On October 19, 1991, Al Mercado got a call at his home in Oakland, California, from Howard Greenberg, a New York gallery owner who specializes in photography. Greenberg was preparing a show on the Photo League of the 1930s and '40s and knew that Mercado had been a member just after World War II.

"Greenberg had seen my stuff," says Mercado '49GSAPP. "He said he'd like to come over the next day to look at some pictures."

The next morning, after setting aside a dozen vintage prints for Greenberg to consider that afternoon, Mercado and his girlfriend stepped outside and were startled to see smoke and flames rising over the surrounding hills. "By 11 o'clock we knew we had to get out," he says, and they hurriedly loaded his car with valuables. "But the fire was moving so fast, my girlfriend started crying that we shouldn't take the car, that it would be safer to walk down the hill. So I grabbed one book of negatives from the car and we started out on foot. On the way down, we saw deer with their fur singed and smoking from the fire."

The Oakland Hills firestorm had begun the previous night when vagrants set a small fire, which the local fire department thought it had extinguished. But it wasn't out, and strong winds ignited a wild blaze that would kill 25 people, leave 5000 homeless, and destroy or damage 3500 homes and apartments.

"When we got back to the house a couple of days later, there was nothing left," says Mercado. "Nothing." No house, and not a trace of his 60-odd years of photography. "Thousands of color slides, all my prints, and hundreds of black-and-white negatives were destroyed."

The one batch of negatives he carried out hints at the loss. But those surviving images are gems.

Street Smart

Alfred Mercado was born outside London in 1922 and immigrated as a young child to Brooklyn with his family. "I grew up in a slum area in the middle of the Depression," he says, "and I really knew New York's streets."

Mercado started taking pictures when he was in his early teens, using an odd camera called the Univex Mercury. The Univex was a half-frame camera, which means that it exposed two images in the space of a regular 35mm frame. It was complicated to operate, but smaller than the cameras that most people were using at the time, and one that got twice as many pictures from a roll of film.

Mercado graduated from Brooklyn Polytechnic in 1944 with a degree in civil engineering and was drafted not long thereafter. He was shipped to England in early 1945 with the Army Corps of Engineers just as the war in Europe was winding down, and later transferred to Liège, Belgium. "The army didn't know what the hell to do with us," he says. "They were waiting to invade Japan."

While they were waiting, Mercado took a lot of photographs - and his cameras kept getting better. "In the army, people were always trading things. I picked up a revolver and traded it for a Rolleicord or a Rolleiflex. I asked an old German prisoner to make me a leather case for it and he said he would if I could pay him in cigarettes."

In the summer of 1945, Mercado had Army business to attend to in Frankfurt, so he drove a jeep the roughly 200 miles from his base. He rolled alongside the river Main and entered Frankfurt, then pulled up in front of the railway station. "I looked across the city and hardly saw a building standing," he says. "There was nothing between the station and the I. G. Farben building a mile or so away, where Eisenhower had his headquarters. I felt I was looking at all the destruction in Europe. I wanted to rebuild the world."

Major League

Mercado returned to New York in 1946 and began studying photography more seriously, first at the New School and then with Sid Grossman's Photo League. The League had been established in 1936 as a kind of leftist cooperative and school for socially responsible photography, and some of the most important photographers of the day were affiliated with it, including Ansel Adams, Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, Helen Levitt, Sol Libsohn, and Weegee.

"It was all very informal," says Mercado. "We'd meet in Grossman's tenement apartment in the Village, where his bathroom was his darkroom. There were five or six students and every week we had to bring in a bunch of contact prints for Grossman to criticize. He was quite a criticizer, and we didn't like each other. I thought he was an overbearing son of a bitch and I told him so. But even if I never followed his specific directions, I did learn from him. We were both street photographers, so he had his students do a lot of walking in the streets.

The League was targeted as a Communist-backed organization in the late 1940s. "I was told to get out," Mercado says. "Otherwise, I'd be hurt for life. The FBI called me about a friend, but you didn't say anything to anybody. It was a very bad time for artists." The League was shut down in 1952.

There were factors beyond the blacklist that pushed Mercado away from photography as a profession. "Very few people make it in photography," he explains. "Either you starve or you teach." Still thinking about the destruction he had seen in Europe, he decided to make his living in city planning, so he enrolled under the GI Bill in what is now Columbia's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.

"In those days, students in architecture could audit any course in the University," says Mercado. "I took a class with Meyer Schapiro, one of the greatest teachers I ever ran across. He believed in his subject and he brought us into his world. Beyond painting, he had a wealth of knowledge of photography and related the two arts in his lectures. I learned how to look at paintings and to put the method of seeing into my photographs."

Mercado graduated from Columbia in 1949 "with an interest in big projects," and worked in the engineering side of city planning and architecture. In the 1950s, while on the staff of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, he headed the master planning for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. Later, with Parsons Brinckerhoff, he proposed a high-speed commuter line for the Long Island Rail Road and a train from JFK Airport to the city. After moving to California in 1971, he worked on redevelopment and public housing projects.

After the 1991 fire vaporized his home and nearly everything he owned, Mercado drew on the interests and skills that were first stimulated in bomb-flattened Frankfurt. He designed and built a new house, and bought a new camera.

Portrait of a Stranger

Mercado speaks of his art as documentary or street photography, but it might equally be seen as a kind of portraiture. For decades he used a twin-lens reflex camera (like the one he got in Belgium), which requires one to peer not through a little hole, but straight down at a ground-glass screen. This has the advantage of allowing the photographer to take a picture of the subject while looking at something else, but Mercado usually wasn't interested in sneaking up on anyone.

"I would start talking to the people I wanted to photograph," he explains. "'I like your clothes,' I'd tell them, or 'I like your face.' Then I'd ask if I could photograph them. The Rolleiflex is kind of a big camera, slow to operate, and I didn't want to frighten my subjects.'

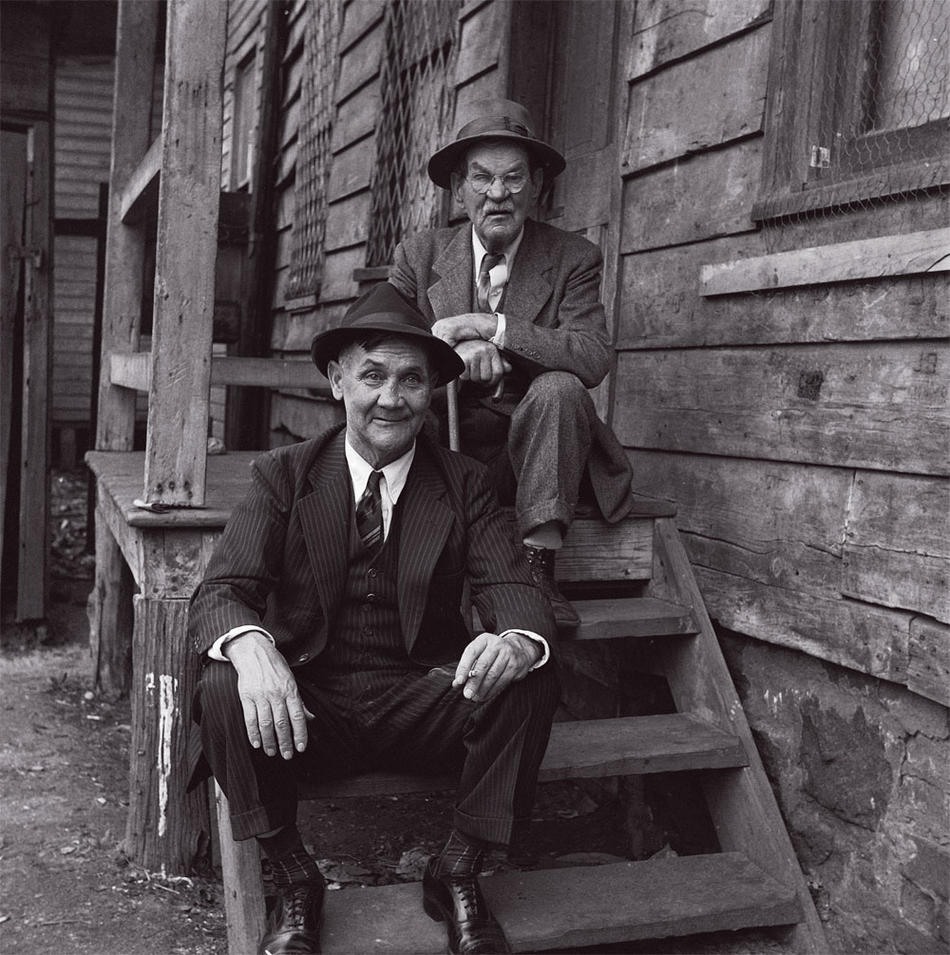

The result of this is that the setups of many of Mercado's pictures have a slight formality to them, as the subjects look him right in the lens. They're posing, of course, but they're posing right where the photographer caught them. They seem to be disarmed by Mercado's friendly approach. Would they look so different if they hadn't known they were being photographed?

He saw the nun on page 30 at Les Halles in Paris shortly before the old market was demolished in 1971. "I spoke to her in my terrible French and then asked if I could take her picture," he says.

Mercado approached the two immigrants in Jamaica, Queens, in a similar way. "I would wander through poor areas, and that's how I met these two men around 1946. You could see they had had tough lives, but here they were dressed in their Sunday best. They seemed dignified to me."

The photographs that Mercado took without preamble, such as the picture of the Greek newspaper reader or the Jewish shop owner in East Harlem, give us the sense that the photographer simply didn't want to disturb his subjects, not that he was trying to catch them. He makes one picture and moves on.

"Nowadays, people waste a lot of film," he says. "I was always a one-shot guy."