Watching A Time to Stir, Paul Cronin’s epic documentary about the Columbia student revolt of 1968, one is struck by a sense of the compression of time: What might have been seen 10 years ago as an interesting but socially irrelevant exercise in ’60s nostalgia, now, in 2008, strikes the viewer as alarmingly modern. It’s less déjà vu than plus ça change, but the effect is just as unsettling. We seem to be in two places at once.

This impression is heightened by several factors: the passion and energy of the former students, now in their 60s, as they reflect upon a moment that is still very much with them; the immediacy of the vibrant archival images, including long-unseen photographs, network television footage, and a stunning slice of film shot inside occupied Mathematics Hall by the English filmmaker Peter Whitehead; the virtually unchanged physical character of the Morningside campus, shown here in saturated brick-reds that bring instant recognition; familiar discussions about University expansion; a blossoming culture of drugs, music, fashion, and sexual freedom that has never disappeared; and, not least, the reemergence of deep moral and political divisions in our national life, fueled by an unpopular war (Abu Ghraib and waterboarding replacing secret bombings and napalm on the outrage meter), battles over illegal immigration, and a bitter distrust and suspicion of powerful institutions, both public and private.

Wisely, filmmaker Cronin avoids drawing comparisons between then and now, or, for that matter, pointing out the differences. Instead, he lets his articulate and voluble narrators — students, faculty, cops, activists — focus on what happened 40 years ago.

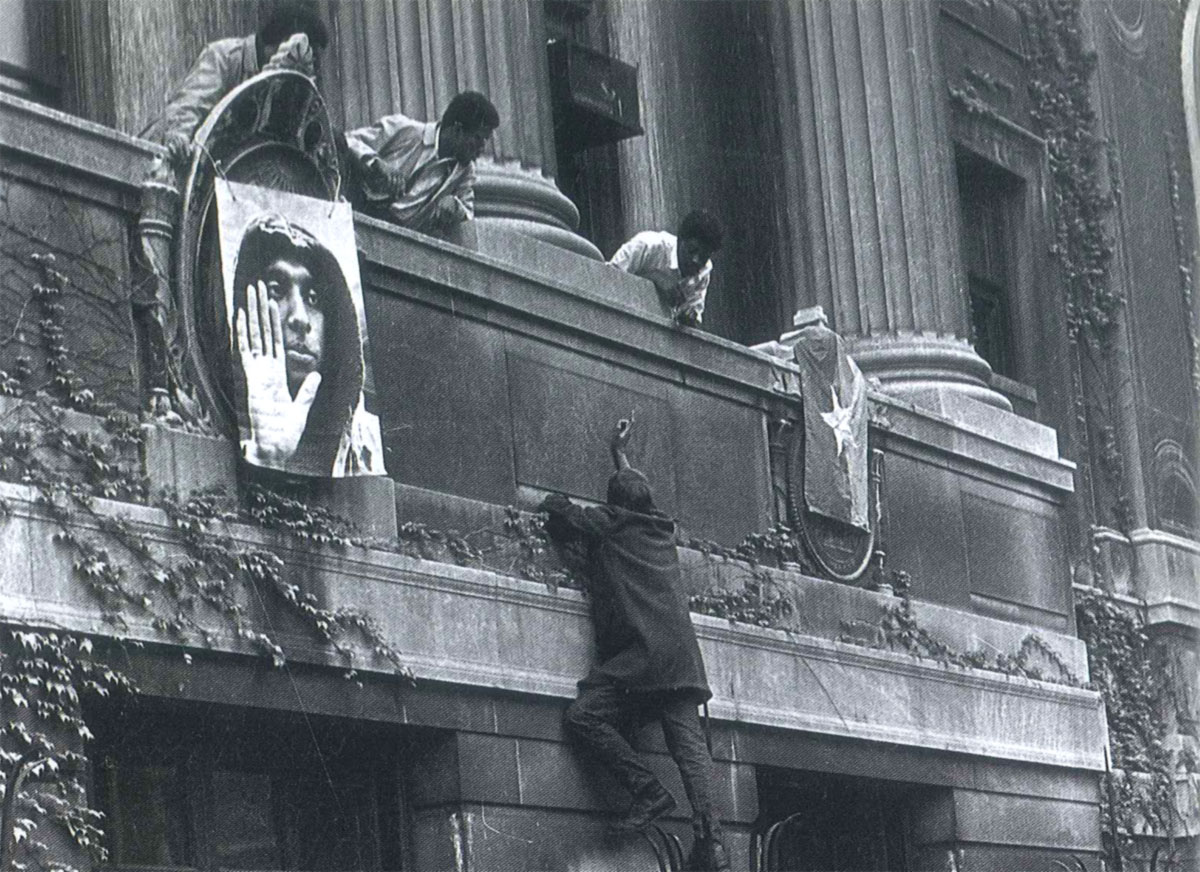

For those who missed it, here’s the basic plotline: March 27, 1968. More than 100 members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) enter Low Library to hand President Grayson Kirk a petition calling for the University to sever whatever ties it may have with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a U.S. military research group. The march violates a ban on indoor demonstrations, and six SDS members are placed on disciplinary probation. On April 23, a rally in support of the “IDA Six” is held at the Sundial. The demonstrators, numbering in the hundreds, try to enter Low Library, are rebuffed by security guards, and proceed instead to Morningside Park, where construction is under way on a Columbia gymnasium that will provide limited use and a separate entrance for the Harlem community. Some consider the gym a glaring symbol of the University’s disregard for its neighbors, and now, three weeks after the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the protesters, white and black, begin tearing down the fence around the excavation site. After a confrontation with police, the crowd returns to campus, and a decision is made to “liberate” Hamilton Hall. The students occupy the building and hold Dean Henry Coleman captive in his office. Representatives of SDS and the Student Afro-American Society (SAS) work together to hammer out a list of six demands. But the black students grow weary of the SDSers, whom they see as undisciplined and tactically naïve, and request that they vacate Hamilton and take a building of their own. The whites leave just before dawn and invade Low Library. Over the next six days, three more buildings are seized, and a complex web of negotiations among the student strikers, faculty, and the administration is conducted around the clock, against a backdrop of communal living, news cameras, angry football players, telegrams from Chairman Mao, folk songs, New Age nuptials, Black Power activists, rumors of guns, flying loaves of bread, and the hoof clops of the massing NYPD. And then comes the inevitable climax: an enormous bust and police riot that leaves scores of students and faculty injured and bloodied — and a good many of them radicalized.

Origins of a Revolution

Paul Cronin is a tall, 35-year-old Londoner with movie star looks and a cultivated five o’clock shadow who will pursue his Columbia ’68 studies at the J-school this fall. Perhaps conscious of his outsider’s perspective, he begins his movie with a quote from another Englishman, Thomas Paine, who inspired the American Revolution with his writings attacking the injustice of arbitrary authority, and urged action against tyranny: “When the country, into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears, it was time to stir. It was time for every man to stir.” That’s as far as Cronin goes in suggesting any historical analogs, but those who are tempted to see Grayson Kirk as King George III, or the Columbia students as the Patriots, have plenty to work with here. Kirk, with his thick-rimmed glasses and haughty professorial diction, comes off in TV interviews as a dated autocrat disconnected from sunlight and student affairs, while the young protesters seem to embody the “naïve but moving natural piety,” that philosopher Sidney Hook ’27GSAS ascribes to Paine in his introduction to The Essential Thomas Paine, published, with crisp timing, in 1969. But it’s the 1960s, not the 1760s, that concern Cronin, and he honors his subject by spending the first hour providing the social context from which the Columbia crisis emerged.

“Columbia ’68 is a microcosm of so many things,” Cronin says. “If you explain the context sufficiently, you’re telling the story not just of Columbia ’68, not just the new wave of antiwar, anti-imperialist protests in the late ’60s, not just how politics affects culture and vice versa; you are telling the story of a generation coming of age at an extraordinary time in America.”

Through pictures, newsreels, and interviews, Cronin gives an inkling of the psyche-shaping stimuli the college student of 1968 was absorbing during childhood and adolescence: high nuclear anxiety, the evils of segregation, Cold War politics, and, most significantly, the civil rights movement, with its televised images of people being beaten. “This is what defined, in our minds, the moral crisis in our country,” Ron Carver ’70CC tells us. “This is what defined who our heroes were.” Says former history student Laura Foner, “I would say to [student activists], ‘What got you involved in this? Why are you doing this?’ And they would almost all say, ‘I grew up believing in the promise of this country.’ And when they saw what was happening in the South, it was very powerful; people started questioning: ‘Is what I’ve been taught all my life really true?’”

Shattered idealism is one of the big themes of A Time to Stir, and this condition is raised to an intolerable pitch by the escalation of the Vietnam War in the mid-1960s, the specter of the military draft, and pictures on the evening news of bombing raids and dead Vietnamese. When Ted Kaptchuk ’68CC introduces himself by saying, “I’m the child of Holocaust survivors,” we know exactly where he’s going. “Seeing people being murdered. . .on TV was unbearable. I asked my father, ‘Why aren’t you in the street? Why aren’t you fighting this?’ And he had nothing to say. I was really despondent. I had to make that war end.”

Nick Freudenberg ’79PH (he was an undergrad in ’68), whose parents fled Nazi Germany, also is horrified by Vietnam, and speaks of the fear of being a “good German.” And black students, many of whom had suffered the injustices of Jim Crow laws, and who were now up against the more insidious forms of racism found in academia, have a similar response to the gym: It’s a racist enterprise, period, and must be stopped. As Freudenberg says: “We felt like we had to act.”

This absolutism, rooted in the students’ experience of persecution, becomes another one of the movie’s intellectual battlegrounds.

“The moral earnestness, the deep sincerity of those students, under terrible pressure — from the war, from the problems of racism, from the very serious moral issues involved in their exposure to conscripted service in the army in an unjust and cruel war, deeply moved me,” says sociology professor Allan Silver, a member of the ad hoc faculty committee that tried to mediate between the students and the administration and an exponent of the process-oriented, compromise-seeking liberalism so reviled by the radicals. “It’s tragic for me that those students followed the lead of a strike leadership that was not only indifferent to the University, but also actively hostile to it.” Of that leadership, Silver says, “As far as I was concerned — and I am far from alone in this — they were an enemy.”

Extremism in Defense of Liberty Is No Vice

“There’s no way I would have been inside those buildings,” says Paul Cronin, when asked what he would have done had he been there. “I have a pathological revulsion against joining groups.” This attitude might not have landed Cronin a date with Bernadine Dohrn, but in practice it is at least partially representative of the many students who, whatever their sympathies, just wanted to go to class and get an education. Operating from this inveterate neutrality, Cronin supplies a wide range of voices and opinions, and the triumph of his documentary is that there are no clear answers in the end. Complexity and nuance carry the day. “What makes a great tragedy is when both sides are right and both sides are wrong,” Cronin says. “It creates an extraordinary storytelling dynamic.”

This dynamic is especially compelling when the debate turns to the most controversial of the students’ six demands: amnesty from University discipline. The other ultimatums — that the University scrap its IDA contracts, halt the gym, lift the ban on indoor demonstrations, form a new judiciary composed of faculty and students, and use its influence to get charges dropped against those arrested in the protests — were at least negotiable in that they did not threaten, from the administration’s point of view, any fundamental moral standard.

But the call for amnesty was a brazen ante, if not a guaranteed nonstarter, and the arguments pro and con play like a great courtroom battle. Here’s an angry University vice president and provost David Truman in 1968: “The issue of amnesty is a lot bigger than Columbia. The question of whether a small minority of students may destroy an academic community and the means of its existence goes to the very heart of university and civilized life in the United States. We are not prepared to give on the point.”

Law professor Alan Westin, also in ’68, strikes a more hopeful note: “I believe [the students] will come to the conclusion that people who engage in acts of civil disobedience are impelled by their own ideology to accept responsibility for their own acts at points when the gains for their cause are measured against their responsibility for the laws of society.”

Westin was wrong, of course: The principles of Gandhi were not in vogue that season. Says Gus Reichbach ’70LAW, now a supreme court judge in New York: “If our demands were just and our actions forced upon us, there was no basis for punishment.” We are deep into the Core Curriculum here. Aristotelian ethics. Oedipal vengeance. These sons, whom Allan Silver calls “some of the most incandescently brilliant students I ever had,” were not about to pay for the sins of the father.

The fiery intelligence and self-possession of the students is well supported on screen. It’s a revelation to hear college kids speak out with such clarity and conviction. Whether you agree with them or not, there’s no denying that young men like SDS chairman Mark Rudd and SAS leader Ray Brown work the microphones with something more than aplomb. “We had a pretty good sense of how to handle ourselves under these circumstances,” Brown says of the black students, some of whom had helped organize antisegregation protests in the South. “We had really thought about this kind of event for years.” In one of the movie’s most gripping sequences, Brown and Rudd engage in a present-day cross-edited discussion of the fragile relationship between blacks and whites inside Hamilton, which broke down over, among other things, the question of whether to blockade the building (the SAS position) or keep it open to students for the purpose of radicalizing them (SDS).

“We didn’t know what was wrong with us, in a sense,” says Rudd. “We didn’t know why our participatory democracy was not acceptable to the black students. That was one of the things they cited — that our decision making was completely incompatible with the militancy that was necessary for that situation.”

“We made a decision that we were going to be disciplined,” says Brown, “and that no one would be injured if we had anything to say about it. We were committed to doing it in a disciplined way that we felt we could impose upon ourselves, but could not expect of others. And we thought our ability to be disciplined was encumbered by having white students who were irregular. There were all kinds of groups; they were smoking reefer and [doing] all kinds of things that we thought endangered what could be an important political moment.”

And Rudd: “You can probably say that I and the vast majority of SDS people had tears in our eyes as we left Hamilton Hall.”

Other SASers like Bill Sales ’66SIPA, ’91GSAS and Arnim Johnson ’71CC join Brown in casting their white counterparts as romantic revolutionaries whose flights of leftist political theory were a distraction from the very real and dangerous situation at hand. But Brown, who says that he liked the SDS people personally, saves his sharpest arrows for the historians and reporters who failed to give proper credit to the key role played by SAS. “It’s inconceivable,” he says sarcastically, “that a bunch of 80 or 90 black kids could have been the pivotal force that held together this event that affected thousands of people and brought this huge institution to its knees.” With the police reluctant to move in on Hamilton Hall, lest all of Harlem explode, the black student leadership found itself in a strong bargaining position, and negotiated, with their lawyers, a separate peace with the NYPD. In the end, the gym was nixed, and no billy clubs came down on any SAS skulls.

Hamilton Hall is of distinct importance to Cronin, who says he feels an “acute responsibility” to explore the “untold story” of the black students on campus that spring. “It’s an unfortunate verb, but the story of Columbia ’68 has been whitewashed. Hamilton Hall was the moral center of the whole protest,” Cronin says. “Another important part of the puzzle is the nascent women’s movement that started growing in strength that April, inside the buildings. All of this will require original historical research.”

Then there is the more familiar case of 21-year-old Ted Gold, the bespectacled, flannel-shirted son of Columbia instructors, seen delivering a statement to the media in defense of the protesters’ actions in a thick, syllable-stretching Upper West Side accent. He sounds perfectly reasoned and deliberate as he explains how the strikers had exhausted all procedural means of redress before occupying the buildings, and knowing his fate, one can’t help but wonder what is going on in his mind. Less than two years later, in March 1970, Gold would die in an explosion in a Greenwich Village town house, where he and other members of Weatherman, the extremist offshoot of SDS, had been preparing a bomb intended for an officers’ dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

Another of Cronin’s subjects, David Gilbert, is currently serving a life sentence for participating in a 1981 armored car robbery in which a Brink’s security guard and two police officers were killed. A pall of violence — committed and averted — hangs over the entire movie.

“If we would have gotten more power,” says Michael Steinlauf ’67CC, ’69GSAS, whose father survived the Warsaw Ghetto, “one of two things would have happened to me: I would have been murdered, or I would have become a murderer. There’s no question about that.” We believe him, and we know that he’s not the only one. This realization gives A Time to Stir a tinge of psychological horror, in which the monsters lurk in the minds of well-intentioned people on all sides of the issue. The horror is that they could be us.

Indeed, the psychic fallout of Columbia ’68 is not limited to those who lived through it; the wires are still live, charged with unresolved emotions and alternating philosophical currents, and they can burn anyone who touches them.

Paul Cronin knows this well. He calls making A Time to Stir “the most agonizing professional experience” of his life. “I have a very deep sense of responsibility to each side,” he explains. “That’s why it’s been so difficult. When you’re trying to tell everyone’s story, some people are going to be angry and disappointed.”

Cronin isn’t used to walking the minefields. His previous film projects have been about other filmmakers and cineasts: Alexander Mackendrick, Amos Vogel, Haskell Wexler, and Peter Whitehead. “It’s a very different beast,” Cronin says of A Time to Stir. “And it is a beast. People are very passionate about it, as they should be.”

Enter Peter Whitehead

In October 2006, Cronin attended the premiere of his movie In the Beginning Was the Image: Conversations with Peter Whitehead at the Vienna Film Festival. In the audience that evening was Todd Wider ’90PS, a plastic surgeon and movie producer in New York. After the screening, Wider approached Cronin about working together. (Wider tends to get involved with powerful, socially engaged projects. A recent one, the documentary Taxi to the Dark Side, about an Afghan cab driver’s beating death while in the custody of the U.S. Army, won the 2008 Academy Award for best documentary feature.) Cronin was already steeped in late ’60s cultural history through his documentaries on Haskell Wexler’s movie Medium Cool, whose fictional action merges with the actual protests that erupted in Chicago during the summer of 1968, and on Whitehead, who had chronicled swinging London and the Vietnam protest movement in America; so when Wider asked him if he had any ideas, Cronin barely hesitated: “How about Columbia ’68?” To which Wider replied, “How much do you need?”

And so Cronin, with Wider’s backing, set out on his journey into a deeply contested past. For a full year starting in February 2007, he went on a research bender, collecting boxes upon boxes of files, photocopying hundreds of documents, and tracking down anyone with a Columbia ’68 connection. He traveled to New York, Chicago, Boston, and California to film his subjects, and gradually amassed 11,000 photographs and 25 hours of archival film footage, and conducted 130 interviews. “This is a new visual representation of the era,” he says. “This is stuff that hasn’t really been seen before.”

The Peter Whitehead footage is the centerpiece. Cronin tells a story of how Whitehead happened to be in New York in April 1968 shooting The Fall, his Vietnam protest documentary, when he heard about the Columbia disturbances. Curious, he went up to Morningside Heights with his Éclair 16mm camera and a Nagra tape recorder. Looking to get into Mathematics through an open window, Whitehead encountered student Tom Hurwitz, who was seated on a windowsill in his capacity as a member of the Defense Committee. Whitehead explained that he was a countercultural filmmaker from England and not part of the hated “bourgeois press.” Hurwitz, a cinephile, huddled with his comrades, and Whitehead was let inside, where he proceeded to capture, in gorgeous, contrasty black and white, a unique look into student life inside the seized buildings.

Whitehead’s camera moves sensuously over the sleepless, waiflike faces of dozens of students, male and female, who are seated on the floor of a large classroom. These could be the beautiful nonactor models from a Bresson movie, and when they raise their hands to vote on a motion, Whitehead lingers on their limbs as if ranging over a field of delicate flowers. Addressing the students is New Left dean Tom Hayden, wearing a white shirt and dark tie and projecting some of the clean-cut, paternal mildness of his future father-in-law Henry Fonda. Then, later, a bandanna-clad Hurwitz, filled with egalitarian spirit, instructs his peers to clean up after themselves so that no one sleeps in filth. The mood is light, morale is high, but we feel the underlying tension, the guarded ecstasy of people who have broken through a wall. The young faces reflect the optimism of fortunate children; the blush of idealism, it appears, is still very much on them.

Cronin knew that the Whitehead footage was a keeper; the challenge now was to sift through the mountain of other material and structure a comprehensive and cohesive movie that people would want to watch. His strategy? “Keep it simple, stupid.” (Cronin has a master’s degree in criminal law from the London School of Economics, and knows how to construct an argument.)

The arduous editing process took place in a small, dark, paint-flaking room in the back of a West End Avenue town house owned by Todd Wider. The house had belonged to one of New York’s great subversives, Mae West, who went to jail for a week in 1925 on charges of indecency over her Broadway show, Sex. If ever a movie could be said to be the spiritual offspring of Thomas Paine and Mae West, A Time to Stir is probably it.

A Life’s Work

Paul Cronin would be the last person to say that he’s created a definitive record of Columbia ’68. He is aware of the endless layers of the story as well as the limits of his medium — he hopes to create a book to accompany the movie, as he’s done with other projects — and occasionally he expresses the frustration of one attempting to encompass the boundless. “This is just the beginning,” he’ll keep reminding you. “There is so much more to do.”

At nearly four hours long, A Time to Stir is, as Cronin hastens to point out, a work in progress. Cronin remains on the lookout for new voices and images from Columbia ’68, and he encourages anyone who was there to contact him.

In the final shot of A Time to Stir, we pause at a black-and-white photograph of Alma Mater, the grime on her head suggesting blood dripping from a crown of thorns. Draped across her chest is a banner that says, “Raped.” The rest of the message — “by the cops” — has been cropped out of the frame. It’s one of Cronin’s few explicit editorial interventions, meant to convey a notion of a broad attack on the University, perpetrated by multiple assailants.

This provocative piece of ambiguity is what brings us back to the beginning of the movie, and to Thomas Paine. For though Paine may be seen, from certain angles, as emblematic of the Columbia radicals, it’s hard to imagine that the man who inveighed against government and centralized authority would have hoisted the red flag above Mathematics. Then again, Paine was an ardent champion of the underclass who wrote, in The Rights of Man, “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.”

As with Columbia ’68 itself, and Cronin’s telling of it, we will uncover meaning where we choose to find it.