It was a warm Saturday afternoon, May 19, 1923, and the Columbia Lions were playing the Wesleyan University Methodists and hoping for their fourth consecutive victory. With a record of 8–7, the Lions had been struggling to play winning baseball, despite the efforts of their star first baseman, outfielder, and pitcher, Henry Louis “Lou” Gehrig.

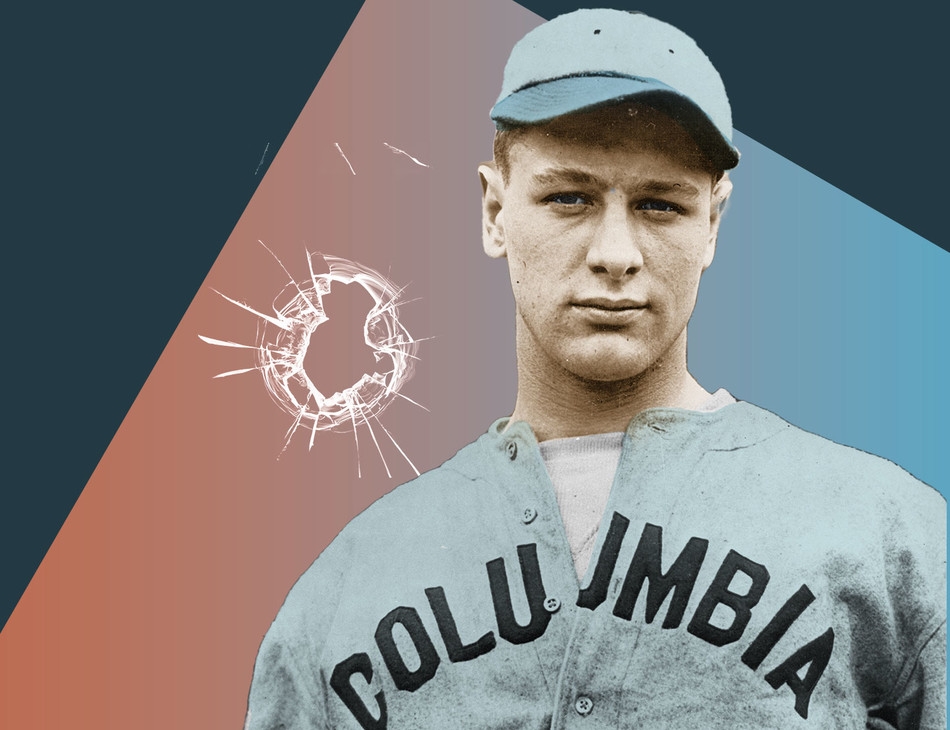

Gehrig was a multitalented athlete. The recipient of a football scholarship at Columbia, he had been forced to serve a year’s suspension from all collegiate sports for playing professionally for the Hartford Senators under the nom de guerre Lou Lewis during the 1921 baseball season. As a result, Gehrig was first eligible to suit up on the gridiron in the fall of 1922, and 1923 was the only year he would play baseball for the Lions.

He made the most of it, carrying a .516 batting average into the Wesleyan game. Like Yankees slugger Babe Ruth, who had been a lights-out pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, Gehrig was a fearsome hitter as well as a dominant southpaw. Just a month earlier, on April 18 against Williams, he had struck out a club record seventeen batters. But in the May 19 game, while he gave up just three hits to Wesleyan in a 15–2 Lions romp, Gehrig would make his biggest impression at the plate.

In the first inning, leadoff hitter and freshman second baseman Charlie Kennedy singled to center. With one out, the sophomore hurler Gehrig strode to the plate. Clad in gray flannels with navy-blue Columbia lettering on the front, Gehrig stepped into the left-handed batter’s box, clutched his lumber, and fixed his gaze on pitcher Joseph Layton “Layt” Moore.

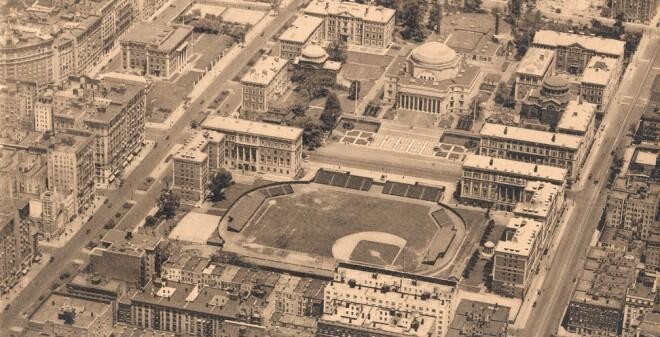

South Field, just north of 114th Street on the Morningside Heights campus, was at the southernmost edge of the growing university, and from home plate Gehrig could see Low Library beyond the right-field bleachers and, behind center, the brick-and-limestone marvel of the School of Journalism, more than four hundred feet away. A week before, Gehrig had launched a ball over the stands into 116th Street, which would later become College Walk.

Now Kennedy took his lead off first, and Moore hurled the baseball toward home plate. Gehrig stepped forward and unleashed his mighty swing.

What happened next has been a matter of speculation for a century. The 1942 Gehrig biopic The Pride of the Yankees (cowritten by Herman Mankiewicz 1917CC) depicts “Columbia Lou” hitting a blast so prodigious that it broke a window beyond center field — exactly where the journalism building stood. But did the homer actually shatter glass in the edifice that is known today as Pulitzer Hall?

Contemporary accounts of Gehrig’s clout differ. The Columbia Daily Spectator wrote that the ball “bounded in front of Journalism.” The Hartford Daily Courant, which serves Wesleyan territory, reported that “the sphere went over the center field stands and hit the School of Journalism building.” The New York Times offered a third account, stating that the ball sailed “into the small campus surrounding the School of Journalism building.”

So unless three reporters from three different newspapers somehow missed it, there was no broken glass that day.

The Lions finished the 1923 season 10–8–1. By then, Gehrig had signed with the Yankees, and on June 15, just shy of his twentieth birthday, Gehrig made his debut in pinstripes as a ninth-inning replacement at first base. Two years later, on June 1, 1925, he entered a game as a pinch hitter, which marked the beginning of his fabled streak of 2,130 consecutive games played. The feat ended on May 2, 1939, when Gehrig, ailing with what would be diagnosed as ALS, removed himself from the lineup. His record of durability stood for fifty-six years.

Today, long after Gehrig’s storied career as baseball’s Iron Horse, the legend of the shattered glass at Columbia still swirls.

“What I’ll never also forget are those stories that they used to tell about how Lou broke all of those windows in the journalism building with his home runs,” recalled the late Gene Sosin ’41CC, ’58GSAS, who was a director of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, upon the seventieth anniversary of Gehrig’s death in 2011. “Myths, perhaps. But good myths.”