In the opening scenes of Irene Taylor Brodsky’s documentary Hear and Now, the filmmaker juxtaposes home-movie images of herself as a smiling infant with a recording of her mother singing a vowel-drenched rendition of “Rock-A-Bye Baby.” Brodsky ’97JRN, in her narration, tells us that she was very young when she realized that her mother could not hear the songs she was singing.

Her parents, deaf since birth, had learned to speak as children in the 1940s. Their speech was far from perfect, and they used lipreading to understand what their children and others were saying. Then, in 2006, they decided to have an operation that would enable them to hear for the first time.

Hear and Now is the culmination of several films and a book that Brodsky has made on deafness. It was bought by HBO in 2006 and has won several honors, including the 2007 Audience Award at Sundance. In many ways it appeared to have put a chapter of Brodsky’s life behind her.

That is, until she discovered this past autumn that the songs she was singing to her own two-year-old son, Jonas, were not reaching him. “I’m supposed to be the expert on deafness,” she says, “but I don’t know if I’m going to be able to manage this.”

Brodsky, who is 37, has made documentaries on polygamy, architecture, and much in between, but deafness resurfaces at pivotal moments in her career. In Nepal, where Brodsky lived for four years after graduating from New York University in 1991, she produced a book of photographs of deaf people titled Buddhas in Disguise. “I was looking at a part of Nepalese culture that no one else had thought about,” she says. “How the Nepalese understand people with disabilities.” The publication of her book prompted UNICEF to commission her first film, Ishara, about deaf children in Nepal.

Brodsky returned to New York and earned a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia in 1997. After completing several television documentaries for HBO, the History Channel, and A&E, she landed an interview at CBS News Sunday Morning. At the interview she pitched a story about the photographer Mary Ellen Mark, but was told that CBS had just covered Mark, so Brodsky went with her back-up, the story of a deaf family in Rochester, New York, where she had been raised. CBS loved the idea and, although Brodsky never made that particular film, she went on to become a producer for Sunday Morning, creating more than a dozen short documentaries and winning an Emmy for her profile of the innovative rural architect Sambo Mockbee.

Jeffrey Tuchman, a filmmaker and former adjunct professor at the journalism school who has worked with Brodsky, says that it’s her connection to the people she films that sets her documentaries apart. “She is acutely aware of the characters and the stories in front of her,” he says. “She really sees and listens. What and how she shoots is intimately informed by that awareness.”

While most CBS producers turn their jobs into lifelong careers, Brodsky left after only two years, tired of the commercial grind and of living in a fifth-floor walk-up.

In 2002, her husband, Matthew Brodsky, a neurologist, was offered a job in Portland, Oregon. “It took me two days visiting Portland to decide, No problem. I’ll leave New York,” Brodsky says.

It was a risky move professionally, but Portland, with its vibrant community of artists, musicians, and filmmakers, offered her an opportunity to branch out and do more independent work. “CBS, I think, was the closest I ever came to traditional, objective journalism, and I appreciated it for that challenge,” she says. “However, the stories I’m more interested in telling are the ones in which I explore my subject’s perspective and even my own relationship with that.”

Getting Personal

Two years after Brodsky settled in Portland, an opportunity to make a personal feature film came unexpectedly her way. Visiting her parents in Rochester, she learned that they had decided to undergo operations to get cochlear implants. Brodsky was initially wary of their decision. She worried about what they would hear and how sound would affect their relationship after they had lived for so long in silence. But she also felt compelled to document her parents’ bold choice. Brodsky produced the film independently, raising money from friends. She spent two years making the film, which, in the end, turned out to be not a documentary about cochlear implants, but an intimate homage to her parents’ love for each other and a meditation on how the introduction of sound into their lives has altered the way they experience the world.

“What made Hear and Now so successful was that Brodsky was telling a profoundly human story and she was not derailed by the politics of deafness,” says Tuchman, referring to the controversy surrounding implants in the deaf community.

That’s not to say that Brodsky doesn’t have a political or social conscience. For the past year, she has been working on The Realm of the Final Inch, a documentary on the attempt to eradicate polio, specifically in countries like India and Afghanistan. The Realm is the first film project of Google.org, the philanthropic division of Google. It’s part of a growing movement dubbed “filmanthropy,” in which wealthy organizations and individuals commission filmmakers to make documentaries promoting their favorite causes. Traditional journalism, Brodsky says, might take issue with the idea of using a journalist as a tool to prompt social change, but she sees this trend as an extension of the socialfilm movement of the 1950s and 1960s that she studied and admired in school. “I was always drawn to the practitioners of cinéma vérité,” she says, naming filmmakers like the Maysles brothers, D.A. Pennebaker, Barbara Kopple, and her professor at NYU, George Stoney. Brodsky says Google placed no restrictions on her research or on her freedom to draw her own conclusions. “With Google I was really able to be a true journalist because I had the resources, the flexibility, and the freedom to go out into the remote regions of India to achieve the work,” she says.

In The Realm Brodsky follows a veiled Muslim social worker, named Munzareen, into the garbagestrewn alleyways of India’s worst slums in her search for the last unvaccinated babies in the country. “I could have followed her forever,” Brodsky says.

Two months after her return from filming in India, where she’d brought Jonas along, Brodsky learned that there might be something wrong with her son’s hearing. Jonas had been tested at birth and the doctors said he could hear. Brodsky was greatly relieved and didn’t worry when Jonas was late walking and talking. “So he wasn’t talking very much. I thought, He’s a boy and boys are a little delayed in those areas.”

Then, last August, at Jonas’s routine 18-month checkup at Oregon Health Sciences University, the teaching hospital where Matt works, the Brodskys were handed a prescription slip ordering an exam for Jonas in the auditory department of the hospital.

Brodsky was led into the testing room, given a chair, and told to hold Jonas in her lap. The audiologist played a series of tones that gradually grew louder and louder. Jonas didn’t respond to the sounds.

“They put the sound up to 90 decibels,” says Brodsky, “which is as loud as a subway train, and Jonas wasn’t doing anything, he wasn’t reacting. That’s when I first thought, Something is wrong.” Brodsky was crying when she called up Matt to tell him what was happening.

More exams followed, and this past autumn it was determined that Jonas was suffering from progressive hearing loss. (Although he can still hear some low frequencies, he is losing that ability as well.) Even then, Brodsky was startled when a nurse asked her if she knew about the Tucker- Maxon School across the Willamette River. “But that’s a school for deaf people,” Brodsky said. “Why are you asking me about that?”

Tears and Hope

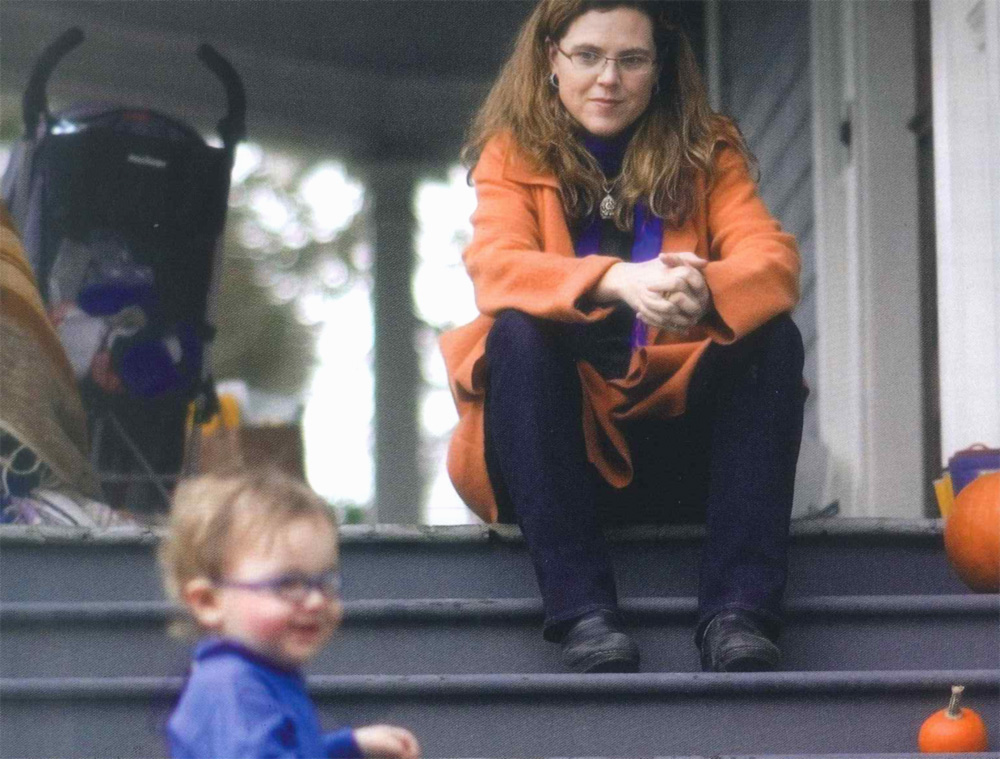

The Brodskys live in a large Victorian home high up on a hill above Portland. Nearby there are immense forests where Brodsky likes to hike. Coyotes sometimes come down and roam the neighborhood streets. Inside the house on this late December evening, the dogs bark as Jonas sits on the the livingroom floor playing with his toys near the piano that Matt gave his wife when Jonas was born.

“I look back at all my documentary projects on deaf people,” Brodsky says, “and I feel as if I didn’t know anything. All it took was being a parent to feel that I really see things. Everything has more resonance. Someone asked recently if I would make a film about my son. But I am emotionally incapable of doing that. I’m in the center of this maelstrom, and I don’t even know what it means. You need a certain amount of clarity to make a film, and I just don’t have that right now.”

In the living room, Jonas’s parents loudly repeat words to him. It recalls a scene in Hear and Now that takes place six months after Brodsky’s parents have received their cochlear implants. They sit on one side of a table while the doctor sits on the other side repeating familiar words with a screen held over his mouth so they can’t lip-read. Brodsky’s parents’ implants enabled them to hear sounds. But as much as they leaned forward and listened, they couldn’t understand what the sounds meant nor identify any of the words the doctor was saying.

The consequences of her parents’ operations have been mixed. Brodsky’s mother was emotionally overwhelmed by the surgery and confused by the new noises around her. Often she broke down in tears, frustrated by her inability to understand what she was hearing, while her husband’s comprehension continued to progress.

As the novelty of sound wore off, Brodsky’s parents often turned off their expensive hearing devices out of fatigue and frustration. “The CI is too much for me,” her mother says as she settles down with a magazine. “All day long. It wore me out.” It took over a year for her to be able to tolerate, on a calm day, the gentle sound of the wind or the waves breaking on the beach near the couple’s home.

The Brodskys hope that the few remaining frequencies that Jonas can hear now will help him learn to speak — and in the future, should he ever get an implant, he might better understand spoken words. “Right now I am trying to fill my son up with as much human language as possible,” Brodsky says. “I have to assume that tomorrow he will not be able to hear anything. He might even be deaf today.”

In the dining room, Matt lights the menorah and gives his son a present. It’s one of those plastic boards with animal buttons. Press the animal and it growls or whinnies or barks. Matt takes off the wrapping and opens the battery compartment.

“Why are you taking the batteries out?” Brodsky asks her husband with a start. “I’m not,” Matt says. “I’m putting them in.”