Sophy Roberts ’97JRN is a travel writer with serious cred. She studied English at Oxford, worked as an assistant to author Jessica Mitford, and trained as a journalist at Columbia before becoming a regular contributor to the Financial Times and Condé Nast Traveler. Now she voyages to remote parts of the world to hunt for disappearing cultures, endangered wildlife, and colorful members of her own species. In her first book, she bags all three.

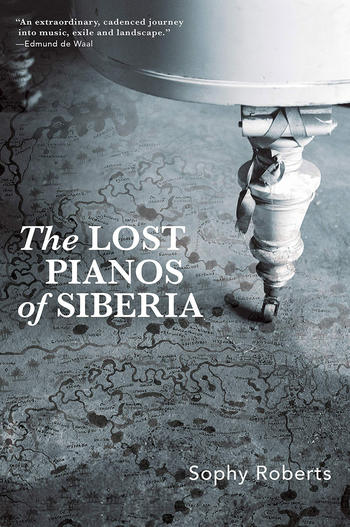

The Lost Pianos of Siberia tells the story of Roberts’s journey into the vast wilderness east of the Ural Mountains in search of a Russian piano with an interesting provenance. “Violent. Cold. Startlingly beautiful. That stately instruments might still exist in such a profoundly enigmatic place as Siberia feels somehow remarkable,” writes Roberts.

The quest begins in the summer of 2015 in Mongolia, where Roberts attends a piano recital in a tent “pitched a long way from where the road runs out in the fenceless steppe.” Her friend who has organized the evening is frustrated. The young pianist is talented, but the modern baby grand is lacking. The friend leans over and whispers to Roberts, “We must find her one of the lost pianos of Siberia.”

Roberts knows little about Siberia and less about pianos, but the idea is catnip to her romantic sensibility and love of adventure. “The more I listened to her play, the more I wondered how an historic piano would sound different in the steppe — an instrument which still resonated with the gentler timbre of the nineteenth century.” The quest is implausible, its outcome decidedly uncertain, but as a travel writer Roberts knows that the journey, not the destination, is all. As she says, “If we could do it, it would be good, and a good story. And if we couldn’t do it, we would have a story too.”

And so the hunt begins, but what starts with whimsy results in a travelogue that is deeply sensitive to the mystical pull of the Siberian landscape, precisely informed by investigative journalism, and rich in Russian history.

As she pursues her quarry, Roberts details Siberia’s brutal role as a penal colony, one used not only by the Soviets, who created the forced-labor camps known as the Gulag, but by generations of tsars who banished their political enemies to the frozen wasteland. Siberia was also the site of the violent end of a three-hundred-year-old imperial dynasty when, in 1918, Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, and their five children were murdered there.

We also learn about the importance of the piano in Russian society. How under Catherine the Great, an appreciation for European culture — especially its music — was considered a mark of social standing and respectability. How in the 1840s, Franz Liszt’s smashing performances (literally — he broke several instruments on every tour) and the resulting Liszt-omania helped spur Russia’s nascent piano-manufacturing industry. Roberts details how some of those pianos eventually found their way to Siberia and how the tsar’s political exiles, many of whom were wealthy and privileged, brought music education to the hinterlands.

Roberts’s search will entail several trips to Russia, and as she journeys east across Lake Baikal and visits remote towns and villages, we come to understand that the piano is but a minor player in this adventure. What’s more compelling is the cast of picaresque characters, both living and historical, who understand the transformative power of music and its essential role in their lives and culture. These men and woman not only cherish their pianos but carry them to the ends of the earth. “How such instruments travelled into the wilderness in the first place are tales of fortitude by governors, exiles and adventurers,” says Roberts. “The fact they survive stands as testimony to the human spirit’s need for solace.”