In the first car of a subway train, a bearded, middle-aged man stands pressed against the front window. He holds a camera to his eye, lens to the glass, waiting for his quarry to come into view. Then he sees it ahead, coming closer: a subway platform. Empty even at rush hour, it’s in an abandoned station — a “ghost station,” as they’re called. As the train passes through, the man snaps off several shots. The murk of subway tunnels hardly makes for ideal conditions, but Joseph Brennan ’73CC, ’82LS knows how to take photographs in dim light.

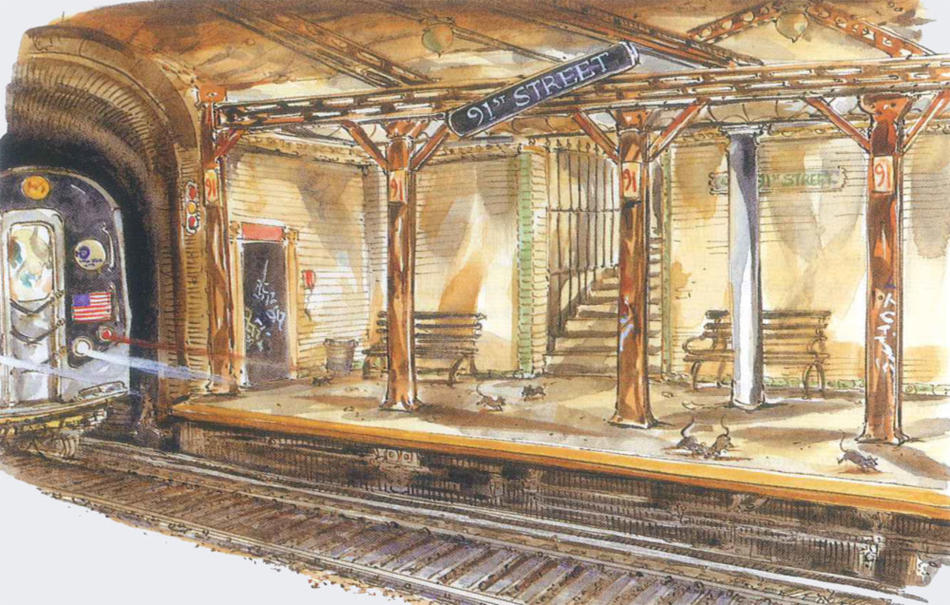

Brennan has been stalking these phantom stations for the better part of a decade. Columbians might be familiar with the one at 91st Street and Broadway, a graffiti-filled shell visible from the 1 train. There’s an especially grand and ornate ghost station underneath City Hall, and very occasionally the Transit Museum will take visitors on a special tour of it. Nearby is the abandoned Worth Street station, which closed in 1962.

After extensive research, conducted mostly in 2001, Brennan developed a series of Web pages devoted to these and other ghost stations, posting lengthy descriptions along with historical photographs, maps, and track plans. A genial guy, Brennan displays easy familiarity with numerous aspects of the subway system, from variations in routes to nomenclature like IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit) that you hear from New Yorkers of a certain age.

Brennan started riding the subways as a high school student who commuted to Fordham Prep, in the Bronx, from his home in Rockland County. He continued to ride as a college student in the early ’70s, when the trains were covered in graffiti and sensible people didn’t relish riding alone after dark. After graduating, Brennan joined the University’s library staff, working at Butler for a number of years and picking up a master’s degree from the School of Library Service — and more train time — along the way.

During a commute several years ago, Brennan looked out the window and realized he was passing through a ghost station. The sight of it fired his imagination, and he decided to learn more. He visited libraries and consulted historical maps, newspaper articles, photographs, subway timetables. He read about the construction of the system’s different lines, identified when stations had been in use and when they ended service. He resolved to ride the subway — the whole darned thing, all 722 miles of it — to see which platforms might still be visible. He found that at some stations, he could catch a glimpse just by keeping a sharp eye out. In others, he discovered a visible door that he knew led downstairs, to a parallel line no longer in regular use.

As it happened, Brennan left the libraries in 1989 to join the precursor to Columbia University Information Technology (CUIT), and among other things helped introduce e-mail at Columbia in the early ’90s. (He gave presentations explaining why it might be a useful thing to have around.) He’s now been the University’s lead systems engineer for e-mail for several years — looking after servers, managing spam filters, solving complicated user problems. So Brennan knows his way around a computer, too. Those skills came in handy when he decided to post his subway findings on the Internet.

Once the material hit the Web, Brennan was contacted by all sorts of other subway enthusiasts — people who corrected his mistakes or had something to contribute, like the pictures of an abandoned PATH station sent by a Port Authority contractor.

Abandoned stations tend to stay that way, but they’re not completely static. Sometimes a platform is temporarily closed, or opened, or a construction project reveals some new facet of the system and its stations. Indeed, Brennan says, it might be time to update his research. So if you’re riding the subway and you happen to see a bearded man plastered against the front window with a camera to his eye, try not to distract him. He’s just tracking down a ghost.