He was forged in the steel town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, and his first coach was his father, a phys-ed teacher who also worked nights at the mill. He was crazy for football and made it to the Ivy League, to Columbia, where he wore the number 67 on his wiry 165-pound frame. He was small even for a linebacker, but more than once, his coach, Aldo Donelli, put him on the offensive line, among the giants.

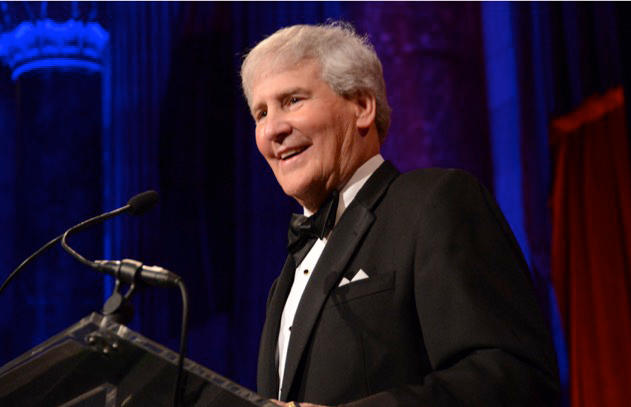

Bill Campbell ’62CC, ’64TC, ’15HON, who died on April 18 at age seventy-five, would become a giant himself. In 1983 he joined a young company, Apple Computer, Inc., as vice president of marketing, and eventually became the CEO of Intuit, the maker of the software applications Quicken and TurboTax. Along the way, Campbell made a name for himself as a preternaturally savvy management guru to tech titans like Steve Jobs of Apple, Larry Page of Google, and Jeff Bezos of Amazon. Campbell was “the Coach of Silicon Valley” — a shrewd, salty, bighearted, exuberant, high-octane mentor, of whom former Google CEO Eric Schmidt once said, “Our basic strategy is to invite him to everything.”

It was a strategy that Columbia was privileged to share.

“Bill was a beloved alumnus, football coach, trustee, former Chair of the Trustees, and, above all, a friend and source of boundless joy and counsel to everyone who knew him,” President Lee C. Bollinger wrote in a letter to the Columbia community on April 18.

At Columbia, Campbell was captain of the 1961 football team, which won the only Ivy League title in Columbia’s gridiron history. He got a master’s in education from Teachers College, then worked as an assistant football coach at Boston College before returning to serve as head coach of the Lions from 1974 to 1979. After leaving Columbia, Campbell got a job with an advertising agency, which led to a gig with Kodak in Europe — his last stop before heading to Northern California.

The Coach of Silicon Valley had a few points aggressively underlined in his corporate playbook. He emphasized product innovation as the key to a company’s survival; warned that internal conflict can bring a company to its knees; and viewed engineers — not product managers or salespeople — as the most important players in a company’s success. Then there was his personal playbook, which was all about giving back, in ways big and small, without fanfare.

Though Campbell’s life was based in Palo Alto — he even owned a bar there, the Old Pro, where he often held court — he never forgot his roots back East. He became a University Trustee in 2003 and was appointed board chair in 2005. Over the next decade, Campbell helped guide Columbia through a period of growth that included the Manhattanville expansion, a record-breaking capital campaign, the creation of the Columbia Alumni Association (CAA) and Global Centers, and the opening of the Campbell Sports Center. Campbell became chair emeritus of the Trustees in 2014, and received an honorary degree last year.

When news of Campbell’s death reached Columbia, the flags on the playing fields at Baker were lowered to half-mast and the number 67 was painted on turf on either side of home plate at Robertson Field. No member of any Columbia varsity sports team will ever wear the number again.

On April 25, in Atherton, California, some two thousand mourners gathered on the high-school football field where Campbell had continued to coach middle-schoolers. The funeral service included a eulogy by Campbell’s teammate Lee Black ’62CC and a gospel song sung by Ted Gregory ’74CC. Afterward, hundreds of Campbell’s family and friends, including President Bollinger, Columbia Trustees chair Jonathan Schiller ’69CC, ’73LAW, and former CAA chair George Van Amson ’74CC, repaired to the Old Pro in downtown Palo Alto to raise a glass to the Coach.

“Bill was a one-of-a-kind, truly unique human being,” Bollinger told the crowd. “He was brilliant at friendship and had a genius at making groups and institutions be their best. The Campbell name will deservedly grace countless buildings, programs, scholarships, and awards. But Bill’s friendships are the most enduring of all.”