How Mozart’s Librettist Became the Father of Italian Studies at Columbia

One day in 1807, a fifty-eight-year-old man with hollow cheeks and deep-set eyes walked into the Isaac Riley & Co. bookstore at 123 Broadway. He was Lorenzo Da Ponte, a defrocked Italian priest who twenty years earlier had written the libretti to three Mozart operas — Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Così fan tutte. But gambling debts, love affairs, and politics had chased him from Europe, and in 1805 Da Ponte arrived in America, where he tried to support his family by opening a grocery in New Jersey. The store failed, and he opened another. It also failed.

Da Ponte had a special genius for doomed business ventures. He brought dozens of Italian books with him from overseas and ordered more in hopes of reselling them in his new country. This led him to Riley’s, “a famous importer of European books and a pillar of culture,” says Barbara Faedda, executive director of Columbia’s Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America and author of From Da Ponte to the Casa Italiana. When Da Ponte asked Riley if he had any Italian books, another customer, Clement Clarke Moore 1798CC, 1829HON, interjected that he could count the great Italian writers on one hand. “Lorenzo was offended,” says Faedda. “He said, ‘I could spend a month naming eminent Italian writers and poets.’”

The twenty-eight-year-old Moore, a biblical scholar who later gained fame for the poem known as “The Night Before Christmas,” was impressed by Da Ponte and introduced him to his father, the Right Reverend Benjamin Moore 1768KC, 1789HON, who was the president of Columbia College. Through the Moores, Da Ponte became a private Italian tutor for the offspring of elite New York families.

“He made friends with writers, painters, intellectuals,” says Faedda. “Everyone was aware that he had worked with the great Mozart and spent years in the best courts and opera houses in Europe. Lorenzo was a star.”

Da Ponte was born Emanuele Conegliano in a Jewish ghetto near Venice in 1749. His widowed father converted to Catholicism to remarry, and Emanuele, as was the custom, took the name of the converting bishop. To further his education, he became a priest, and after writing polemical poems against the ruling class — and fathering two children with his mistress — he was banished from Venice. Through the connections of a poet friend, Da Ponte, the witty, scholarly sensualist, became the librettist for the Italian theater company in Vienna. There he worked with Mozart as well as with Mozart’s archrival, Antonio Salieri. After Mozart died in 1791, Da Ponte’s chronic mishaps in amore and finance would send him fleeing across the sea.

In 1825, long after his European triumphs and travails, and after years of tutoring, Da Ponte, at seventy-six, became the first professor of Italian at Columbia. He was not salaried: students paid him directly, and registration fluctuated. It was another perceived slight for a man forever bemoaning the perfidies of an ungrateful world. But he never stopped promoting Italian culture, and he produced Don Giovanni in New York in 1826. “Lorenzo’s students were the only ones able to understand the Italian libretto,” says Faedda.

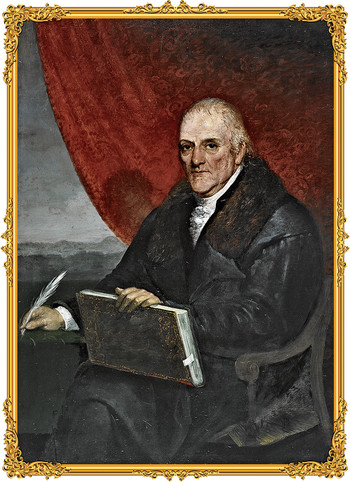

Desperate as always for cash, Da Ponte sold 264 books to Columbia. Seven of them, including works by Machiavelli, historian Angelo di Costanzo, and painter-poet Lorenzo Lippi, survive in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. And Da Ponte himself, who died in 1838 just shy of ninety, remains a Columbia presence. His portrait (by an unknown artist) hangs in the Casa Italiana, and in 1929 the Italian department created a Lorenzo Da Ponte chair, currently held by Dante scholar Teodolinda Barolini ’78GSAS.

This winter, the Mozart Week festival in Salzburg, Austria — Mozart’s birthplace — features a performance of Don Giovanni. Da Ponte may have based his tragic philanderer in part on his friend Casanova, but the character’s Act 2 utterance could be Da Ponte’s epitaph: Long live the women! Long live good wine! Forever may they sustain and exalt humanity!

For more on Da Ponte, listen to this episode of the Low Down.

This article appears in the Winter 2020-21 print issue of Columbia Magazine with the title "Lorenzo Da Ponte's Second Act."