Over the past quarter century, thousands of lawsuits have been filed against major American companies alleging that they knowingly harmed US citizens with products containing poisonous substances such as asbestos, lead, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). The litigation has forced the release of troves of internal corporate documents — material that could be of enormous use to public-health researchers, investigative journalists, and members of the public if only it were easily accessible.

Now a powerful resource at Columbia is bringing this material within reach. After years of gathering, scanning, and indexing records from across the country, public-

health scholars have built ToxicDocs, a growing database of some twenty million industry documents.

“It is the right of the public to know which industries knowingly profited from public-health hazards,” says David Rosner, the Ronald H. Lauterstein Professor of Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health and a professor in the history department.

The companies represented in the database range from small brake-parts manufacturers in Ohio and Michigan to multinational giants like DuPont, Johnson & Johnson, and Monsanto. The documents include internal memos, unpublished scientific studies, plans for public-relations campaigns, meeting minutes, and presentations — some dating back to the 1920s — all related to the introduction of new products and chemicals into workplaces and commerce.

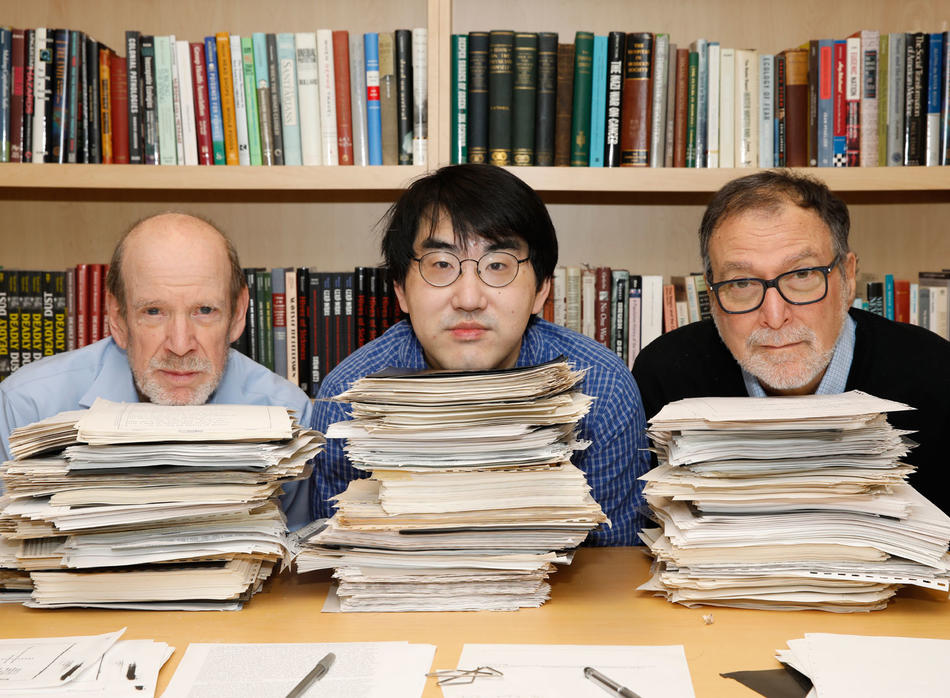

The ToxicDocs team is led by Rosner; Merlin Chowkwanyun ’05CC, the Donald H. Gemson Assistant Professor of Sociomedical Sciences; and Gerald Markowitz, a CUNY historian and an adjunct professor at the Mailman School.

Rosner and Markowitz have been collaborating since the 1980s, writing books about occupational and environmental disease and testifying as expert witnesses on behalf of plaintiffs exposed to industrial toxins. In the course of that work, they have accumulated boxes and boxes of company records.

“We’ve had access to millions of documents, but they were impossible to sift through,” says Rosner, who codirects the Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health at the Mailman School, which maintains ToxicDocs with the history department and CUNY.

Chowkwanyun is spearheading the effort to index and digitize the material and develop ToxicDocs’ searchable archive. With a recent $500,000 grant from the National Science Foundation — awarded through Columbia’s Data Science Institute — he is overseeing the development of software that will also help users detect subtle patterns in the data.

“ToxicDocs gives consumers, journalists, scientists, researchers, lawyers, policymakers, and community activists a strong, evidence-based tool for raising questions about industrial firms’ behavior,” says Chowkwanyun.