Early film criticism was largely the work of moonlighters, as editor Phillip Lopate ’64CC in American Movie Critics: An Anthology From the Silents Until Now calls those poets and filmmakers “who tried their hand at it for a few years, then moved onto their preferred métier.” Not until the mid-1930s — approximately 20 years after feature filmmaking began in the United States — did the film critic finally get hired full-time. That is, when Otis Ferguson first began reviewing movies for The New Republic. “What Ferguson ‘got,’” Lopate writes in his introduction to the anthology, “was the genius of the Hollywood system, the almost invisible craft and creativity of the average studio movie.”

The film critic must achieve the usual feats in criticism: to limn an entire work of art in just a few hundred words; to say something fresh, even about flops; to engage in politics, but not too much; to be open to reversing opinion, but not too often. But above all, the film critic must appreciate filmmaking — as a whole unto itself and not just as the sum of theatre’s, literature’s, and photography’s parts. In a time when most critics still condescended to write on film, Ferguson acknowledged the intellectual bias against much film criticism: “There are those who will . . . say, If you’re going to chat about the stars, you’re no kind of critic and to hell with you.” Ferguson, in turn, states that “a film story without people is like a novel without a character, music without a sound,” delivering his case in point: Mae West in Belle of the Nineties. “Miss West . . . makes her own personality such a focus for a whole picture that its merits become to some extent its defects as well.”

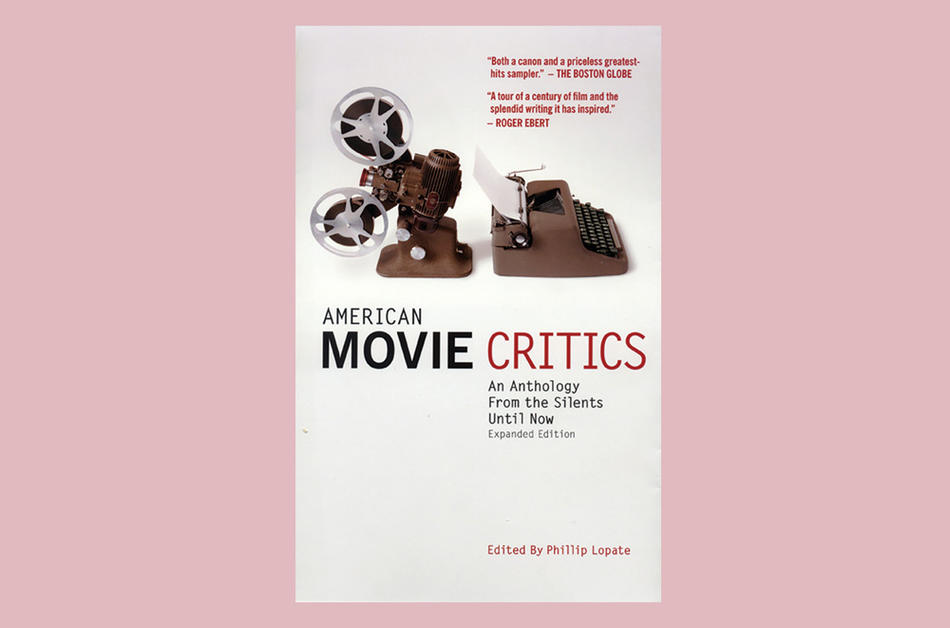

Lopate is a film critic, essayist, novelist, and poet, but it is the professor in him who confidently guides the reader to his favorites such as Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, Pauline Kael, or Andrew Sarris ’55CC, ’98GSAS. “My main criterion for selection has been personal,” Lopate writes, “I either liked or didn’t like the way a piece of criticism was written.” Lopate’s discerning eye may be familiar to readers of The Art of the Personal Essay, an impeccable anthology composed of works so diverse — from Seneca to Montaigne to Fitzgerald — that it came close to the impossibility of being all things to all readers. With a focus narrower in pursuit, American Movie Critics must content itself with being only one thing to one reader: indispensable to the budding film critic.

While American Movie Critics includes reviews of seminal films such as Citizen Kane and Pulp Fiction, it is by no means a greatest-hits list à la AFI’s 100 Years . . . 100 Movies. Rather, it charts the arrival, acceptance, and persistence of film criticism — from Vachel Lindsay’s 1915 essay “The Photoplay of Action” to Manohla Dargis’s review of A History of Violence (2005). Lopate organizes chapters according to writer, emphasizing each individual’s style, although muddling film history. Lopate is, after all, more concerned with what a critic says than what he saw: “I have focused on film criticism as an art in itself — the magnet for strong, elegant, eloquent, enjoyable writing.” For this reason, American Movie Critics serves as an introduction to the practicing critic, that “kind of old friend whose conversation we cherish and to whom we turn eagerly for opinions and advice.” Between veterans such as Andrew Sarris and newcomers like A. O. Scott, the moviegoer is bound to make a new friend in time for Oscar season.