You’ve written a number of best-selling books aimed at helping people set and reach goals. This one is a little different. Could you explain why?

This book deals with an area of psychology called “person perception” — how we understand other people. Even after my many years of studying what people want, what happens when they get it, and what happens when they don’t, I am still shocked by how big the problem of being misunderstood really is. I wanted to write a book that gives a window into why people see us very differently than we think they do.

And why do they?

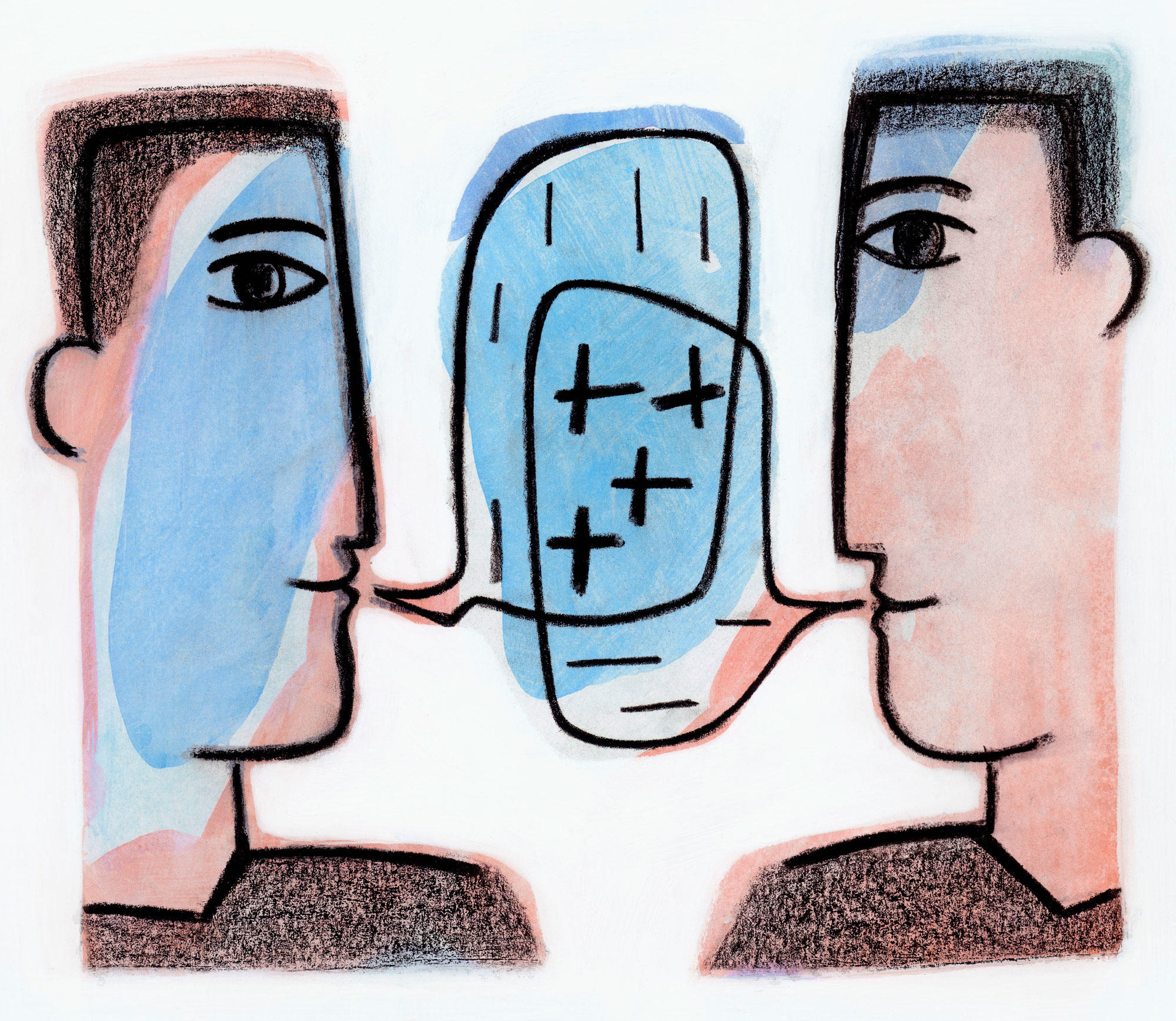

There is a tremendous gap between what we believe we are conveying and what people actually understand. This is called the illusion of transparency. We assume other people know everything we know; we routinely feel we said more than we actually did. But the truth is, aside from very basic and strong emotions like fear, disgust, and surprise, it is very hard to read one another. The face you make when you are a little annoyed at me looks very much like the face you make when you are not annoyed at all.

In one of your examples, a man is practicing his “active listening” face during a meeting, but this turns out to look just like his angry face, which scares his coworkers — the opposite of the intended effect.

Every look is open to multiple interpretations, and the perceiver has to figure out which one is right. So the misunderstanding is partly the fault of the perceiver and partly our fault, because we aren’t doing enough to make ourselves clear. Because perception is almost entirely automatic, people are not choosing to misunderstand you — they just are.

That sounds rather hopeless.

The good news is that while people may be really wrong about you, they are not randomly wrong about you. They are wrong in predictable ways. Once you understand that, and understand what kinds of behavior lead to these wrong perceptions, then you can do something about it. It’s important to understand how hard the perceiver’s job is. Even if someone is really paying attention, they still know very little compared to the information you have about yourself.

What are some concrete ways that people can make themselves better understood?

Instead of relying on facial expressions or gestures, articulate your message verbally. Listening is like trying to detect a signal in a whole bunch of noise. What you can do is make the signal really clear so the perceiver can detect it despite the noise. I also can’t stress enough how important it is to consider your audience. When I was first starting out as a graduate teaching assistant at Columbia, I went into the two-hundred-person lecture hall thinking that I needed to act as confidently as possible to show that I knew the material. I didn’t tell any jokes, or give off any signals of warmth. That might have been the right approach at an academic conference, but for college students, it was totally wrong.

In the book, you tell us that you abandoned chemistry for psychology during college. Why?

When you first study chemistry you learn about these incredible achievements — the discovery of electrons and how gases form, for example. Then you realize that it’s a fairly advanced field, and it’s not uncommon for a person to spend an entire career studying one protein. I took an intro psych course to fulfill a requirement and fell in love. Like many people, I thought of psychology as the domain of therapists and counselors and didn’t realize there was a whole scientific underpinning. And there is also so much more to know. Psychology as a science is only about one hundred years old. Nothing is more complicated than people — we are vastly more complicated than electrons and atoms.