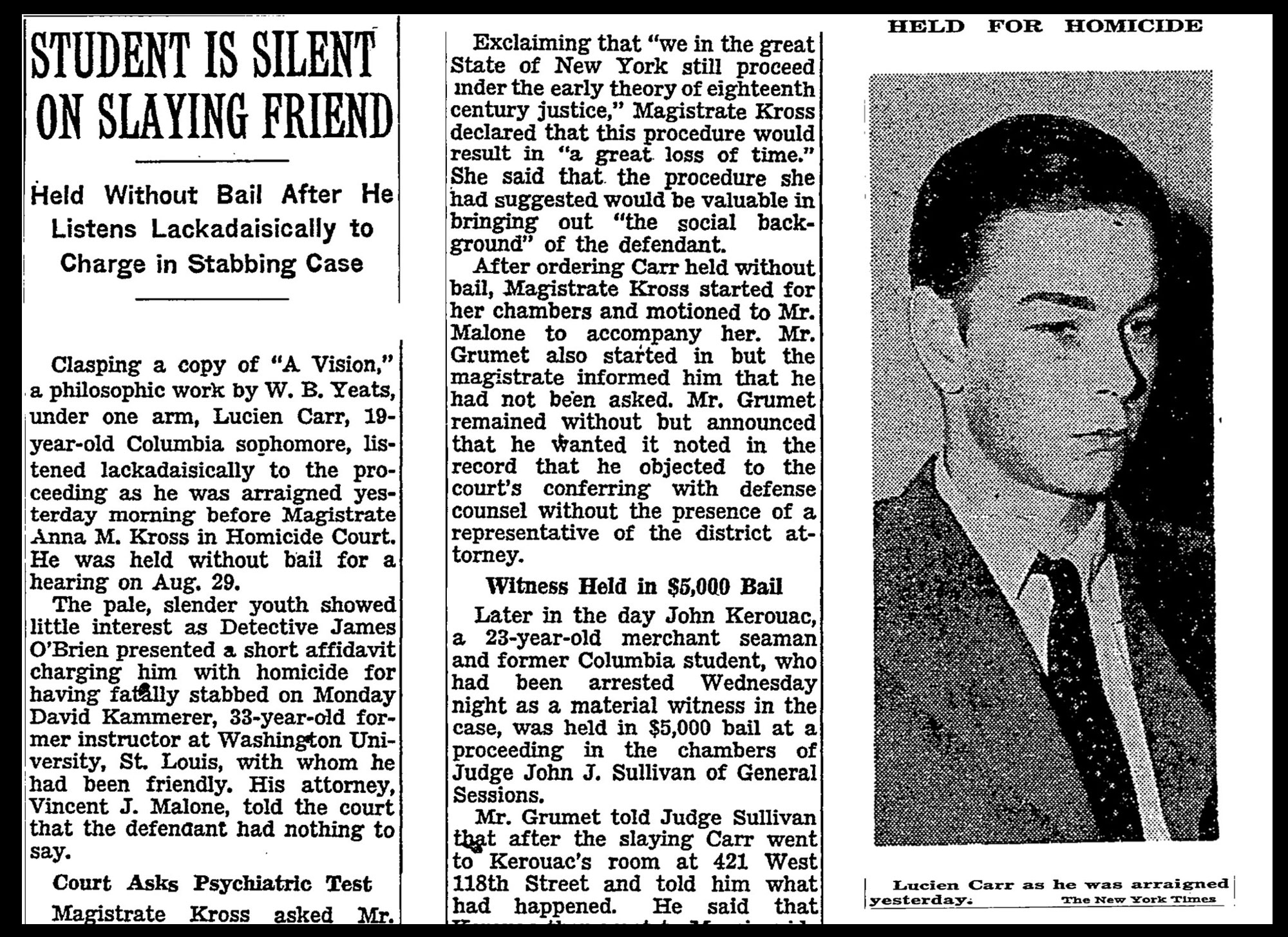

After a twelve-hour odyssey, Carr finally walked into the district attorney’s office, where he confessed. Authorities wondered whether the skinny student, who cradled a dog-eared copy of W. B. Yeats’s A Vision, was a lunatic. They doubted that he had the gumption to kill someone.

In the fashion of that era, journalists were invited to have a look at Carr as he sat in the DA’s office. They found a “slender, studious youth” who was “peacefully reading poetry,” as the New York Times put it. The Daily News called Carr “refined and erudite.” Nicholas McD. McKnight, a dean of Columbia College, spoke out for Carr, declaring him “definitely a superior student.”

A front-page account published in the Times on August 17, 1944, began, “A fantastic story of a homicide, first revealed to the authorities by the voluntary confession of a 19-year-old Columbia sophomore, was converted yesterday from a nightmarish fantasy into a horrible reality by the discovery of the bound and stabbed body of the victim in the murky waters of the Hudson River.”

“The Beats were a complicated group of people, with Lucien Carr directly at the center,” says Ann Douglas, the Parr Professor Emerita of English and Comparative Literature, who has long taught a popular course on them. “Understanding the murder, and the reasons behind it, is instrumental to understanding them.”

The day after Carr confessed, both Kerouac and Burroughs were arrested as material witnesses. Burroughs’s father came to New York to post his bail, but Kerouac’s family refused. Instead, his girlfriend Edie Parker came to his rescue, though the judge would not allow her to bail him out unless the pair married, which they did in a short ceremony on August 22, setting the course of Kerouac’s next several years.

Though Ginsberg was the only one who escaped arrest, it was on him that the murder arguably had the gravest impact. Deeply in love with Carr, he had also developed a close friendship with Kammerer and was struggling with his own homosexuality. Johnson suggests in The Voice Is All that, while Carr denied it, Ginsberg may have experimented sexually with both men before the murder. And in August, she writes, Ginsberg “spent some intensely lonely weeks mourning the loss of Lucien and ‘wonderful, perverse Kammerer,’ twice drafting suicide notes in his journal.”

The greatest change, though, was that their leader was gone. In Carr, the friends found an attractive iconoclast who harangued them with profane oratories about creativity drawn from Yeats and Rimbaud. In his journal, Ginsberg called Carr “my ideal image of virtue and awareness.” In And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, a roman à clef co-written by Kerouac and Burroughs, Burroughs describes the Carr character as “the kind of boy literary fags write sonnets to, which start out, ‘O raven-haired Grecian lad ...’” To honor Carr’s beauty, as well as his snobbishness, Ginsberg and Kerouac invented an alter ego for him, a withering French aristocrat they named Claude de Maubris.

But Carr wasn’t just the muse; rather, Johnson suggests, he was quickly becoming famous across campus as something of a literary prodigy. “His verbal brilliance impressed professors and led admirers to believe he might well become ‘another Rimbaud,’” she writes. Kerouac referred to him in Vanity of Duluoz as “Shakespeare reborn almost.” To his new friends, Carr’s intellectual prowess was as compelling as his striking good looks: it was with poetry that he wooed Ginsberg, late-night intellectual sparring that won over the often stoic Kerouac, and his precocious worldliness that lured Burroughs uptown from his Greenwich Village apartment.

“Carr was really important in getting the group together,” says Aaron Latham, who features the Kammerer slaying in his play, Birth of Beats, and who also wrote a 1976 New York magazine article about the then-forgotten case. “One key part of the Beat phenomenon was the group dynamic they had. Carr was the one friend that bridged them all.”

Or, as Ginsberg famously put it, “Lou was the glue.”

The most direct literary result of the murder was Hippos, a thinly veiled mystery novel told in alternating voices, which Burroughs and Kerouac produced almost immediately, completing a final version in 1945. They made repeated attempts to publish it over the years, though Burroughs later claimed that “it wasn’t sensational enough to make it [commercially] ... nor was it well-written or interesting enough to make it [from] a purely literary point of view.” (Near the alcohol-induced end of his own life, Kerouac readapted the material for Vanity of Duluoz.) When Grove Press eventually released Hippos in 2008, after all central parties were dead, the New York Times called it “flimsy” and “flat-footed,” noting that “the best thing about this collaboration between Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs is its gruesomely comic title.”

But the bloodshed also clearly inspired, in some senses, the tortured-soul narratives in the three elemental Beat masterpieces: Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems in 1956, Kerouac’s novel On the Road in 1957, and Burroughs’s novel Naked Lunch in 1959.

Oblique references to the event are perhaps most evident in “Howl,” which was initially dedicated to Carr. Hinting at a unity forged among the Beats through the slaying, Ginsberg wrote, “Breakthroughs! over the river! flips and crucifixions! gone down the flood! Highs! Epiphanies! Despairs! Ten years’ animal screams and suicides! Minds! New loves! Mad generation! down on the rocks of Time! / Real holy laughter in the river! They saw it all! the wild eyes! the holy yells! They bade farewell! ... Down to the river! into the street!”

Lucien Carr was charged with second-degree murder. But the sympathetic narrative of an intellectual fighting off a homosexual predator made it easy for prosecutors to offer a plea of manslaughter. A psychiatrist judged Carr “unstable but not insane,” and Judge George L. Donnellan opted to send Carr to the more genteel Elmira Reformatory rather than to Sing Sing.

“I believe this boy can be rehabilitated, and I would recommend that he have the attention of a skilled psychiatrist,” Donnellan said.

It was this narrative that, decades later, inspired Kill Your Darlings director John Krokidas to tell Carr’s story. He was initially moved by Beat literature as a gay teenager. Reading Ginsberg and Kerouac, he says in a 2009 interview, “introduced me to the idea that the idea of wanting to live outside the boundaries of society was a perfectly acceptable choice.” But ironically, he says, it was society’s rejection of that choice that spared Carr a harsher sentence. “I was furious when I discovered that in 1944 you could literally get away with murder by portraying your victim as a homosexual. They called [Kammerer’s murder] an ‘honor slaying’ or the ‘homosexual panic’ defense.”

Similarly, the Beats had mixed feelings about the academy coming to Carr’s rescue. Johnson writes that “soon Allen Ginsberg ... would be explaining to tabloid reporters the importance of the New Vision. During the pretrial hearings, Mark Van Doren and Lionel Trilling, the leading lights of Columbia’s English department, would appear as character witnesses for Lucien.” But while the portrayal of Carr as an Ivy League scholar helped garner a lenient sentence, he and his friends were constantly questioning the role of traditional education in their intellectual development. Kerouac had dropped out of Columbia, and Carr himself was ready to abandon the pending semester to join the merchant marine. After the trial, Columbia was also a convenient antagonist, says Ben Marcus, a novelist and associate professor at the School of the Arts. The young writers needed an enemy, Marcus says, and “they took a lot of energy from their subversion of the university.”

Carr spent eighteen months at Elmira, and initially, even behind bars, the haughty Count de Maubris seemed alive and well. “Lucien has changed somewhat since you last saw him due to various vicissitudes which he has undergone,” Carr, referring to himself in the third person, wrote to Ginsberg. “Still the introspective, he will never cease to see, like Thoreau, all of life in a drop of water ... And he has begun to see a little more clearly along the ascendant paths of self-consummation!”

But soon that also began to waver. Johnson writes that “the last they heard from Lucien for the next couple of years was a coded letter forwarded to Allen but addressed to ‘Cher Breton,’ in which he wrote that he was undergoing some changes in prison that were leading him to wonder whether the power of the intellect was less important than the ‘spirit.’”

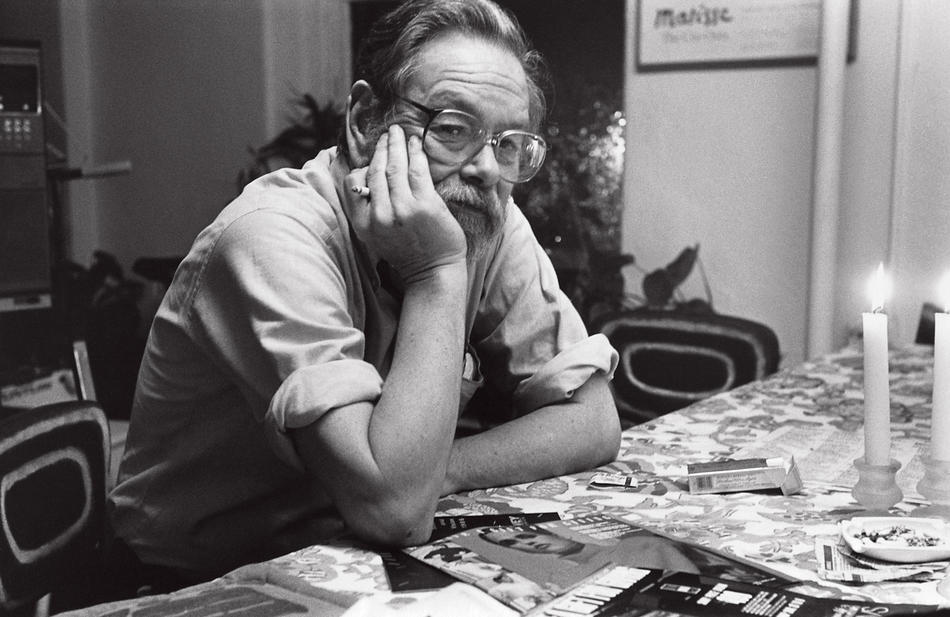

After his parole, Carr returned to New York and began a long career in a field that many would regard as the occupational opposite of brooding self-examination: he became a wire-service newsman, with United Press, which would later become United Press International.

A trove of correspondence to Carr from Ginsberg and Kerouac in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library demonstrates that although their paths diverged, they remained close friends. They chatted about everything, from world politics to Carr’s “awful” mustache. Writing from Paris in 1957, Ginsberg quoted Burroughs: “I mean, having a mustache like that to keep oneself from being pretty is like knocking out a couple of teeth or sticking in a nose-plug or some other such barbarous self-mutilation, in fact it’s worse, it’s a crime of self-desecration to try to make yourself ugly, to please a lot of jerks down at the UP & be one of the boys is terrible.”

Ginsberg added, “Jack & I agree.” The advice didn’t take hold. Carr spent much of his adult life behind a mustache and full beard — perhaps to spite his old friends. Carr distanced himself publicly from his Beat pals, initially because he feared being drawn into a parole violation by their recklessness and later because he preferred to erase the homicide from his biography. He even demanded that Ginsberg remove his name from the dedication of “Howl.”

Although Ginsberg and Kerouac occasionally visited Carr at UPI headquarters, in the Daily News Building at 220 East 42nd Street, Carr’s UPI colleagues tell me he rarely talked about his old Beat associations. Were he alive, they say, Carr would cringe at the notoriety that the upcoming film might bring.

“Lou” Carr, the UPI man, seemed to have little in common with the dreamy young Beat sage. He was a rough-hewn, tabloid-tinged editor who encouraged writers to tug at readers’ emotions. “Make ’em horny,” he would say. “Make ’em cry.” Like many journalists of that age, Carr was a heavy drinker. Unlike some, he quit before it killed him.

A 2003 history of UPI describes Carr as “the soul of the news service” who “rewrote, repaired, recast, and revived more big stories on UPI’s main newspaper circuit, the A-wire, than anyone before or after him.”

When UPI moved its headquarters from New York to Washington, DC, in 1982, Carr moved, too — from a loft apartment in SoHo to a boat moored in the Potomac. He died of complications from bone cancer in 2005.

Carr’s former UPI colleague Wilborn Hampton crafted an apt epitaph in a Times obituary. He called Carr, the former freethinking Columbia freshman, “a literary lion who never roared.”