As Columbia prepares for the fusillade of remembrances that will accompany next year’s fiftieth anniversary of the campus uprising of 1968, the University Seminars have gotten a head start on the latest round of ’68 soul-searching. Since their inception in 1944, the seminars have presented intellectual offerings in some ninety subjects, including peace, death, the New Testament, comparative philosophy, and the history of Alma Mater itself. The first seminar this past academic year centered on David B. Truman, the former Columbia College dean and University provost whose career was upended by the turmoil of 1968.

The speaker was Truman’s son, Ted, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, DC. Before two dozen guests in Faculty House, Truman fils discussed Reflections on the Columbia Disorders of 1968, a memoir his father had long agonized over after leaving Columbia in 1969 to become president of Mount Holyoke College. The work remained sealed in the Columbia archives until David Truman’s death in 2003. It was published in 2009.

An energetic and personable political scientist, David Truman joined the Columbia faculty in 1951. In 1962 he became dean and quickly won undergraduate praise, in part for affirming the College’s centrality to the University. Elevated to provost in 1967, he was poised to become president.

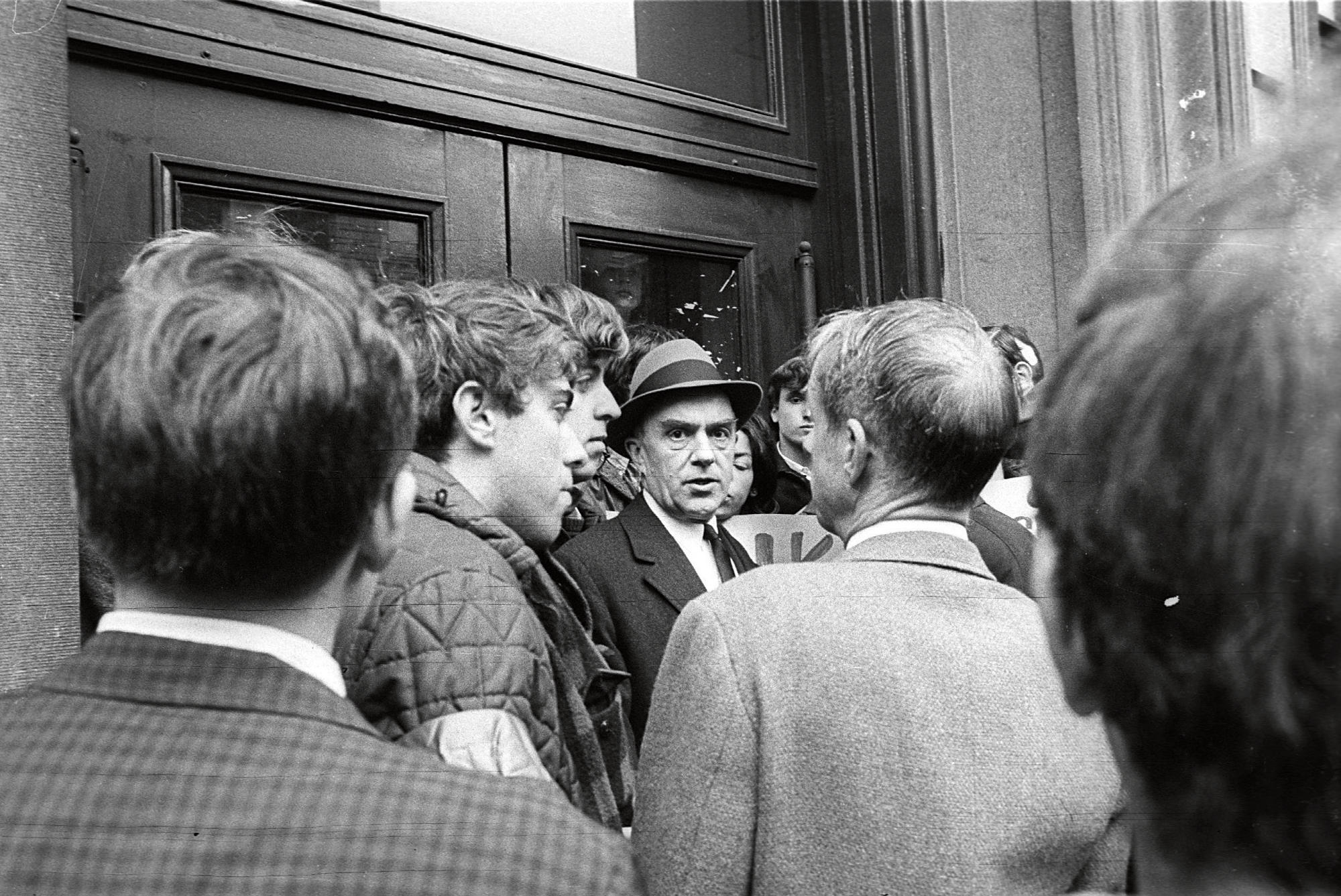

But in April 1968, students and administrators clashed over the University’s plan to build a gymnasium in Morningside Park and over its ties to the Institute for Defense Analyses, a weapons-research think tank. Students seized five campus buildings and demanded amnesty as a precondition for negotiations. Truman balked, and in the end, the administration called in the NYPD — an action that resulted in the beatings of students and some seven hundred arrests. Rightly or wrongly, “the bust” cast Truman as the authoritarian voice of Low Library.

“He loved Columbia,” said Ted Truman, wearing a dark-blue tie adorned with a light-blue Columbia crown motif. “As far as I knew, he was not bitter, just disappointed. But he suffered from acute depression afterward.” That, combined with his Mount Holyoke duties, delayed Truman père from putting down his thoughts at length. Finally, Ted and his wife gave David a computer for his fiftieth wedding anniversary, which facilitated the catharsis.

“My depression came from the nightmarish experience of witnessing, of experiencing, what can properly be described as the disintegration of a great university,” the former provost wrote.

The University Seminars are closed to the public and the press “to encourage candor in discussion of controversial issues,” as the website notes. What can be said is that on this evening, Truman and ’68 were vigorously discussed. The conversation continued at a post-seminar dinner.

“I think David did the best he could, and I don’t think anyone could have done better,” said Michael Garrett ’66CC, ’69LAW, ’70BUS, who as a student leader got to know Truman well. “He was so frustrated with the naiveté and silliness of the faculty, and so shocked that the students could be manipulated so easily by the radicals, and so disappointed by the cops and members of the administration and Trustees. He was in an impossible situation from day one.”

An especially sore point was Truman’s relations with the Ad Hoc Faculty Group, which posited itself as an intermediary between the students and the administration. “He felt the group did not realize that the goal of the hard-core radicals was to bring down the University and start the revolution,” said Ted Truman.

“When Ted’s father claimed that it was the objective of the radical students to destroy the University,” countered Fayerweather occupier Frank Kehl ’81GSAS, ’81SIPA, “he was not being a political scientist but a participant observer who had a stake in an outcome that was positive for the Trustees and the administration, and was seeking allies.”

Ted Truman dismissed that notion. “My father said, ‘We’ll have to call the cops, and I’ll have to resign.’ So he had no reason to seek allies.” As David Truman wrote, “I still regret that it was necessary to involve police in the Columbia crisis ... But I do not see, even after more than twenty years of continual and, I guess, inescapable reflection on those events, any reasonable alternative that in the circumstances was available to us.”

This is how Truman concludes his Reflections: “Behind this Columbia story another can be told, although I probably shall not write it. That story is implicit in much that I have written in these pages. It has to do with friendships, colleagueships, that I treasure. It has to do with the pride that I felt in joining the Columbia faculty and in being one of a group of scholars of standing and substance with whom it was an inspiration to be associated ... It is a better story.”

“He labored over each word,” said Ted.