I’m sitting in my office at the Harriman Institute, Columbia’s center for Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies, trying to pronounce “Kyiv.” “Kayv, Kih-yeev, Kih-yeeeeoooooo.” I stretch my lips and position my tongue. Across from me is Yuri Shevchuk, a Ukrainian linguist and senior lecturer at Columbia. I’m interviewing him for episode six of Voices of Ukraine, a podcast I’ve created about lives upended by Russia’s war.

Even here, in my community at Harriman, there’s no shortage of stories that need to be told: The alumna who’d spent months in Ukraine caring for her dying mother only to return to the US two weeks before the invasion. The student in the Slavic-languages department who’d been finishing his dissertation and planning a wedding in Kyiv when Russia invaded. The former faculty member who stayed in her Kyiv apartment through the shelling because her son, who’d joined Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces, was ill with COVID-19.

The podcast is halfway into its first season, but the correct pronunciation of the name of the Ukrainian capital still eludes me. I want to avoid pronouncing “Kyiv” the Russian way (Kee-yev or Kee-yef) at all costs. A Ukrainian-American colleague told me to say “Kayv.” My interviewees, mostly Ukrainians, tend to say “Kih-yeev.” Yuri, using the original, pre-Russification Ukrainian, pronounces it “Kih-yeeoo.” I practice, “Kih-yeeeeoooooo, Kih-yeeeeoooooo.” I feel like an imposter. But there’s Yuri, leaning back in his chair, cheering me on: “You say it very well. I don’t see anything wrong with the way you say it, other than self-doubting.”

Episode six is the first time I reveal to my audience that I am from Russia. This might explain the self-doubt.

I was born in Moscow in November 1982, just four days after Leonid Brezhnev, who’d ruled the Soviet Union for nearly two decades, died of a heart attack. No one knew he was dead; the authorities, worried that the news would send shock waves across the country, hid it for days. In lieu of an announcement, the state-run media broadcast Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake on repeat.

Airing Swan Lake would become a familiar trope during political upheavals in the Kremlin. Authorities played it after the death of Brezhnev’s successor, Yuri Andropov, less than two years later and after the death of Andropov’s successor, Konstantin Chernenko, almost a year after that. In 1991 it played on a loop for three days when hard-liners attempted a coup against Chernenko’s successor, Mikhail Gorbachev, who had opened the Soviet Union to the world with his policies of glasnost and perestroika.

The Gorbachev years are the ones I remember. The contrast between the drab scarcity around me — peeling paint, empty grocery shelves, unsmiling passersby in muted colors — and the new influx of brightly dressed foreigners made a huge impression. My mother, a young psychologist at Moscow State University, eagerly befriended those foreigners, inviting them to our communal apartment. They brought me presents and left me longing for a faraway world of Barbie dolls and pink bubblegum.

I am an only child. My dad, who’d once served as a navigator in the Russian navy, fed my wanderlust with stories about Europe, Japan, Chile, and Peru. As a Jew, he was discriminated against and regarded with suspicion by authorities; he had little loyalty to the Soviet Union. At school I pinned a red star to my uniform and sat with my hands neatly folded, listening to narratives valorizing the Communists. At home, it was made clear to me that the Communist regime was cruel and unsuccessful.

In 1991, when I was eight, my mother applied to graduate school in New York. My dad urged her to go, even though he would have to stay behind because of visa issues. We landed at JFK on a hot and humid July morning. The city seemed chaotic, but it didn’t matter: Americans smiled a lot, and there were bright toys, breakfast cereals, TV shows, and endless amounts of candy. My mother and I bounced between apartments of acquaintances, and she worked menial jobs to pay for our expenses. We both had recurring nightmares that we were back in Russia.

That summer I learned English by watching television shows: Full House, Saved by the Bell, Charles in Charge. When my dad called, I sang him the theme songs, which I knew by heart. By the time I started third grade in the fall, I could speak well enough to interact with classmates. But my accent hadn’t disappeared yet, and my clothes were all wrong.

A few months later, the Soviet Union dissolved overnight, and my dad joined us in the US. My parents spent their days looking for permanent work. Meanwhile, I rapidly assimilated into American life. As the years went by, I felt less and less Russian. Wanting to put our past behind us, my parents encouraged the shift. By early adolescence, I replied to their Russian in unaccented English. Yet they still cared about their birthplace and tried to get me interested in Russian politics. They felt uneasy when a former KGB officer named Vladimir Putin came to power, but I barely paid attention. In college, I majored in history and politics and studied abroad in Prague, where I learned Czech. Soon after, we were approved for US citizenship, and I swore an oath to the United States of America.

It was around this time that the color revolutions started: first the Rose Revolution in Georgia in 2003, then the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004, and then the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan in 2005. My parents followed these events closely and tried to involve me in their conversations about them. My mother even dragged me to a panel discussion about Ukrainian politics at the Harriman Institute in 2007. I daydreamed as the speakers clicked through their PowerPoints. Back then, all I knew of Ukraine were faint memories of my mom’s Ukrainian aunt and her children coming to stay with us after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, and the fact that half my mother’s family — her paternal Jewish side — was from Kyiv. My mother spent summer vacations there and always romanticized the city and its beautiful architecture. But in those times, Russia and Ukraine were portrayed by Soviet authorities as one country. The Kremlin downplayed the importance of nationality and emphasized that Russians and Ukrainians were family (a family that treated the Ukrainians as provincial, uneducated younger siblings).

When my mother took me to the panel on Ukraine, I was about to start an MFA program in creative writing and was looking for a job that could support me through grad school. Coincidentally, a friend told me that Harriman Institute director Catharine Nepomnyashchy ’87GSAS was looking for a Russian-speaking assistant. I landed the job, and suddenly Russian, Eurasian, and East European politics and culture became a regular part of my life.

One of the first events I attended at Harriman commemorated Anna Politkovskaya, a Russian journalist who in 2006 had been gunned down with impunity in the lobby of her Moscow apartment building. No one really knows who wanted Politkovskaya dead or why, but she had become well-known to Kremlin loyalists for her critical reporting on Russia’s war in Chechnya and the human-rights abuses there. By that point, Putin had consolidated much of the independent media that had flourished during the Yeltsin years under state control. The more I learned about my native country, the more people like Politkovskaya awed me. Instead of leaving Russia as my family had, they risked their lives to make it a better place.

In 2008, I returned to Moscow for the first time in seventeen years. I roamed the city, visited my grandmother’s apartment, and caught up with family friends over elaborately prepared meals. During that trip, a queer friend took me to a gay club. Sex between men was banned in Russia until 1993, and twenty-five years later, homophobia was still rampant. We walked through a dark alleyway to a hidden entrance, where a bouncer assessed us for signs that we might be a danger to the patrons. The experience left a mark. A few years later, the Russian government passed a law that “protected” minors from LGBTQ+ “propaganda,” unleashing even more homophobia.

I volunteered to interpret for a gay man who’d fled Moscow to seek asylum in the US after thugs beat him up. I grew increasingly interested in the plight of LGBTQ+ Russians and eventually told this man’s story in the magazine Guernica. It was the first time I had reported such an in-depth piece, and bringing to light the experiences of a vulnerable person caught in a brutal system was deeply satisfying.

In 2018, I enrolled in Columbia Journalism School’s part-time MS program to study audio reporting. By that point, I was married to an American I’d met in my MFA program. I was also pregnant with our son (whom we would name Nicolai) and working full-time at Harriman. It took me three years to finish the J-school program, including a year of Zoom classes and pandemic parenting. At the post-graduation awards ceremony, I won a Pulitzer traveling fellowship to report a story abroad. I was already conducting video interviews with Maria Zholobova, a journalist and former fellow at Harriman. She’d recently fled to Tbilisi, Georgia, after police raided her apartment in Moscow and declared the news outlet she worked for “undesirable.” I decided to use the fellowship to go to Tbilisi and get a deeper understanding of the rapidly growing community of exiled Russian journalists. I scheduled the trip for early March 2022.

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. I didn’t sleep that night or the rest of the week. I could barely breathe. Every time I looked at my three-year-old son, I thought about the mothers in Ukraine being forced to evacuate with their children, leaving behind spouses to be conscripted. At home, we have a rule: no phones at the dinner table. But after Russia invaded, my husband and I were scrolling constantly, looking up periodically to tell each other about new developments. “Did you see that a missile hit the TV tower in Kyiv?” “The power plant in Zaporizhzhia has been taken over.” Sometimes we just texted Twitter threads from across the table. Nicolai demanded answers. So I told him that the country I was born in was trying to take over the country our relatives came from. “They’re fighting over who’s in charge.” It was a script I’d cribbed from a parenting psychologist on Instagram.

A week into the war, Swan Lake entered my life again. The Russian government closed TV Rain, the last remaining independent TV network in Russia, for spreading “fake information” about Russia’s “special military operation” (the use of the word “war” was now punishable by fifteen years in prison). I watched the journalists’ impassioned and optimistic speeches, their assurances that good would prevail over evil, and sobbed uncontrollably. As the last broadcast ended, Swan Lake filled the screen. It was both a sign of protest and a tribute to Ukraine, where Swan Lake became a potent symbol after the 2014 annexation of Crimea.

By this point, it was clear that I’d have to reschedule my trip to Georgia. I felt guilty for abandoning the Russian journalists, especially since the world was abandoning them too. The sanctions that foreign governments (and well-meaning corporations) levied against Russian citizens didn’t distinguish between the Russians who supported the regime and those who opposed it. Many good Russian people were stranded, their finances frozen, their PayPal transactions denied. I also felt a deep sense of guilt for being Russian, even though I hadn’t lived in Russia since 1991 and never supported the Putin regime. It was a feeling shared by many of my Russian friends.

I mentioned this guilt to my parents. But they only felt grief. “What do we have to be ashamed of?” my mother asked. “We have been anti-regime from the beginning.” She told me that she’d noticed a sense of antagonism toward Ukrainians seeping into Russian society years before the annexation of Crimea. The Russian government had created this enmity, pushing YouTube videos about Russian-hating Ukrainians and amplifying narratives about the Ukrainian far right on state television. Even people who opposed Putin believed the propaganda. “I would tell them, ‘The government is brainwashing you. Stop it,’” my mother said. But her friends would just shake their heads.

A Russian colleague at Columbia told me that the nineteenth-century composer Mikhail Glinka, when he emigrated from Russia, stripped his clothing at the border, wanting to cleanse his soul of Russian cruelty. “I felt similarly when I left,” the colleague said. But not everyone felt this way. Some blamed NATO for provoking the invasion. One Russian-American friend asked how I could possibly feel ashamed of the war against Ukraine since it was something I had no part in. “I feel much more shame about the war in Iraq,” he said.

The first week of the war felt like it lasted months. It helped to talk to colleagues and students at Harriman. Everyone was in some version of the same hell, and after hearing their stories, I had the idea for Voices of Ukraine. I pitched the podcast to my bosses and started interviewing right away. Yes, I was nervous. Anger at Russians was high, and understandably so. Would Ukrainians want to talk to me, a Russian émigré, while Russia destroyed their country? But everyone was gracious and eager to share their experiences. And I was struck by how strong, optimistic, united they were. We will win. When we win. When we return. I was also struck by how much Putin’s plan had backfired: he had hoped to pit Russian-speaking Ukrainians against Ukrainian-speaking ones, but instead, Russian speakers who had previously been indifferent to their identity, or even ashamed of it, were starting to speak Ukrainian in an act of protest.

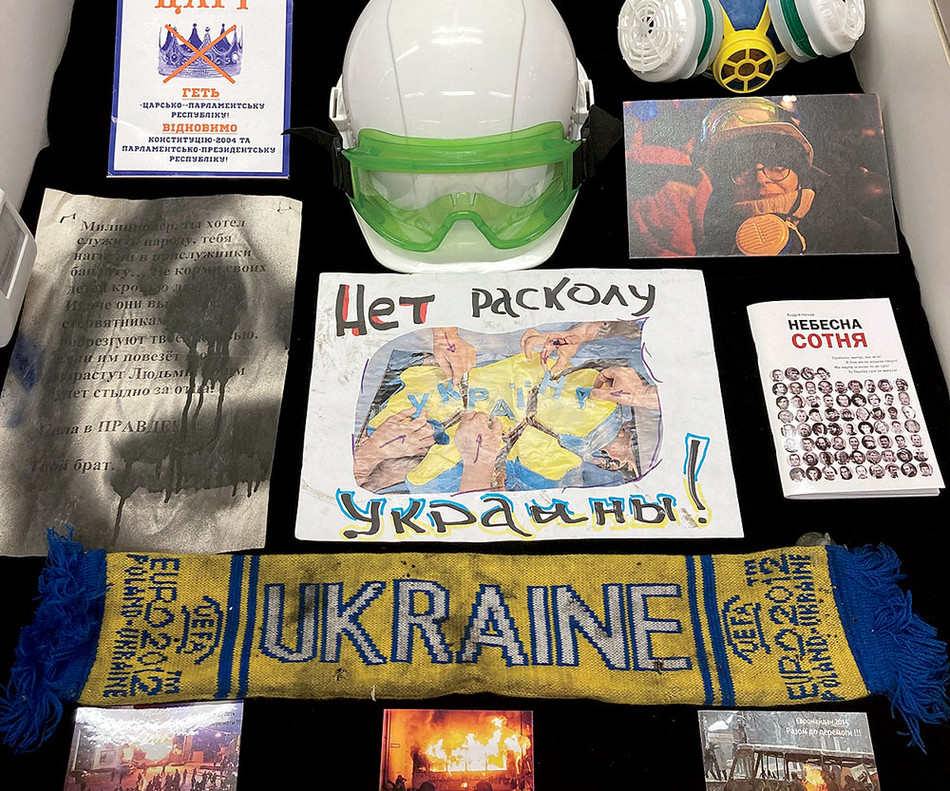

A week after I published the podcast’s season finale, I visited Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library to see an impromptu exhibit contextualizing the history of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. An archivist there, a Kyiv native and activist named Katia Davydenko, gave me a tour. Katia told me that when the world united to oppose Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, she didn’t feel pleased or relieved. She felt bitter: where was everyone when this started, eight years ago, when there was a chance to prevent Russia from going further?

As I walked by the display cases, listening to Katia’s stories about the thousands of ordinary people who had put aside their lives, and sometimes lost them, in the fight for Ukraine, I held back tears. I thought back to what I had been doing after the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of the Donbas in 2014. I remember being angry, of course. It baffled me that Russia could seize the territory of a sovereign country and get away with it. But I didn’t do anything. I was busy planning my wedding.

Now, as the war begins to recede from the headlines, I’m gathering stories for Voices of Ukraine, season two. Illuminating the heroism and struggles of Ukrainians is my small contribution to the fight, a way to counter Russian propaganda and remind the world about the war.

Recently, I shared the podcast with a neighbor I met in my apartment building’s laundry room. A week later, she sent me a message: “The heartbreaking first-hand accounts … have woken me out of my haze of day-to-day ‘challenges’ and impelled me to want to help relieve the suffering of Ukrainians in any way I can.” She asked me for the names of organizations that were accepting donations.

I’m glad the podcast is making some impact, even a tiny one, but I wish that I’d woken up from my haze years earlier. I can’t stop thinking about what Katia said: that if only the world had paid attention, maybe none of this would have happened.