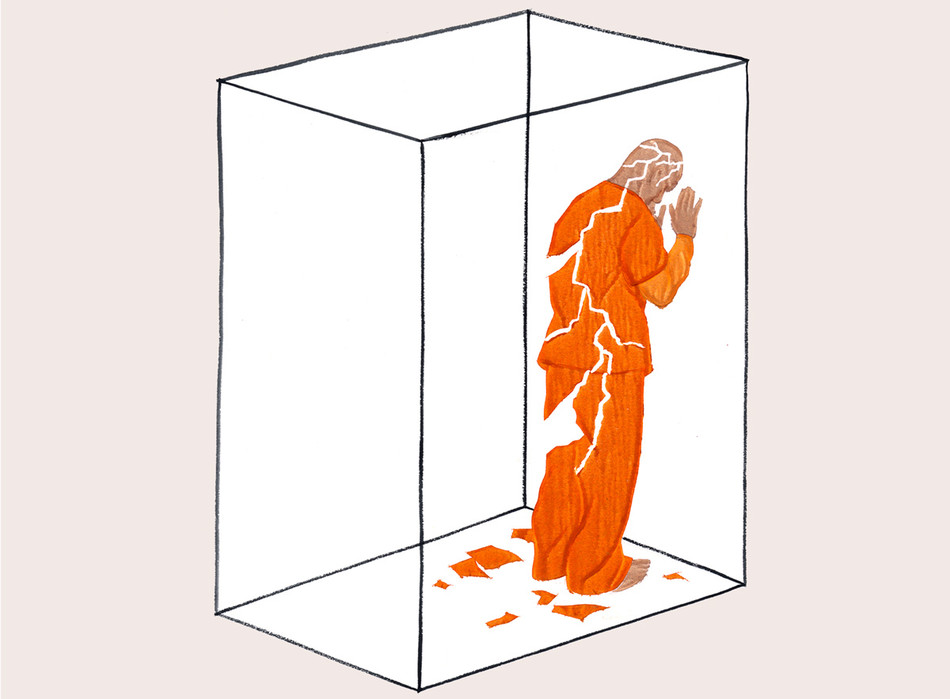

“You are just in a cell going crazy, hoping to sleep your day away, or eat,” says one man locked in solitary confinement at the state prison near Graterford, Pennsylvania. Another tells his interviewer: “I sit on the bed and do absolutely nothing … I’m not going to lie to you, I feel abandoned and alone at the same time.”

Known colloquially as “the hole” and euphemistically as “segregated housing,” “restrictive housing,” or “special housing,” solitary confinement is a form of punishment in which people are locked in parking-space-sized cells twenty-three hours a day, with no meaningful human contact for weeks, months, years, or decades. Prison officials call the practice a necessary tool for safety. Reformers call it inhumane.

In 2017, researchers from Columbia’s Justice Lab, a group of scholars dedicated to fighting mass incarceration and advocating for better conditions in American prisons, launched one of the largest studies ever of solitary confinement. Led by founder and director Bruce Western, the chair of Columbia’s sociology department, the team spoke with more than a hundred incarcerated men during and after their time in solitary. They also obtained twelve years of administrative records from the entire Pennsylvania Department of Corrections.

With this unprecedented access, Justice Lab researchers have now published three papers covering different aspects of solitary confinement, including its physical and mental toll, its relation to prison overcrowding, and its role in the social dynamics of prison life. The study also investigates racial disparities in the punishment. One startling finding is that 11 percent of all Black men in Pennsylvania born between 1986 and 1989 had spent time in solitary confinement by age thirty-two.

“We found strong evidence of psychological distress as well as a lot of material hardship, including hunger, exposure to extreme heat or cold, and sleeplessness,” says Western, who is the co-principal investigator of the study with Jessica Simes, an associate research scholar at the Justice Lab and a sociology professor at Boston University. The corrections-department records showed that the median time that people spend in solitary in Pennsylvania is thirty days. This despite the UN’s Nelson Mandela Rules for the treatment of prisoners, which, as Simes notes, prohibit solitary except in the most extreme cases and consider more than fifteen consecutive days a form of torture.

“My enduring impression is of an incredible, almost impossible-to-capture experience of deprivation and harm,” says Kendra Bradner, director of the Justice Lab’s project on probation and parole reform, who along with Western and Simes conducted the cellblock interviews.

Originally devised by Pennsylvania Quakers to bring the isolated, self-reflecting offender to penitence, solitary confinement was instituted in 1829 at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, famously visited in 1842 by Charles Dickens, who found the technique “cruel and wrong” and described the typical victim as “a man buried alive.” With evidence linking solitary to mental breakdowns and suicide, the practice faded from use, but it reemerged in the 1980s with the rise of mass incarceration (the US, which represents 4.2 percent of the global population, now holds nearly 20 percent of the world’s prisoners). The apotheosis of the revival was the 1990s explosion of “supermax” prisons — facilities made up entirely of solitary-confinement cells — and the use of solitary continues today as a means to punish a variety of behaviors and to control the prison population generally.

Yet for all the horrors of solitary confinement, the physical safety of corrections officers is also a constant concern, and the Justice Lab interviewed twenty-two prison guards to get a fuller understanding of the conditions confronting the staff. Western says that there are other ways to ensure staff safety and points to the absence of American-style solitary in other liberal democracies. “I’ve visited European prisons where the solitary-confinement units are empty,” Western says. “We use solitary for weeks and months, while Europeans use it for three or four hours to cool people off. That tells me we could be doing something very different.”

Justice Lab senior fellow Vincent Schiraldi sees present-day solitary as a natural outgrowth of our polarized politics. “When you have public policy based on the kind of anger and punitive sentiment that we had with mass incarceration, it’s not surprising that our facilities got meaner,” says Schiraldi, a senior researcher in the School of Social Work who has been head of juvenile corrections for Washington, DC, and commissioner of the New York City department of corrections under Bill de Blasio ’87SIPA. Both the inmates and the guards “have absolutely legitimate concerns, but they’re not interested in hearing from each other,” he says. “Either you ‘hate’ the guards and ‘love’ the inmates or vice versa. That’s a big problem.”

In the face of intractable bureaucracies and political inaction, the Justice Lab has been sharing its findings with prison officials, many of whom came up “walking the tier” as corrections officers and who insist they need solitary confinement to protect themselves and everyone else. “We’re trying to provoke a conversation among these guys, and the response varies,” says Western. “Some people are very open to this, but they want to understand what they could do differently.”

The great challenge for reformers, then, is to find alternatives that reduce the harms caused by solitary while being responsive to the concerns of staff.

“How we treat our prisoners speaks to how we respond to human frailty and vulnerability and marginality, and that spills over into all our social policymaking,” says Simes. “We need to find common understanding that prisons are meant to remove people’s liberty — not their health or their humanity.”