In the days leading up to the seminar, Robert Pollack ’61CC wrestled with his chosen text. Pollack’s credentials are impeccable: a biology professor and dean of Columbia College from 1982 to 1989, he is a former Guggenheim Fellow and recipient of the Alexander Hamilton Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the Columbia College Alumni Association. Yet still he fretted. In a matter of days, twenty people — scientists, writers, educators, artists — would convene on Zoom to discuss I and Thou, by the German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. The book is a short, aphoristic, notoriously opaque work, and Pollack, who with Peter Gruenberger ’58CC, ’61LAW is co-chair of a University Seminar called Science and Subjectivity, hoped it wouldn’t be too off-putting.

The word “seminar” may rouse images of a circle of students and a professor, but the University Seminars are a different beast: a network of thinkers who convene regularly during the academic year to discuss issues of perennial concern. They gather not in classrooms but in the meeting rooms and dining rooms of Faculty House (currently they meet virtually), where they hold democratic, freewheeling, civil, sometimes excited, and always revelatory conversations about everything from American studies to Zoroastrianism. Members include not just the faculty of Columbia and other universities but also public officials, businesspeople, and labor leaders, as well as historians, doctors, linguists, painters, and poets.

At seventy-five, the seminars are a thriving institution with a remarkable tradition of intellectual ferment. Pollack’s seminar is just one of ninety-two groups engaged in constructive, creative dialogue. “The principle of the University Seminars is the honest but non-hostile exchange of views on a topic which may be tendentious and troubling or just interesting and difficult,” says Pollack, who started his seminar in 2018 and directed the program from 2011 to 2019.

The avenues of interrogation are implicit in the seminars’ names: Language and Cognition, Memory and Slavery, Energy Ethics, Ecology and Culture, Religion in America, Economic History, Women and Society. Usually lasting ninety minutes, seminars are closed to the public and press (thus their low profile) and, to further ensure academic liberty, are autonomous from the central administration. A paid graduate student, called a rapporteur, takes minutes of the meetings, which may be kept under seal for five years at the choice of seminar members before being archived in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. There is no audience for the sessions, no remuneration, no academic credit, no acclaim. What the program does offer is a chance for participants to take intellectual risks without fear of judgment — and to encounter new ideas.

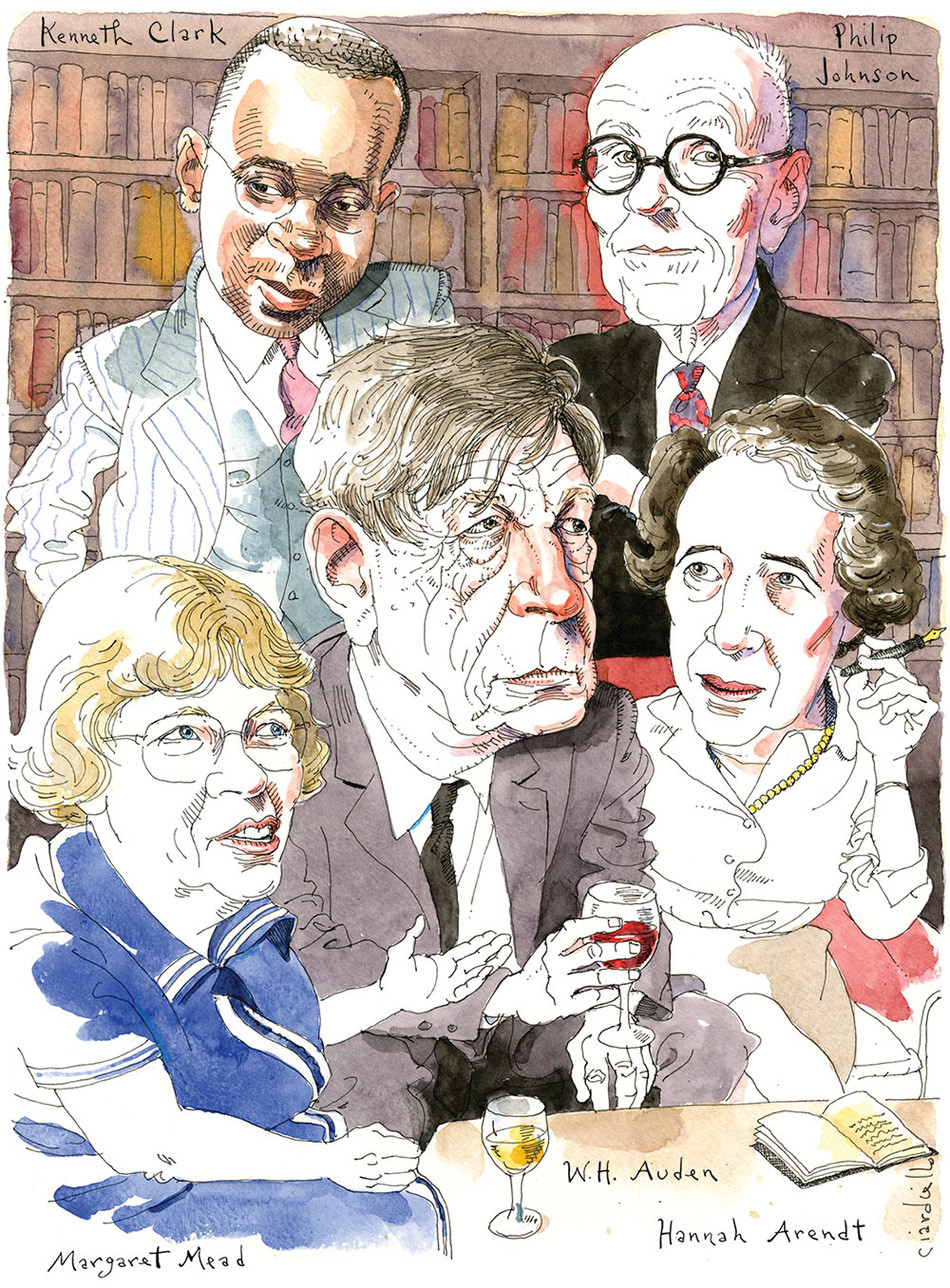

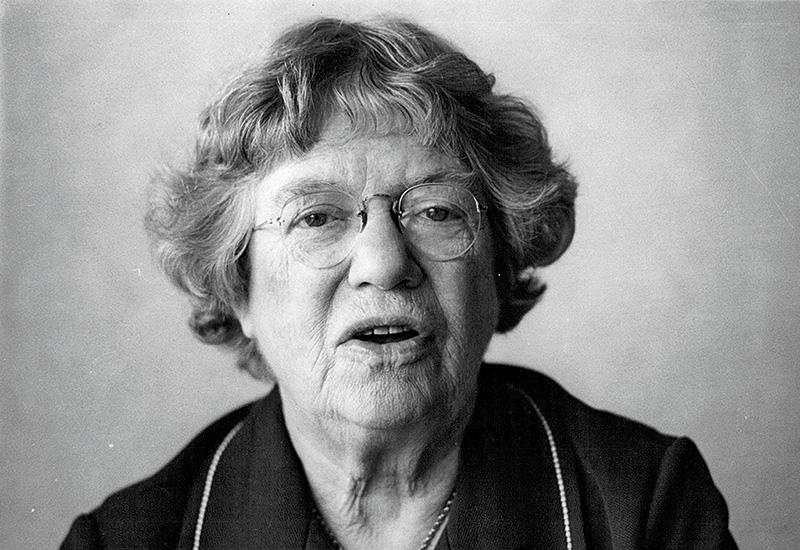

The lure of that opportunity is reflected in the roster of University Seminars members over the decades. Columbia professors like historian Richard Hofstadter ’42GSAS, anthropologist Margaret Mead ’28GSAS, ’64HON, Nobel-winning physicist I. I. Rabi ’27GSAS, and jurist Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59LAW, ’94HON, as well as guest speakers like poet W. H. Auden and political philosopher Hannah Arendt, all joined the seminars to challenge themselves and each other. That dynamic continues today, furthering with every spirited roundtable what Pollack calls “an ongoing experiment in continuity and novelty.”

In 1944, with the world at war, professor of Latin American history Frank Tannenbaum 1921CC and eighteen other humanities professors approached acting president Frank D. Fackenthal, who had just replaced the retired Nicholas Murray Butler. The professors wanted to start a program that would break down the walls of academic specialization and combine the brainpower of the University to tackle subjects beyond the limits of any one discipline. Fackenthal approved the initiative.

Tannenbaum was an unlikely figure to start a pedagogical revolution. Born in 1893 in a shtetl in Galicia (in what is now western Ukraine), he immigrated to rural Massachusetts with his family and at age thirteen ran off to New York, where he worked menial jobs (busboy, elevator operator) and got involved in labor politics. In 1914, as a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, he was arrested for his role in leading protests on behalf of unemployed laborers and spent a year in prison. On the strength of recommendations from influential patrons who had followed his trial, Tannenbaum, who never finished high school, was admitted to Columbia College in 1916 at age twenty-three. He graduated with honors, and after writing a landmark book on penology, he worked as a journalist in Mexico and later got his PhD in Latin American history before returning to Columbia in 1934 as a professor.

In 1945, Tannenbaum launched the University Seminars with five broad subjects: The State, Rural Life, Studies in Religion, The Renaissance, and The Problem of Peace. Believing that academic specialization hindered the University’s potential as an incubator of solutions to multifaceted problems, Tannenbaum sought, as he once stated, “to reassemble specialists so that they can see the whole again.” This standard could only be achieved in a state of pure independence: “The group must feel completely free to follow its own bent, it must be responsible only to its own academic conscience, and it must be untrammeled in organization, method, and membership.”

“Tannenbaum’s extraordinary invention was to ensure that if you wanted to place the importance of ideas before your reputation, the University would create a forum for that to happen,” Pollack says. “That’s so important.”

By the 1950s, the program had taken off. The decade saw twenty new seminars, including American Studies, Medieval Studies, and Studies in Contemporary Africa, all of which are ongoing. (The lifespans of the seminars, like their styles and subject matter, vary.) The 1960s brought further expansion, with the addition of offerings like The City (1962), which presented such diverse speakers as architect Philip Johnson, psychologist Kenneth Clark ’40GSAS, ’70HON, and police captain Carl Ravens of the 26th Precinct. The seminar on The Nature of Man (1968), which was chaired by Mead, comprised an equally eclectic group that included mathematician Richard Courant, political scientist Hans Morgenthau, and Columbia historian Morton Smith. One session featured a rollicking, erudite address by Auden, who riffed on Darwinism, Carnival, and the hippies while dropping Latin phrases and pouring himself glass after glass of wine. [Read the full transcript of the seminar.]

In 1982, the program inaugurated what is now the largest seminar, Shakespeare, which has fifty members. And in 1998, Chauncey G. Olinger Jr. ’71GSAS, who was Mead’s rapporteur while getting his master’s in philosophy, started a seminar with Barnard historian Robert McCaughey on the history of Columbia. That seminar has delved into the University Senate and the Core Curriculum and devoted a full year to discussion of the campus upheaval of 1968. For Olinger, who was a student and friend of Tannenbaum’s, the University Seminars “were an invention as significant as the Core Curriculum.”

More than fifty new seminars have emerged in the twenty-first century, and today the program involves some three thousand people. Anyone wishing to join a group must e-mail the chair (find more information at universityseminars.columbia.edu) and may attend meetings as a guest with the option of applying for membership. “We’re always trying to bring in younger faculty,” says Alice Newton ’08SIPA, the longtime assistant director of the University Seminars who is currently the interim director. “One of the great advantages of joining a seminar is that you come with something you’re working on, a topic that everybody knows, and you get input.”

Newton calls the University Seminars “a holistic method of looking at problems,” leading to “new types of collaborations.” This ideal is well illustrated in the seminar on Death, which attracts philosophers, ethicists, nurses, psychologists, architects, and anthropologists who grapple with issues of aging and quality of life, cultural attitudes, suicide, and the disposal of corpses. The chair, Christina Staudt ’01GSAS, earned her PhD in art history (she focused on images of death), was cofounder and president for fifteen years of the Westchester End-of-Life Coalition, and has been a hospice volunteer for over twenty years. “How we treat the dying and the dead has always been an indication of the values of the culture at large,” she says. “One of the main intentions in the seminar is to make people more aware of their mortality and to live accordingly.”

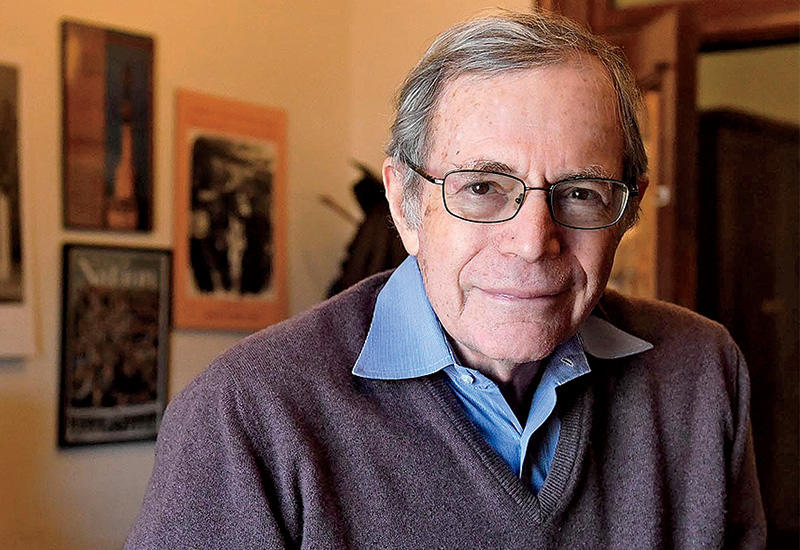

The seminars, of course, are more than ephemeral conversations. In 2005, Robert Belknap ’57SIPA, ’59GSAS, a renowned professor of Russian literature and director of the University Seminars from 2001 to 2011, started a project to digitize half a million pages of typed, carbon-copied, and sometimes handwritten transcripts, summaries, and notes in order to create an intellectual history of the seminars. The program also boasts more than four hundred books that were influenced by participation in a seminar. Among them are the Holocaust study Desolation and Enlightenment, by Columbia interim provost Ira Katznelson ’66CC; The Encyclopedia of New York City, edited by history professor Kenneth T. Jackson; Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England, by Sharon Marcus, professor of English and comparative literature; Globalization Challenged, by former University president George Rupp ’93HON; and Pollack’s The Faith of Biology and the Biology of Faith.

Upon his death in 1969, Tannenbaum, with his wife, Jane Belo, an anthropologist and daughter of a Dallas newspaper magnate, left $1.5 million for the University Seminars, an endowment that has grown over the years to meet the program’s needs. These funds cover administrative costs and events as well as travel and lodging for guest speakers, meals at Faculty House, salaries for graduate-student rapporteurs, and conference funding. And the Leonard Hastings Schoff and Suzanne Levick Schoff Memorial Fund supports seminar-based books published by Columbia University Press.

One of those books, A Community of Scholars, was released this past November in honor of the University Seminars’ seventy-fifth anniversary. A volume of thirteen essays edited by Thomas Vinciguerra ’85CC, ’86JRN, ’90GSAS, with prefaces by Newton and Pollack, the book examines individual seminars through the eyes of their chairs and members, offering a rich sampling of the program’s range.

“The University Seminars, in many respects, represent the very essence of Columbia’s intellectual community,” says University President Lee C. Bollinger. “I could not be more proud to share my regard and appreciation for this program, which offers the stability of tradition while providing ample space for the novel and inventive.”

The “novel and inventive” can arise at any moment, in any number of ways. As Pollack deftly steered the Science and Subjectivity cohort in a discussion of Buber’s I and Thou, the participants on Zoom offered observations, interpretations, and questions. Published in 1923, I and Thou is all about subjectivity, or rather, intersubjectivity, a philosophical term denoting the shared experience of two minds. It argues that human relationships come in two categories: the I–It (transactional, exploitative, limited) and the I–Thou (intimate, transparent, boundless); and that only through the latter — person-to-person encounters that spark an ineffable connection — do we fully realize our humanity and glimpse the divine.

Pollack expected mixed reviews, and he got them. Some rebuked the book’s opacity and stated unapologetically that they didn’t understand a thing.

And then Ray Lee chimed in. Lee, a senior research scientist at the Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute at Columbia, developed the world’s first dual brain scanner — an MRI for two — and studies what happens to the brains of two people who interact. Buber’s notion that the I–Thou encounter creates a new spiritual sphere gave Lee a shock of recognition: his MRI experiments showed that when two people communicate, new neural pathways light up: a kind of physical affirmation of Buber’s thesis. In his reading of I and Thou, Lee saw his data explained in mystical terms.

Lee’s articulation of this thunderbolt sent a palpable charge through the faces arrayed on the Zoom screen. When asked about it afterward, Pollack gave perhaps the definitive summation of the University Seminars.

“That thunderbolt,” he said, “struck a very fertile garden. But the real point here is not the thunderbolt; it’s that the garden is there for it to strike.”

This article appears in the Winter 2020-21 print issue of Columbia Magazine with the title "Let There Be Light."