A white refrigerator bobbed below my open window and caught in the tree’s branches. I rubbed sleep from my eyes and gazed at the brown river 15 feet below. The river, which hadn’t been there the night before, flowed between my apartment complex and the townhouse across the causeway. The clock read 5:30 — time for the birds’ chorus and the outbreak of brilliant, hot sunshine that made me wish I was a morning person. But the magpie and kookaburra had not woken me today. An endless siren pierced their songs.

The smell of cooked kangaroo and tomatoes hit my nostrils when I opened my bedroom door. Tigue was making his famously pungent chili in the kitchen. He saw my quizzical look and said, “Electricity is being shut off at eight. Thought we should empty the fridge, have a good meal.” I wondered if our neighbors had done the same before theirs was swept away.

I wandered out to the balcony, where our third roommate, Dave, was grilling sausages. I saw that our swimming pool, swollen at bedtime the night before, had engulfed the entire courtyard. “Who knows how to swim?” said Tigue. He had survived the 2004 tsunami in his native Sri Lanka, so our current flood in Brisbane, the worst natural disaster Australia had ever seen, barely made him sweat. I raised my hand, recalling the morning of my college graduation five years earlier, when I reluctantly dove into the crisp Columbia University pool to fulfill my undergrad requirement. There is a running joke that Columbia College students are required to take a swim test so that, should catastrophe strike Manhattan, they could swim to New Jersey.

“There is no way I am swimming in this water,” I announced to the six classmates holed up in our second-story flat. I could handle the toxins of the Hudson, but the muddy lake pooling around us posed a legitimate threat from bull sharks and the most poisonous snakes in the world. We live in a modern city of three million people but keep a Field Guide to Australian Reptiles on our coffee table.

Tigue likes snakes. After breakfast, he and Dave, both well over six feet tall, went on a mission to survey the neighborhood, help where they could, and salvage supplies, wading up to their necks through the courtyard. “Come back with a boat!” I shouted.

Twenty-four hours earlier, on Tuesday, January 11, I had returned from visiting my family in snowy Manhattan to begin my second year of medical school as part of an international exchange program between Ochsner Clinical School in New Orleans and the University of Queensland School of Medicine in Brisbane, Australia. When I landed, the pilot announced, “Welcome to Queensland, the Sunshine State!” It was raining. News of flooding far north of Brisbane had reached me during the break, but I had noticed over the previous year that the country was in constant flux between rain and drought, flood and fire. I figured it was business as usual.

It wasn’t. The rains had begun in December and traveled over three-quarters of the vast state of Queensland, inundating one town after the next. Canals overflowed south into the bloated Wivenhoe Dam, and subsequent runoff into the Brisbane River broke its banks late on the day I arrived. David Wilkinson ’65PS, who is dean of the University of Queensland School of Medicine, later wrote to me, “Initially [the flood] was something that affected other people in other places, far away. Then friends started to be affected, and then teaching sites began to be cut off. As Rockhampton [the site of one of our teaching hospitals] became isolated, it all became far too real.”

Now I stood on the balcony and snapped a photo with my iPhone of the floating lawn chairs that had joined the refrigerator. I uploaded it to Facebook, and within minutes I received messages from former Columbia classmates living in Thailand, California, and Sydney, offering refuge. Theo Borgovan ’08GSAS, my classmate in the Ochsner program, called to say that he and his wife were on high ground about two miles away and could provide electricity, food, and a couch.

An emergency service rescuer paddling a tinny stopped by to check on us. He applauded our stockpile of Brisbane’s local beer, XXXX (pronounced “four-x”). I didn’t mention that we only had one rose-scented candle and three medical “say ah” flashlights for the impending powerless night. He declined to join in a toast, but informed us that the brewery had flooded. Cans and kegs were floating down the main drag. He advised us to stow our belongings as high as possible and to take any valuables with us. “But it’s just stuff,” I heard countless times in the following days, from people who had much more to lose than I did.

People near us fled to higher ground by Jet Ski, kayak, and blow-up raft. It was exciting being in the midst of the flood action, boldly stating that we’d only evacuate if it were via the helicopters that flew overhead. But the humor only masked our knowledge that others had it far worse. Toowoomba, a town that I’d visited on a rural hospital trip, had not had the warning and gradual flooding afforded to Brisbane, but instead had been struck by what news stations called an “inland tsunami.” Television channels played the same images of families trapped on vehicle roofs, captainless boats running into bridges, water swallowing up homes, and loved ones missing.

I measured time not in minutes or hours, but by the steadily disappearing railings and staircases of our building, counting the number of steps the water had to go before it reached us. As a sophomore, I had survived torrential rains on a spring break trip to Florida with the Columbia sailing team. I could handle this. Yet despite my self-confidence and trustworthy friends, it was hard not to cry. The rapidly changing scenery made me feel both awe and uncertainty.

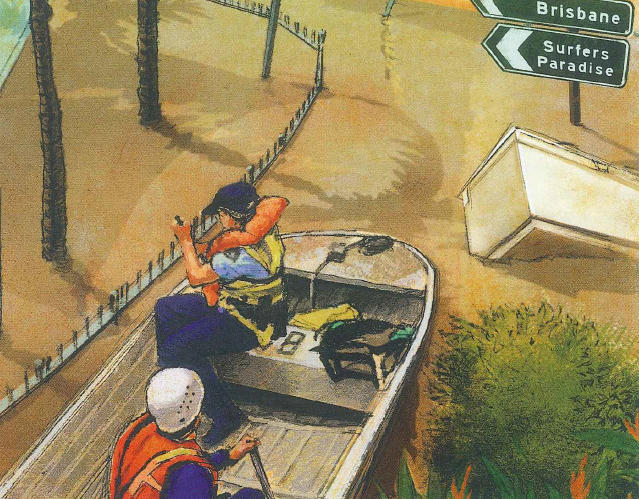

Dave and Tigue paddled up to our balcony in a tin motorboat borrowed from the flooded University of Queensland boathouse. I laughed with relief. The rising waters had seeped into the flat below ours, and it was past time to evacuate. We received a text message from our clinical skills professor: “Situation will worsen. Land Rover at your disposal. Come over now!”

We navigated our boat through garbage, over fences we knew to be just below the murky surface, and emerged onto a vast lake that covered the road and cricket pitch underneath. I stared in shock at the tips of signs marking Nando’s Chicken, the corner store, and the bakery. We followed the treetops that indicated the road heading uphill. When we reached dry land, we docked the boat and joined our neighbors registering with emergency service workers.

We spent the next two days at a friend’s crowded flat in hungry, muggy idleness. Power was out. The 90-plus-degree summer heat intensified the odors of mildew and sewage. Grocery-store shelves were bare from the previous days’ scramble to stock up on bread, milk, and bottled water. Tigue miraculously scrounged up a bag of oranges to supplement our crackers and canned tuna.

School was canceled. We were still responsible for the week’s material but could not take advantage of the free study time without access to the Internet or study materials. Frustration merged with helplessness as we waited for the flood to run its course through Brisbane. After reaching its peak of 14.6 feet on January 13, the water steadily receded, revealing a thick carpet of putrid brown sludge.

Day one of the cleanup effort brought 12,000 registered volunteers to Brisbane, with three times as many flood victims, friends, and strangers walking the streets with buckets. People accepted what had happened and began cleaning. All we had to do was shout into someone’s home, “Do you want a hand?” I watched a little boy pretend to fly his mop down the driveway. He wrung it out and brought it back again to his father.

Tricia, Dave’s girlfriend visiting from the United States, chose to stay in Brisbane to help for the week rather than return home or flee to the beach. Women and children showed up with water, sandwiches, tea, and coffee. Tigue joined two Australian defense squads at the end of our street loading heaps of rubbish into trucks. “Military or civilian,” he later said, “it didn’t matter who you were, what the job was, it got done. With smiles! No one complained.” Strangers cleaning apartments in our complex joked, “How do international students have so much stuff?”

Our swimming pool was a mud pit; the flowers and bushes were gone. Luckily, the water crested 13 steps below our door — our textbooks were spared. Armed with boxes of tea candles, Dave and Tigue chose to live in our powerless flat. I escaped to the spare bedroom of a generous classmate who had not been affected by the flood.

I cranked up her air conditioner and swam in her clear pool, while Dave and Tigue took cold showers and heated the kettle for morning coffee on the propane grill outside. When the electricity was restored two weeks later, I returned to the flat, scrubbed it from floor to ceiling (our shoes had tracked mud everywhere), wrapped up the vacuum cord, and eagerly dove into my freshly made bed.

The following morning I woke to the birds’ songs. I opened my blinds and saw a large University of Queensland research speedboat still nestled in the center of the cricket pitch.