As I rode in from Sheremetyevo Airport on the morning of December 10, 2011, the streets were nearly empty. Then, as we crossed the Garden Ring road to enter central Moscow, I saw the first security forces and personnel carriers. When we approached the Kremlin, riot police in full gear were preparing to take their positions, and as we passed over the Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge, a long line of buses and police wagons waited to take demonstrators to jail.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Everyone expected that — with some creative counting by the Central Election Commission — the December parliamentary elections would give a solid majority to the ruling United Russia Party. Then the March 2012 presidential election would certainly return Vladimir Putin to the presidency without incident.

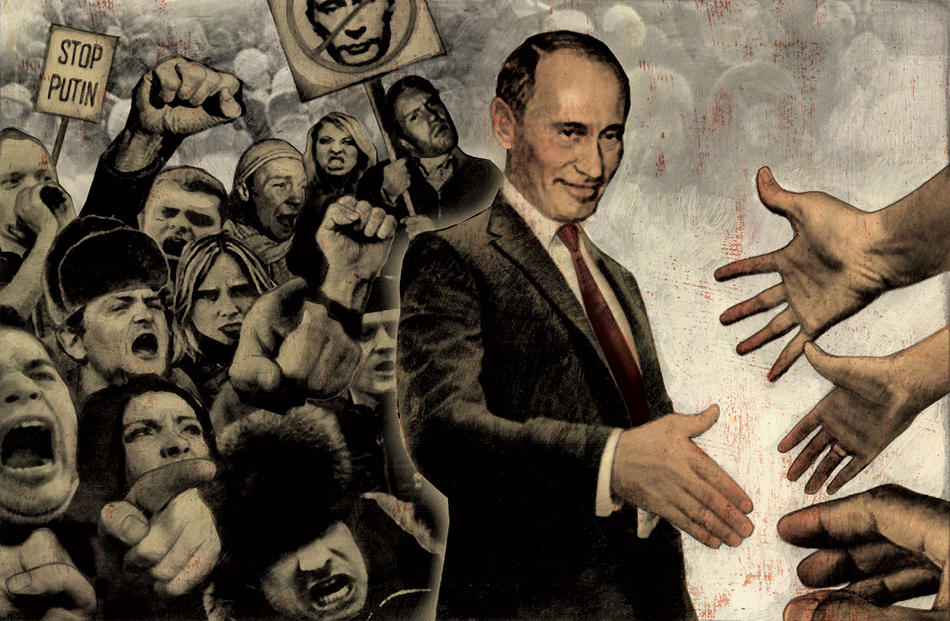

Yet now, six days after volunteer election monitors began posting YouTube videos of ballot stuffing, vote fraud, and multiple voting, some forty thousand demonstrators gathered on Bolotnaya Ploshchad (Swampy Square) in central Moscow to protest that fraud and call for new elections. In a rare show of unity, nationalists, liberals, and leftists put aside their divisions to direct their grievances toward the Kremlin. The mood was more akin to a carnival than a revolution. One poster mocked Putin’s alleged use of Botox. Another offered election-commission chairman Vladimir Churov a copy of Counting Votes for Dummies. Police officers looked on while deciding whether the weight of the protesters would collapse the bridge over the Moscow River.

Two weeks later, on Christmas Eve, that solidarity was still holding, as one hundred thousand demonstrators gathered on Andrei Sakharov Square in Moscow. Emboldened by the Kremlin’s feeble response, speakers took turns denouncing the government for its corruption and calling on Putin to resign. Demonstrations continued in the run-up to the March 4 presidential election.

Considering that these were hardly the first fraudulent elections in Russia, the size of the protests surprised everyone, including the demonstrators themselves. In the days before the demonstrations, a Russian journalist friend bet me that no more than five thousand people would join him at the first protest. In the end, an academic colleague said that the demonstrations were like a school reunion: he ran into many friends whom he had not seen in years.

Most of the demonstrators appeared to come from the middle class, a group that had prospered under Putin. Thanks in large part to high energy prices and sound macroeconomic policy, Russia’s economy doubled between 1998 and 2008 and rebounded quickly from the global financial crisis. Russia’s GDP per capita stands at more than $16,000, significantly outperforming its emerging-market peer group of Brazil, India, and China. Moscow’s standard of living rivals that of southern Europe, and Russia has the largest Internet market in Europe, with more than fifty million users. One poll estimated that roughly 70 percent of demonstrators at the December 25 protest had attended college. One Kremlin insider referred to the demonstrators as the “best people” of Russia. For this and other offenses, he was unceremoniously demoted.

Alexei Navalny, a thirty-six-year-old lawyer turned anticorruption activist, is the most prominent of a new generation of opposition leaders to emerge from the demonstrations. He won his fame by scouring the purchasing requests of state-owned companies on the Internet and publicizing the most egregious abuses on his organization’s website, Rospil.ru. Navalny rallied the opposition by branding the ruling elite “the party of crooks and thieves” and helping to attract popular literary figures, such as the writer Boris Akunin, and celebrities, such as Ksenia Sobchak, Russia’s own Paris Hilton. Protesting became cool.

Within a few weeks, the demonstrations had pierced Putin’s aura of invincibility. Protesters were bold enough to hang a large banner opposite the Kremlin calling on Putin to resign and to circulate a fake news report on the Internet showing Putin on trial in a Moscow courtroom. Staging these events would have been unimaginable a few weeks earlier.

The demonstrations caught the Putin administration off-guard. After initially blaming Hillary Clinton for the disorder, Putin mocked the protesters’ white ribbons, saying they reminded him of condoms. His usual mix of machismo and pointed humor failed badly. But he soon regained his balance and turned the tables on the demonstrators. His team organized large counterdemonstrations, including one on February 4, in which 120,000 Putin supporters turned out in western Moscow to counter an equal number of anti-Putin demonstrators gathered in the center of the city.

Putin also decided to change his strategy. In previous years, he had found favor with both the middle class and the lower class: economic growth had helped him draw support from the emerging middle class, and increased state spending had gained him favor from socially vulnerable pensioners, state workers, and rural populations. However, the demonstrations and voting patterns in the parliamentary elections indicated that Putin was losing the young, urban, and educated populations, and that his supporters were now older, more rural, and less well off than in previous elections. Putin’s campaign turned to populist economic policies to appeal to this audience by raising pensions and salaries for the military and many other state workers.

Putin also played the nationalist card with fervor. His campaign’s most common tactic was to accuse the demonstrators of being in league with foreigners, often in the employ of the US government, who were intent on dismantling Russia. His pre-election foreign-policy platform mentioned only two potential enemies: NATO and the US.

On March 4, with thousands of security officers in full riot gear on the streets, Russians cast their ballots for president. The results surprised no one: only Kremlin-approved candidates were permitted in the race, and Putin’s faux foes included two four-time losers of presidential elections (Zyuganov and Zhirinovsky), a thoroughly compromised ally (Mironov), and a political neophyte, albeit a wealthy one (Prokhorov). Incumbents who choose their opponents tend to do well; Putin won 64 percent of the vote.

As the day progressed, blatant ballot stuffing by election officials appeared to be less of a problem than it had been in the parliamentary elections, thanks in part to newly installed webcams at polling places. But videos showed busloads of voters touring from one polling station to the next, and reports came in of company bosses using threats of dismissal to motivate their employees to vote. As usual, votes for Putin in many of the largely ethnic republics were well above 85 percent — figures that stretch credibility.

This is not to say that Putin is unpopular, nor that he could not win a free election under the scrutiny of a free media and critical questioning by rivals. The problem is that we have no idea whether he could or not.

For all the drama of the protests, Russia’s future will be shaped by deeper structural factors, such as its resource-dependent economy; well-educated public; vast regional inequality; and aging, shrinking population. Yet the elections have left their mark. To begin with, they have revealed Putin’s vulnerability. His approval ratings fell from 80 percent in June 2010 to 44 percent in December 2011, before rising to the mid-50s in March. These would be enviable figures in many settings, and Putin faces no clear rival among established politicians; but Putin fatigue has clearly set in even among those who still support him, and it is hard to see how the government can generate the enthusiasm needed to tackle the country’s economic and social problems.

The elections and demonstrations also indicate that Putin will face a more engaged public than in the past. The new activists are likely to push for greater media freedom and use the Internet and social media to keep tabs on the government from the outside. These activists, with their high levels of education, wealth, and social standing, will play a crucial role in economic reform and the future of the country. Still, for all their efforts, they have little organization or political power. The hard work of creating parties, winning local offices, and building alliances lies ahead. The Putin administration has organization but little energy, and the opposition has energy but little organization.

A diminished leader facing a weak opposition is hardly a recipe for addressing deep problems. More likely, we will see political and economic changes at the margin — a privatization here, greater media freedom there, and selective crackdowns on corruption — but not the introduction of policies that would destabilize the Putin government and the status quo. Not that maintaining the economic status quo is bad for the short term. Russia’s economy is growing on the order of 3 or 4 percent a year, which is impressive compared with Europe and the United States. The Putin administration has done a good job managing its oil bonanza and has built enviable reserves of foreign exchange; but in the long run, the country needs better governance and an influx of foreign capital.

The impact of the election extends well beyond Russia. A nondemocratic Russia will continue to support friendly autocrats in the region and frustrate groups pushing for political liberties outside Russia.

The election has also complicated US–Russian relations. The Obama administration had been in a good position to point to some real achievements with Russia. In recent years, the two sides have concluded a new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, known as New START, which will cut the number of strategic nuclear-missile launchers in half. They have cooperated on transporting US troops through Russian airspace to fight in Afghanistan. With some pressure from Washington, Russia has limited its sales of missiles to Iran, and, after more than seventeen years of negotiations, Russia has finally gained entry to the World Trade Organization. But Putin’s anti-US campaign rhetoric and Russia’s flawed elections have emboldened critics of Obama’s Russia policy at home, especially those with an eye on the November election in the United States. These critics accuse Obama of abandoning those fighting for democracy in Russia.

Putin takes the inaugural oath on May 7. Organizers are making plans for large protests to mark the event. It is not likely that the opposition will surprise the regime again.