Justin Sarkar could use more time. Three o'clock becomes five, and suddenly he's late for an appointment. "I wish there were 36 hours in a day," he sighs. During college he needed extra time for exams, and barely made it through his last semester. Hours can go by before he pulls himself out of bed. A simple task like buying juice might lead him into a frustrating maze of indecision.

But on a bright, warm Monday in October, Sarkar '05CC stood calmly on the sidewalk at Broadway and 112th Street. Before him, lined up by the curb near Tom's Restaurant, were ten small tables made of green milk crates and wooden chessboards. This, for Sarkar, was where time ceased to exist.

"Chess is its own world," he says. "You play a serious, intense game, and for a while, nothing else in the world matters."

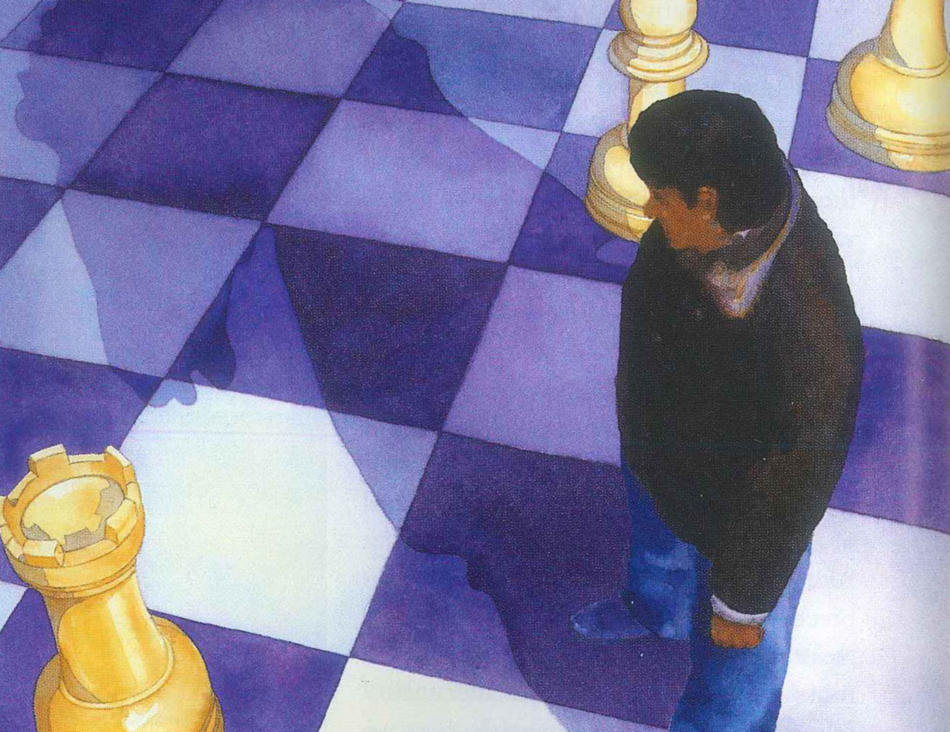

At each table sat a player of unknown ability, awaiting the chance to outwit Sarkar and gain some glory. Sarkar, of New Rochelle, is the New York State Chess Champion, a title he shares with Alex Lenderman, a 19-year-old from Brooklyn. Beat Sarkar and you'd be King of New York. Nearby, a sidewalk guitarist strummed Dylan and pedestrians stopped to bask in the carnival-like spectacle of the grappler who takes on all comers. This simultaneous exhibition ("simul" in chess speak), which included Columbia faculty and students, required Sarkar to have his mind inside ten games at once.

Dressed in beige chinos and an orange T-shirt bearing the words "New York Chess," Sarkar approached the first table and made minuscule adjustments to his pieces (he was playing white), touching them, arranging them just so before making his opening move. He repeated the ritual at each table.

Was it a nervous tic, this pregame touching? A psychological ploy? Or was it a way to assemble his thoughts, bring order to a complex mind?

For Sarkar is nothing if not complicated. A brilliant chess tactician (he majored in applied math) as well as a gifted writer (his e-mail missives about his games border on the Nabokovian), Sarkar has Asperger's syndrome, a condition whose traits of social awkwardness, acute self-consciousness, heightened sensitivity to stimuli, enhanced perception of patterns, and problems with attention and time management can create huge hurdles in life, including academic life.

"I can't think of when I was ever able to follow a lecture," Sarkar says in his soft, gentle voice. "I generally had enough will to get myself to class. My courses were really courses in survival: How can I survive?"

Somehow, he's been figuring it out. In 2001, at the age of 20, Sarkar became an International Master (IM), the highest title conferred in chess below Grandmaster. There are about 900 Grandmasters in the world.

"I seem to have an original approach to the game," says Sarkar, who first learned chess from his father at the age of nine. The two played until the father started losing ("He kind of gave up"). "I have my own system, but a large part of it is not having a system. A lack of studying has its price - it takes me a long time to make certain moves that shouldn't take that long for someone of my caliber."

That careful deliberation was on full display on Broadway as Sarkar went from table to table. Sometimes, after making a move and advancing to the next game, he would shift his hawklike eyes to the previous board and survey the pieces without expression. Then, after a few penetrating seconds, he'd slowly turn back to the game at hand.

"I can be thrown off balance by an unexpected move," he explains. "I think, 'Why didn't I properly assess?'"

This wavering of his attention caused some of the more optimistic players to imagine that Sarkar, taxed by the demands of ten separate games, might prove sufficiently distracted to lose at least one of them.

Little did they know just how much Sarkar had on his mind.

Four days earlier, Sarkar had spent the day with Russell Makofsky, the 23-year-old founder of NYC Chess, an organization devoted to the promotion of chess and chess education. (Makofsky's colleague at NYC Chess, bookseller and artist Adhemar Ahmad, can often be seen at Broadway and 112th playing chess with passersby.) NYC Chess was sponsoring the Sarkar simul, and Makofsky and Sarkar decided to head down to the Marshall Chess Club on West 10th Street to hand out flyers for the event.

Located in a grand old brownstone on a residential Village block, the Marshall is perhaps the holiest site in all of chessdom. Ascend a winding, carpeted staircase and enter a sanctuary lined with red vinyl benches and chess tables. The walls are crowded, Little Italy-style, with framed photographs of the greats: Mikhail Tal, Vasily Smyslov, Tigran Petrosian. A bust of club founder Frank Marshall, the U.S. Chess Champion from 1909 to 1936, sits on an antique cabinet between two high windows, and nearby is the famous Capablanca table, which was donated by one-time Columbia engineering student Jose Raul Capablanca, widely regarded as the greatest chess prodigy in history.

The president of the Marshall Chess Club is Dr. Frank Brady '76SOA, who taught English at Barnard for 25 years and is Bobby Fischer's biographer. Brady first met Justin Sarkar at the Marshall in 2001, during the tournament in which Sarkar graduated to IM. The two became friendly, and Sarkar occasionally sat in on Brady's classes at Barnard.

Brady, who often played against Fischer ("Don't ask me if I ever won"), has high praise for his fellow Columbian. "Justin will be a Grandmaster," he states flatly.

When Sarkar and Makofsky reached the Marshall, the participants in the club's Thursday Night Action Tournament were gathering. Looking around, Sarkar suddenly got anxious at the idea of coming here to hand out flyers for his own event. Did it seem arrogant? Presumptuous? What would people think? He considered signing up for the tournament in order to justify his presence, but was stopped by the unhappy thought of losing to a lesser-ranked player, which would damage his standing. (Action chess is played on a 30-minute clock - not Sarkar's strength.) "He had more to lose than to gain," Makofsky later said.

Finally, Sarkar decided not to play, but as soon as he got outside he was assailed by fresh doubts. 'I should have played," he fretted. That was when Makofsky suggested that they walk over to Washington Square Park.

If the Marshall is the high temple of the chess world, the southwest corner of Washington Square, with its cement chess tables and strewn newspapers, is the outdoor bazaar. Here, the gentleman's game is coarsened with trash talk and the slamming down of chessmen. Denizens, some of them homeless, beckon to onlookers for a game. Money has been known to change hands.

Sarkar had never visited this area, whose tinge of illegal street activity and wafting urine smells came up rudely against his fine-tuned fastidiousness.

"Hey, you lost?" a man called out from behind one of the tables, mistaking Sarkar for a curious amateur who had blundered upon the scene.

Makofsky quickly stepped in, and, with an impresario's flair, he arranged a five-dollar game between the man, a park fixture, and Sarkar, who was now feeling guilty about concealing his status as one of the top players in the country.

Sarkar put down his bag, which contained a new chess clock and some chess books, and sat. The man across from him lit a cigarette and spewed salty wisecracks, further irritating Sarkar, who was used to playing in silent, smoke-free environments.

After seven or eight moves, however, the man recognized what he was up against. His commentary faded.

"Piece by piece, move by move, Justin broke down his position," Makofsky recalled.

A crowd gathered, and Sarkar, pushing his pawns, promoted one of them to a queen. Game over.

"What are you, a 2300?" said the beaten man, inquiring into Sarkar's World Chess Federation rating. A 2200 is the threshold for an IM. Sarkar was at 2517.

"What are you?" Sarkar replied innocently. "A 1500?"

"Somewhere around there," said the man, who was a good deal stronger than that.

Makofsky refused the man's money, and instead tipped him two dollars. Everyone shook hands. Sarkar then looked down and saw that his bag was gone.

Stolen.

It was highly upsetting, this theft, but Sarkar could hardly afford to dwell on it. The next day, Friday, he was to begin a much-anticipated match at the Marshall with Alex Lenderman, his New York State co-titlist. Frank Brady had proposed the weekend-long contest as a way to unofficially settle the dispute of the shared title.

Perhaps the incident in the park had a galvanizing effect. Sarkar demolished Lenderman in the first three games, and offered him a quick draw in the fourth.

Then, on Monday, Sarkar traveled from New Rochelle, where he lives with his parents, to the simul in Morningside Heights.

Few at the exhibition knew what Sarkar had borne over the past days, to say nothing of his entire life.

"My confidence is very delicate," he says. "It seems to be hanging by a thread. It's very scary. If things are still intact, they are held together delicately."

But on this day, Sarkar moved methodically from table to table, betraying no sign of exhaustion or self-doubt. One by one, his challengers fell. Sarkar won every game.

Later, Sarkar was asked about his peculiar habit of fondling the chess pieces at the outset. He said he didn't recall doing it, but then he thought again.

A few weeks earlier, he said, he had witnessed a simul at the Harlem Children's Zone, wherein the featured player, a famous Grandmaster, touched all of his pieces before each of his 30 games.

Sarkar grinned shyly and brought out a worthy epitaph: "I saw Kasparov do it."