Shortly after his inauguration in 1789, George Washington undertook a series of tours to get to know his country. Realizing that if he spent the night in the home of local eminenti he would gratify one and outrage the rest, he determined to stay in inns. He recorded the quality of his accommodations in his diary; perhaps he should have published his comments as a guidebook. They range from laconic satisfaction ("The People of it were disposed to do all they could to accommodate me") to devastating, if equally laconic, dissatisfaction ("no Rooms or beds which appeared tolerable, & everything else having a dirty appearance"). Indeed, the latter establishment got a rating of George Washington Did Not Sleep Here: "I was compelled to keep on."

In Hotel: An American History, Andrew K. Sandoval-Strausz '94CC convincingly demonstrates that the infant republic created the hotel and then the hotel helped the republic toward maturity. This excellent book is a wonderful example of illuminating scholarship for a general audience. Sandoval-Strausz, who teaches history at the University of New Mexico, gives us not only the history of an American business, but also explains how the hotel was at once both a public and a private space, with the hotelkeeper's implied obligations to welcome travelers — and sometimes explicit rights to turn them away.

It may be only coincidence, but the Washington administrations — the 1790s, roughly saw the development of enterprises that moved from public houses and inns to something much nearer to the modern hotel: large buildings with scores, sometimes hundreds, of private rooms and a considerable range of services, including what would now be called banquet and conference facilities. Some of these hotels never got past the drawing board and a failed IPO, but some were built, notably the Exchange Coffee House in Boston.

This institution typified the first wave of hotel building in the new country. Its investors were largely merchants in foreign trade, and mostly Federalists. Among other purposes, the Coffee House provided a decorous venue for the political meetings of the best people, and when it burned down in 1818, there was open rejoicing amongst the emerging democracy's citizens. One can guess that John Adams cast an approving eye at Boston's first hotel, and his radical cousin Sam, a jaundiced one. A similar partisan tinge marked other early hotels.

By midcentury, Europeans looked to America as the standard. In 1854 a British visitor said of a hotel in Cape May, New Jersey, that "an Englishman has some difficulty in believing that such a structure can be a hotel." The English man of letters George Augustus Sala observed that "an American hotel is to an English hotel what an elephant is to a periwinkle." He concluded that he thought American hotels a century ahead of England's.

As hotels continued to provide more than food and lodging for travelers, they expanded their early role as venues for political parties. In 1860 the Democrats held a national convention at a hotel in Charleston where southern delegates sundered their party and lit the fuse that led to the Civil War. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1862 that the Willard in Washington, not the Capitol, was the real center of political activity. In 1920 the Republican leadership cut out of its Chicago convention's deadlocked plenary session and sequestered themselves in the famous smoke-filled room in the Blackstone Hotel to nominate Warren G. Harding (and not Nicholas Murray Butler) for president.

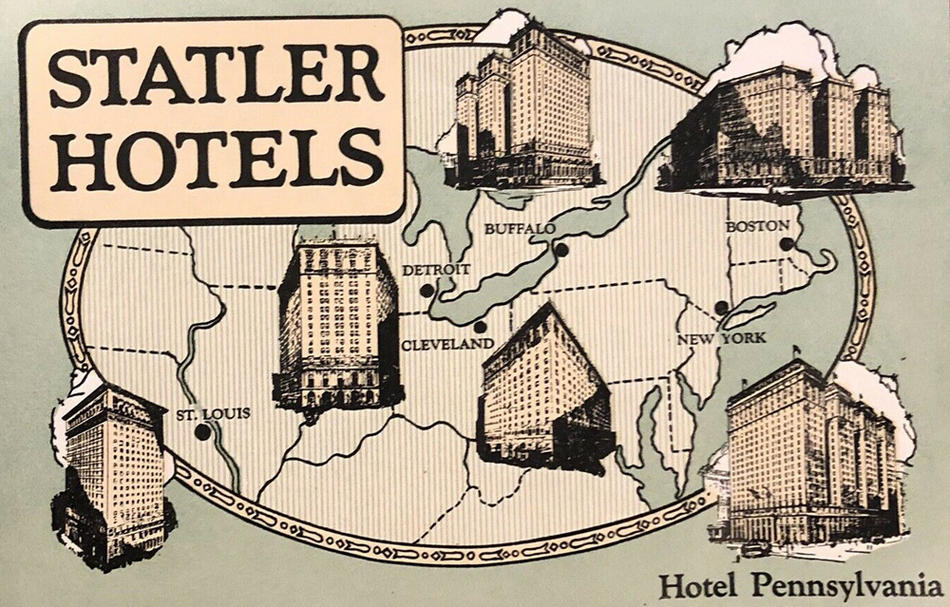

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, a serious hotel was sure to be one of the most imposing buildings in its city, the grandeur of its exterior promising luxury within. This was changed 100 years ago by E. M. Statler, who was to hotels what his good friend Henry Ford was to automobiles. Statler noted that while he could build grandiose hotels, he did not want to. His view was succinct: "I don't operate in that field. To hell with it." Statler's buildings were plain of exterior and located away from the high-rent district. He used his savings to keep prices down and the supply of useful amenities up. His celebrated motto was "A bed and a bath for a buck-and-a-half." He produced the standard American hotel of today and inspired its Ford-derived cousin, the motel.

Sandoval-Strausz's complex tale of two centuries is told from the viewpoint of an eagle that sees the whole landscape. He is a master of context, such as the development of hotels as parts of transportation networks, the emergence of the apartment house from the residential hotel, the power of resort hotels to build permanent communities (what might be called Florida Effect), and the evolution of the common law of the innkeeper into codified law, a point he explores with real acumen, especially on the subject of civil rights. "The common law of innkeepers and carriers," he writes, "became the key to racial equality in public places."

He makes a solid case. Even in the wake of the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection of the law, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, blacks (and, to a lesser extent, Jews) were banned from hotels in great swaths of the United States — and not just the South. This endured into the 1960s, and Sandoval-Strausz mentions a number of embarrassing cases when rooms were denied to visiting international dignitaries because of their color. This type of exclusion would eventually be at the heart of the civil rights struggle.

These topics barely suggest the range and depth of Sandoval-Strausz's erudition and the lucid skill with which he deploys it. He knows the possibilities hotels have offered for human depravity and what hotelkeepers have done to limit them. He understands why the desk clerk became necessary and how his profession developed, and he gives the impression of having been a guest at representative hotels over the last two centuries - or even among hotel mavens momentarily elsewhere. One of the memorable scenes in Babbitt takes place in a Pullman smoker as travelers compare and contrast the Statlerized hotels of the 1920s. Had Sandoval-Strausz been aboard, one imagines that he would have known every hotel mentioned by Lewis's salesmen-connoisseurs, added his own observations, and silently reflected on where these hotels had come from and where they were going.

Not the least virtue of this book is the copious supply of illustrations, showing us what hotels looked like in their formative stages. For these, we are in debt not only to the author, but to a publisher who still understands how books should be made.