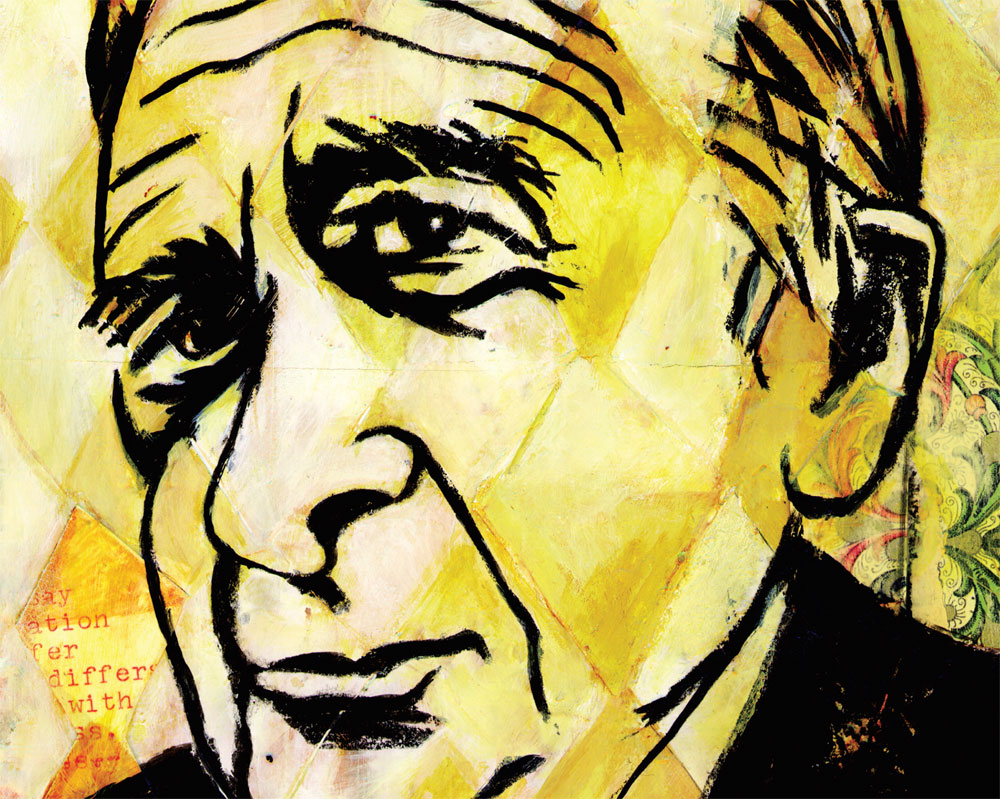

Most Columbia graduates have heard of Lionel Trilling, even if they have never opened his Matthew Arnold (1939), his E. M. Forster (1943), or his better-known collections, such as The Liberal Imagination (1950) and Sincerity and Authenticity (1972). Trilling ’25CC, ’38GSAS was one of the most influential literary critics of the mid-twentieth century. He was a public intellectual interested in shaping the tastes of educated readers, yet also an intensely local figure identified with New York, where he was born and raised, and with Columbia, where he received his degrees and, as the first Jewish faculty member of the English department, taught from 1927 until 1974. One of the New York Intellectuals, Trilling wrote for Partisan Review and served on its editorial board. When in The Liberal Imagination Trilling extolled Hawthorne’s ability to “dissent from the orthodoxies of dissent” and described classic American writers as embodying “both the yes and no of their culture,” he was reclaiming them for postwar modernity as tragic, complex ironists. Being of two minds about a subject, entertaining paradox and contradiction, braving complexity rather than clutching at simple (read “ideological”) solutions became Trilling’s own rhetorical signature.

The Middle of the Journey (1947) was the only novel Trilling published; nevertheless, he saw himself primarily as a creative writer rather than a literary critic. Several years ago, while researching Trilling’s relationship to anti-Stalinism, I discovered that he had worked for years on a second novel before finally shelving it in the early 1950s. The manuscript and his notes had been sitting among unsorted materials in the Trilling papers in Butler Library. The narrative attests to Trilling’s creative ambitions, but the silence that followed is more ambiguous. He may have lost faith in the novel, or he may have intended to return to it.

The untitled work — which I named The Journey Abandoned — was to have been a leisurely novel of manners in the great tradition of the bildungsroman; its subject was the life of letters in America.

The central consciousness of the unfinished novel, Vincent Hammell, is a young, untried literary man from the provinces. He has been chosen as the official biographer of Jorris Buxton, an elderly polymath who abandoned a literary career in his forties to become a prominent mathematical physicist. The Svengali able to appoint Vincent is Harold Outram, director of the Peck Foundation, “with power to dispense at discretion those incalculable millions for the advancement of American culture.” As a young writer, Outram had been drawn to the Communist Party and proletarian aesthetics, rejected both, suffered a nervous breakdown, and finally rebounded as a popular journalist before being appointed to his current position. The young, ambitious Hammell and the brilliant, compromised, and barely stable Outram represent different stages and different ways of living the literary life. Vincent’s undergraduate mentor, Teddy Kramer, offers another, though hardly tenable, model: the professional scholar so comprehensive and scrupulous that he can never complete his opus.

In the excerpt that follows, Vincent Hammell, who has sought out and is about to meet Harold Outram, visits Teddy Kramer, his former professor.

Geraldine Murphy ’85GSAS is associate professor of English and deputy dean of humanities and arts at City College, CUNY. She edited and wrote the introduction to The Journey Abandoned.

From Lionel Trilling’s The Journey Abandoned

Kramer’s little Jewish face broke into its tentative smile. Vincent knew how much Kramer loved to be teased and how much he loved to be reminded that life might be careless. As best he could, Kramer broke through his magisterial gravity to meet the joke. He nodded his head in an owlish parody of himself. “Well, now, we must try to straighten this out, Mr. Hammell,” he said elaborately, “we must look into this.” He was being Professor Kramer, the careful, sympathetic teacher. An unkind observer would have found matter for satire even in his self-mockery.

Vincent was a little restored by Kramer’s pleasure in the joke. Today or any day, Kramer too would be working his own way through darkness. But with how slim a chance for success. In a few minutes he would stalk into his classroom, a small man, stiffly and meticulously dressed, timid, suspicious, but resistant. He would lecture on the literature of modern Europe as he had learned to love it in his rebellious youth, arranging into careful categories the lessons of rebellion to be found in Ibsen, Sudermann, Schnitzler, Wassermann and Pirandello, referring to his careful notes in many languages, which actually included the Scandinavian. As he talked, his stature would grow and he would forget his old-fashioned Jewish pride, which Vincent had come to see as consisting of the belief that being Jewish meant being a physically small man of such scrupulous intellectual honesty that he could bring no work to a satisfactory conclusion. Before his mind Kramer kept forever the martyrdom of the artist and the seeker for truth. “Dedication” was the word he thought, “integrity” and “compromise” were the words he used.

Kramer said, “Vincent, you look tired.” His tone was admonitory, even querulous, and Vincent knew that in this way he expressed and masked the affection he was feeling.

“Do I?” The interest of his friend and former teacher made Vincent feel young and heroic. “I was working late last night.”

“On the book?” Kramer asked. “Is it going again?” He spoke in an almost hushed voice and Vincent knew that Kramer was seeing the lonely light in the little room and was hearing the intermitted rattle of the typewriter. He knew that Kramer was having a vision of his young friend “wrestling” with his work, for only in this way could Kramer imagine the process of thought and creation.

At this moment Kramer would have liked to say that no idea of material gain, no glimpse of mere popular success must intrude to spoil the purity of the work. He wanted to utter his belief that Vincent’s long months of sterility and despair were the marks of the virtue of his enterprise.

He did not say what he believed, but his feminine solicitude shone from his face. All he said was, “I’m glad you’ve broken through again. That’s bound to happen — the ideas find their place.”

Then, shy of what he was about to say and making his manner objective to the point of dullness, Kramer said, “I’ve been thinking, Vincent. Now that you’re in the clear — I didn’t want to interfere before — it occurs to me to suggest that sometimes such difficulties are not entirely intellectual. Often they are emotional — psychological, you know. They are often — ”

And Kramer looked straight and brave into Vincent’s eyes. “They are often sexual. You used to have a kind of affair, as I remember, with a little undergraduate girl. But I gather that lately — What I mean, of course, is not marriage. I shouldn’t like that for you just yet, but a civilized — You know, a boy like you should have many triumphs in his campaigns.”

The old diction of love with its metaphors of warfare came easily to Kramer. He knew the long account of Goethe’s amours, which, to account for genius, the scholars have told over so often, and he could conscientiously suggest to Vincent a line of action which would have been [as] impossible to himself as cannibalism. But it was part of the tradition of his youth to war puritanism.

Vincent smiled, feeling a tender amusement at his awkward friend. He thought he was unperturbed by Kramer’s advice, yet he chose this moment to say, “I’m going to meet an old friend of yours.” Kramer noted that Vincent had refused the opening. He was of two minds about the sexual conduct of the Gentile world. On the one hand, he believed it licentious. On the other hand, he believed it hopelessly and symptomatically puritanical.

“An old friend?” and Kramer’s eyebrows went up in genuine surprise. “Who could that be?”

“Harold Outram,” Vincent said and heard in his voice not only the intention of surprising but also a certain readiness to be stubborn. He had supposed that the name would have a considerable effect on Theodore Kramer, but he had not imagined so deep a stirring as actually took place. Kramer’s little face went white and his eyes opened in an almost wild consternation. He seemed on the point of repeating the name incredulously. But then he said with a notable calm, almost a haughtiness, as if Vincent had committed a breach of etiquette which could be dealt with only by the grand manner, “And how, Vincent, did this come about?”

“Well,” Vincent said and knew at once that that “well” had spoiled his reply, “I wrote him a letter.”

“You wrote him a letter.” There was no question in Kramer’s voice. But the question came now, the more accusingly for the delay.

“Why?” Kramer asked.

Why indeed? He had, he thought, written on an impulse, on generous impulse. He had liked some essays written when the author had been not much older than he himself now was. He had sent a letter, really a very graceful letter, to tell the author of his admiration. It was a common enough thing to do, people did it every day. To be sure, one does not often write in appreciation of work done ten years ago. Still, even that was not so strange. What was perhaps worthy of remark in his action was that the author was no longer a fine writer but a man who had been a fine writer, ten years before. That could, of course, bring his letter into something like ambiguity, making its impulse at least not an ordinary impulse.

“‘Why?’” said Vincent, questioning the question.

But of course it was useless to pursue this line. He knew the answer. Apparently everyone else knew it before he did. He said, “I wrote to him because I read him and liked him. But you mean that I wrote for more reason than that. You mean that that ‘more reason’ wasn’t entirely innocent. That I had — ‘an ulterior motive.’ I think you’re right.”

He could not have said it with more simplicity. The moral fire in Kramer’s eye banked itself. It occurred to Vincent that, to account for so complete a confession, there must be, beneath his affectionate superiority to Kramer, a stronger trust than he had ever supposed.

“An ulterior motive,” said Kramer. He said it gently and sadly. He tasted each word drily, “Motive. Ulterior,” and shrugged as if he found them without any savor of meaning at all.

“Go see him, Vincent. You will learn something from him, I can assure you. You will see a man utterly corrupt. A handsome man, a charming man, and — I can guarantee — a man utterly untouched by life.”

Vincent said, “Untouched? I thought from what you’ve told me that he had a hard enough time.”

“Hard time? You mean he was a poor boy? Yes, technically I suppose he was. But when you have his looks and charm, you’re not poor, no, you’re by no means poor.” Vincent knew that Kramer was saying that Outram had not been a Jewish poor boy. “He worked his way through college but people took care that the path should be smooth for him. I’m sure you will see a man still young, untroubled. But let me tell you, Vincent, you will see a man utterly corrupt.”

Kramer’s voice rang with the passion of his bitterness. “Let it be a lesson to you, Vincent,” he said.

Embarrassed by the nakedness of his friend’s feeling, Vincent said in a worldly way, “It’s quite a lesson — at thirty thousand a year.” For that was the sum which, according to rumor, Outram received as director of the Peck Foundation.

But his irony did not lighten the situation at all. Kramer was fighting for souls, Vincent’s and his own. He was defending the dark castle of six small rooms which housed his virtuous wife, his two unruly children and the book that must never be finished.

He was defending something else as well. How many cups of coffee or glasses of beer he had drunk with Harold Outram at college was hard to calculate, because each cup of coffee or glass of beer provided Kramer with more than one memory and had been seen by him from more than one point of view. Kramer’s accounts of the early friendship varied according as he was bitterly proud or proudly bitter. Vincent, in his mind’s eye, saw the young Harold Outram bending his brilliant head toward the young Theodore Kramer, in the companionship, or its simulacrum, from which Kramer had not recovered. But never until this moment had Vincent understood how intense that variable memory was to his friend, how involving, passionate and enduring it was, or how torturing.

Kramer rebuked Vincent’s frivolity. “Quite a lesson,” he said with a large homiletic sadness, “yes, Vincent, quite a lesson. To have been Harold Outram, to have had his gifts, to take a doctorate at twenty-three, to write essays and a book like his — quite a lesson indeed. All right, Vincent, I am very intelligent, a good scholar, a very exact skeptical mind. And you are a very intelligent young man. I’ll say it: the best student I ever had, and you know the kind of hopes I have for you, the kind of work I expect you to do. But Vincent, let me tell you that the two of us together couldn’t touch Harold Outram when he was young.”

The pulpit tradition of Kramer’s childhood was not a good one, but the unconscious memory of all the rabbinical sermons he had once despised came to Kramer’s aid now. “The biggest lesson of all, I assure you, Vincent,” he said, wagging his head with sad wisdom, “the biggest lesson of all is what a few years can do, what life can do to a man. To give up such talents, to pervert and prostitute them! For what? For a contemptible few thousand dollars a year. Our money economy knows what it wants, believe me. It knows what it wants and it gets it. Our profit system knows how to buy the best. If the Peck Foundation wants a commissar of culture it buys itself a Harold Outram — after he is corrupted by that magazine he worked for! Such a magazine! At fifty thousand a year — is that what he gets? — he coordinates culture in America. A grant here, a grant there, could such an artist and scholar go wrong?”

Then, getting down to business, he said briskly, “You think he can help you, Vincent? You think one of those grants could be for you?”

“Oh, come on now, Ted,” Vincent said, with an expansive and worldly note of protest, “aren’t you letting this thing run away with you? After all, I only wrote the man a letter. He invited me to come to see him — I never suggested it. And you know that the Peck Foundation only puts its money into institutions.”

Kramer dismissed the practical objection. “A man like that has the power to help anybody. You ought to know that money isn’t everything in things like that. He has what’s better than money — he has power.” Then he said as if standing back from the situation, as if he understood that in this world there are many things one must do to survive, “Vincent, I don’t blame you. Maybe you are wise.” But he could not play the part for long. “For God’s sake, Vincent — you are trying to act as if you didn’t understand. After all, I am talking to the man who wrote ‘The Sociology of the Written Word.’”

Kramer was appealing to the best of Vincent, appealing from young Vincent Hammell caught in the dream of the great world to young Vincent Hammell seeing deep and clear, with all his wits about him, into the modern situation. He was conjuring his young friend by recalling to him his own true words. Vincent’s essay with the pretentious title had appeared in The Prairie Review and nothing that Vincent had ever done had won Kramer’s blessing so completely. And indeed it was the best thing that Vincent had ever written, the most elaborate and the most mature, and quite the freest, for it had been touched with wit, a long and rather desperate examination of the various perils which beset the young man who gives himself to the life of the mind.

Vincent had been proud of this essay and Kramer and his younger friends had quite justified his pride by their praise. But now the piece seemed youthful and priggish and Kramer’s appeal to it was not effective. “I’ve got to get away from here,” he said. He felt dull and miserable and confused. All the sprightliness that Kramer so often aroused in him was gone. He used the sentence he had earlier spoken to his mother. “I can’t go on like this,” he said. He made a gesture to indicate the environment as far as the mind could reach, and Kramer needed no explanation beyond this to understand that Vincent was referring to this great rich city with its busy life and its great emptiness. For Kramer himself this had become the right — or the inevitable — setting for all the things of his life, his family, his home, his work and his fears. But he was a scholar of rebellion, of the free and developing spirit, and he knew what Vincent felt.

Kramer looked at his young friend with intent shrewdness. “Vincent,” he said, “if you were appointed to a full-time instructorship, would you stay?”

The question, which implied that the instructorship was actually available, was shocking to Vincent. Perhaps it was the more shocking because it was crammed full of attractions, even temptations, all the prosaic charms of a settled position, not notable but surely comfortable, and of a settled salary, not large but regular. It meant to him the giving up of all his hopes and that was its charm. He saw the gentle sad pleasure of acquiescence to the family wish. His parents could scarcely be so deceived as to be overjoyed by such a position, yet a son with two thousand dollars a year would make the difference between worry and comfort. Vincent saw stretching before him, and not with the usual horror, the long days of serviceable piety. Everything that he feared for himself and that Kramer had feared for him had a sudden strange lure.

But he saved himself. He thought of what was implied about Kramer by Kramer’s offer. He said coldly, “I thought you didn’t approve of my taking a job at the university. When I wanted one two years ago, you talked me out of it. I thought you couldn’t do anything for me in the department beyond my assistantship. You’ve told me that often enough, and now you seem to be making me an offer.”

Under this almost direct accusation of insincerity, Kramer did not flinch. “As for doing anything for you in the department,” he said, “anything I do for you, Vincent, will be done at a certain cost to myself. You know what my position is. It is not good. But I am willing to put what position I have to the test. I am ready to endanger myself.”

Vincent found that he was suddenly impatient of Kramer’s extravagant sense of vulnerability. He had accepted it at Kramer’s own estimate and it had been a kind of bond between them. Kramer and he shared the sense of danger that made heroes. But now he saw that the good Kramer, although by no means the most powerful of professors, was no more insecure in his position than anyone else. It was the insight of anger. He checked himself — he had felt anger too often that day.

“I have always,” Kramer said, “I have always been opposed to an academic career for you. It is not in your temperament. I am one of those who teach, you are one of those who can do.” And as Kramer made the old stale antithesis that had been so fresh when Bernard Shaw had made it in Kramer’s boyhood, Vincent had a moment of sadness for his teacher. “But, Vincent, I am even ready to see you make a possible sacrifice of your talents by taking a regular appointment here. Maybe you even can make a future. I am ready for anything rather than see you involve yourself with Harold Outram. You say you can’t go on like this. All right. Admitted. Granted. But when you go on to something different by the help of Harold Outram then — no! Anything else.”

Kramer kept his eyes fixed on Vincent’s face. He was very stern and direct. It seemed to Vincent that his friend had never had so much dignity as was now lent him by his passion. “Anything,” Kramer said. And again, “Anything.”

He went on. “Vincent, I know you do not want to become what I am. I know — ” He held up his hand to check Vincent’s stricken protestations. “And why should you? I’m stuck — I’m a Jew, I’m a married man, with children. I’m stuck. But leaving money out of account, you have every advantage. You can be something and not be corrupt. But that man, if you let him, that man will corrupt you — corrupt you to Hell.”

It was nonsense. Yet whatever in Kramer was ridiculous had quite vanished. Vincent heard him almost with awe and wholly without an answer.

At that moment the bell rang for the beginning of the next hour. Kramer selected three books from the row across his desk. He piled them neatly on the folder that contained his lecture notes. He rose. When he was at the door, he smiled a wan and intelligent smile which was very charming, for his teeth were fine and white. He said, “Perhaps, Vincent, I am only jealous.” He smiled again, almost with a touch of saving mischievousness, and then he was gone, leaving in the air a large reverberation of meaning.

For a moment it seemed to Vincent that something had been explained. But then he found that he was not at all clear about the object of Kramer’s confessed jealousy. Was it Outram that Kramer was jealous of? Was it perhaps Vincent himself? Was it conceivably Vincent in his connection with Outram? Or Outram in his connection with Vincent? He could not tell, but jealousy implied the estimate of value, of store set upon something. And as he walked to his luncheon appointment with Outram, it seemed to him that what Kramer had expressed was not an evaluation of Vincent’s youthful advantages or of Outram’s power. No one could be more precise in his use of language than Kramer, and he would have said envy if he had meant it. Jealousy meant that Kramer had in mind the connection that might develop between his two friends. It was love that Kramer had been thinking of rather than power, and to exist with Outram in Kramer’s emotion gave Vincent a kind of parity with the man he had not yet seen. He felt an excitement which he thought of as confidence.

It stood him in good stead, this confidence, for Outram had appointed the Athletic Club as their place of meeting. He was staying at the Club, which of course quite became his position, and the Athletic Club at lunch hour was quite different from the Tennis Club of the morning.

The Tennis Club was, at best, gentility — that is, status without power — and even its gentility was lately being somewhat eroded. But the Athletic Club was the power that made status. It proclaimed its nature in the largeness of all its furnishings, in the solidity of the walnut that paneled its walls and the permanence of the leather that covered its armchairs, in the very darkness of the great lobby, in the smell of the bar that was just off the lobby. Vincent felt sure that no club in New York or even London could better give the feeling of massed masculine force. One of Kramer’s stories about Harold Outram had for its occasion a drink at the Harvard Club, and Kramer had been annoyed at Vincent’s quick foolish cry, “What does it look like — the Harvard Club?” Yet, as of course Kramer sensibly saw, a young man with Vincent’s work to do would naturally have a sociological interest in any number of things, in settings or ways of life or manners that he would not necessarily approve of. Vincent and his friends liked to think. Or these were the scientists of the great plants with their rather dry but not unfriendly looks [sic]. Had anyone at any other time said to Vincent Hammell that reality was made here, he would have loftily resisted the idea. But now he felt it to be true, and he braced himself against the fact, feeling impalpable.

He really did not know how to think about power. His mind turned to the appearance of the men about him. Here, if one saw tweeds, they were not the heavy stiff harsh tweeds that members of the university wore. And actually what one saw most were dark, softly hanging cloths, distinguished from each other only by differences of pattern of the subtlest kind. Vincent had reason to be glad that instinct had taught him that if one must dress cheaply one did best with suits of grey flannel, with shirts of white oxford, with ties of the simplest stripe — they were far harder to find than might be supposed — and with sturdy, but not extravagantly sturdy, shoes. He despised himself for being aware of his propriety, but he could not help it. He comforted himself with the thought that such matters had not seemed trivial to Balzac and Stendhal, from whom he had learned the name of Straub, the great tailor of the Restoration, although be could not have named the tailor that made these men around him so beautifully unnoticeable.

It was a small and frivolous mind that could be aware of appearance when so much reality was all about him: he was sure of that. These men made the things and decisions that affected the lives at least of thousands, perhaps of millions. That was power, that was the creation of reality. But he could not conceive the joy of that. All that he wanted was the license to move freely and without embarrassment in the world, to be swift and simple and a little touched with glory.

From Lionel Trilling’s The Journey Abandoned: The Unfinished Novel, Geraldine Murphy, editor. Published by Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2008 James Trilling.