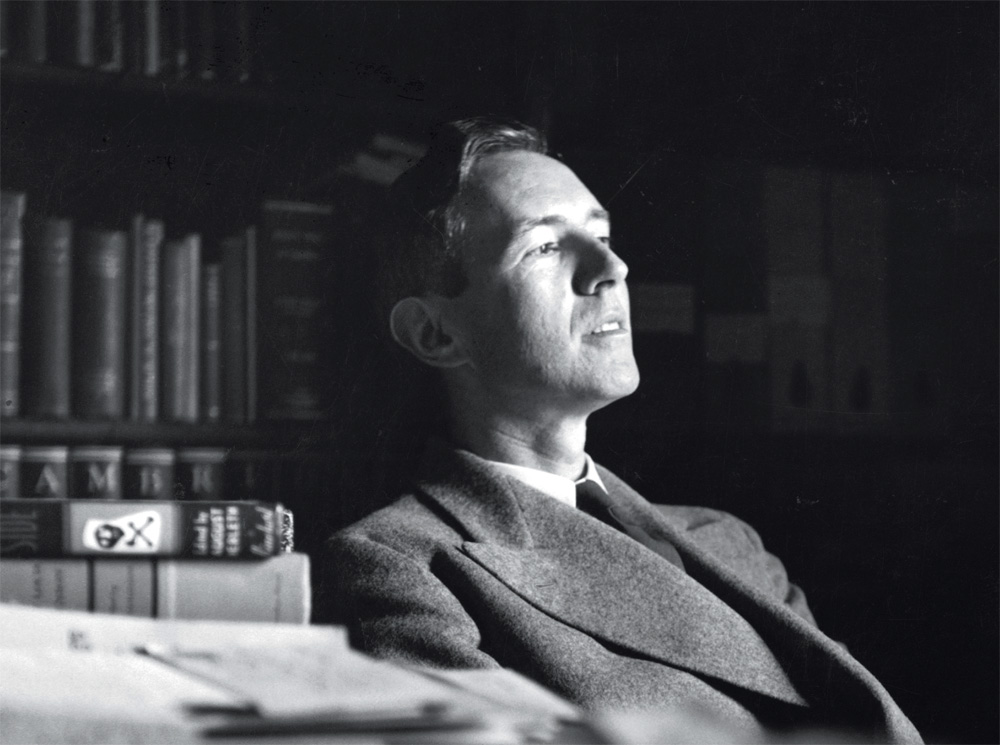

This academic year, Columbia commemorates two anniversaries: the 100th birthday of the great Columbia intellectual scholar Jacques Barzun '27CC, '32GSAS and the 40th anniversary of the events that disrupted and closed the University for a week in 1968.

Born on November 30, 1907, Barzun came to Morningside Heights as a freshman in 1923. Forty-five years later, as University Professor, he stood as one of the pillars of reason during America's most notorious campus uprising. Now living in San Antonio, Barzun was awarded the 59th annual Great Teacher Award by the Society of Columbia Graduates on October 18.

Columbia magazine asked William R. Keylor, one of Barzun's last doctoral students, to reflect on his relationship with his mentor during that tumultuous period in the history of the country and the University.

When I arrived at Morningside Heights in the autumn of 1966, the civil rights movement was in full bloom and discontent with the war in Vietnam was escalating. Columbia had become a magnet for all manner of social protest, with earnest advocates of this or that cause mounting the sundial daily to press their case before increasingly agitated and politicized students. In the following academic year the Tet offensive, the McCarthy presidential campaign, the Johnson withdrawal, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., produced an atmosphere of political activism on campus that spawned the student uprising against the University in the spring of 1968.

With students ensconced in several Columbia buildings while the New York City police ominously assembled nearby in preparation to eject them, many luminaries of the Columbia professoriate descended from their ivory tower to wade into the boisterous debates that reverberated throughout the campus. They lined up on both sides of the barricades, some loudly denouncing the students as spoiled children of privilege who were interrupting the vital work of the University, a few others endorsing the students' case against Columbia and even expressing tolerance of their disruptive behavior. I vividly recall that, in spite of what one would assume to be the former provost's opposition to the actions of the demonstrators, Jacques Barzun was unfailingly courteous to those of his students who declared their support — some with unbridled enthusiasm, others with many caveats — for the occupation. Amid this Sturm und Drang he offered an alternative model of serenity and rationality, behaving as someone who, unlike many of his colleagues, had never lost his bearings.

The forcible removal of the students from the buildings on April 30, 1968, which resulted in a few injuries and many emotional scars, sparked a University-wide strike that in turn led to the cancellation of several classes. Shortly thereafter, the students in Barzun's graduate seminar on modern European intellectual history received a brief note from him inviting us to meet in his spacious office in Low Library at the regular hour. As we gathered around his conference table, he gently inquired if the class might reconvene the following week in its assigned room in Philosophy Hall. Those of us who had been swept up in the twin passions of the moment — abhorrence of racism at home and of the war in Southeast Asia — were loath to cross the picket line that had been thrown up around the classroom buildings. Taking note of the embarrassed silence with which his suggestion was received, Barzun cheerfully agreed to let us off the hook by offering his office for future meetings. We thus returned to the intellectual labor that had been interrupted by the momentous events outside the classroom, devouring the books on his lengthy reading list covering the cultural history of Europe since the Enlightenment. Once we got down to business, I was immediately struck by the glaring contrast between the red armbands, bullhorns, and revolutionary rhetoric still very much in evidence along College Walk and, to take but one of our reading assignments, the "art for art's sake," "love for love's sake" romantic romp in Théophile Gautier's Mademoiselle de Maupin.

In the years after the student unrest of 1968, everyone at Columbia was struggling to make sense of it all. Under Barzun's guidance, I was hard at work on a dissertation that touched on an earlier episode of youthful protest. The student movement at the Sorbonne before the First World War that I was investigating stood at the opposite end of the political spectrum from the one I had witnessed and played a very minor role in at Columbia. The French students were right-wing nationalists who denounced their university for betraying the conservative values of God and country. We were liberal idealists criticizing our university for acquiescing in racism (through a plan to build a gymnasium in Morningside Park for its predominantly white student body), and militarism (through its affiliation with a shadowy think tank that conducted classified research for the Pentagon, which was waging the repugnant war in Vietnam).

In our conversations in his office we shared our different perspectives on student activism past and present. Barzun reiterated his conception of the proper role of the university that had already appeared in such works as his The House of Intellect and The American University. His message was loud and clear: The primary purpose of academic research is the unfettered search for truth, and the primary purpose of college teaching is broad instruction in the liberal arts. The professoriate must never deviate from this dual calling, no matter how irresistible the temptation of political activism. This reaffirmation of the humanist's solemn commitment to a set of values that transcends the burning political issues of the day contradicted the model of the intellectuel engagé popularized by Barzun's compatriots Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. It refined the argument in influential books by two other Frenchmen who had wrestled with the same question: Julien Benda's The Treason of the Intellectuals and Raymond Aron's The Opium of the Intellectuals. Barzun's admonitory remarks in his office and in his writings have guided me through political controversies in the academy ever since.

In later years I came to appreciate the connection between Barzun's clarity of vision in assessing the drama at Columbia in 1968, and the critical importance of clarity of expression and simplicity of language in academic writing. The proliferation of technical jargon in most learned professions has erected an impenetrable barrier between their members and the educated public. Barzun's own writings puncture the widespread and pernicious myth that opacity and complexity are the surest signs of erudition. By daring to delve into a wide range of disciplines without adopting the parochial mumbo jumbo that excludes all but the initiated, Barzun reminds us that the extreme specialization of knowledge in modern times need not prevent intelligent people from communicating with one another in a language all can understand.

A corollary to this restraint in language is Barzun's reluctance to inject the first-person singular into his writing. (A rare exception is the brief prefatory passage to The Energies of Art, with its fleeting allusion to his sitting at the feet of some of the pioneers of cultural modernism in his childhood home before the First World War.) This absence of self-referential prose seemed to me further evidence of the seriousness with which Barzun wrestled with his subjects, as if he did not want to distract readers by drawing undue attention to himself. Such a temperament is out of step with the self-promotion and self-advertising that has crept into much contemporary academic writing.

If Barzun's range of interests and insights was extraordinarily wide, it was hardly at the expense of mastery. The epithet dilettante, often hurled at those audacious individuals who cross disciplinary boundaries to poach on intellectual preserves far from their base of expertise, implies the absence of profundity. That Jacques Barzun is entirely innocent of such a charge was brought home to me in the course of coediting with Dora B. Weiner From Parnassus, a volume of essays in honor of his retirement from Columbia in the mid-1970s. The list of contributors to that volume reflected the high esteem in which Barzun was held by eminent experts in music, art, literature, detective fiction, philosophy, history, sociology, psychology, and science. This eclectic group of friends, colleagues, and associates had carried on a running conversation with him over the years about serious intellectual issues within each of their own fields. The respect and admiration for Barzun that they all expressed, both in their written contributions and in private communications, revealed how far his influence had reached. It is difficult to think of anyone with a more credible claim to the designation "Renaissance man."