In 1908, Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World and future benefactor of Columbia’s journalism school, stood before the New York World Building in Lower Manhattan and looked up at the immense stained-glass window that had just been installed above the entrance. The window shone in blues, greens, yellows, and purples, with a tiny flame tip of orange, and depicted a female figure with whom Pulitzer was more than casually acquainted.

Pulitzer had reason to admire this lady’s likeness, even if the real thing could be glimpsed from his private office in the dome of the World Building — all 151 feet of her out there in the harbor, her copper skin already oxidized to green. Where would she be, if not for Pulitzer? And where would he, an immigrant from Hungary, be, if not for the ideals she embodied?

Yet in the early 1880s, the statue’s home was in doubt: work on her pedestal had been suspended, and without an additional $100,000, some other city might well have taken possession of France’s 225-ton gift to America.

Pulitzer decided to use the World to help. In May 1883, he ensconced the Statue of Liberty — a peacock fan of sun rays behind her, her pedestal flanked by the two hemispheres resting on a bed of clouds — on the World’s banner, replacing the paper’s former logo (two hemispheres and a ray-emitting printing press), which Pulitzer had created when he took over the paper earlier that year. Then, in 1885, he wrote in an editorial that it would be “an irrevocable disgrace” if the funds for the statue were not raised and promised his readers that the name of every donor would be published in his paper, no matter how small the gift. Within five months, the World collected more than $100,000 from 120,000 men, women, and children.

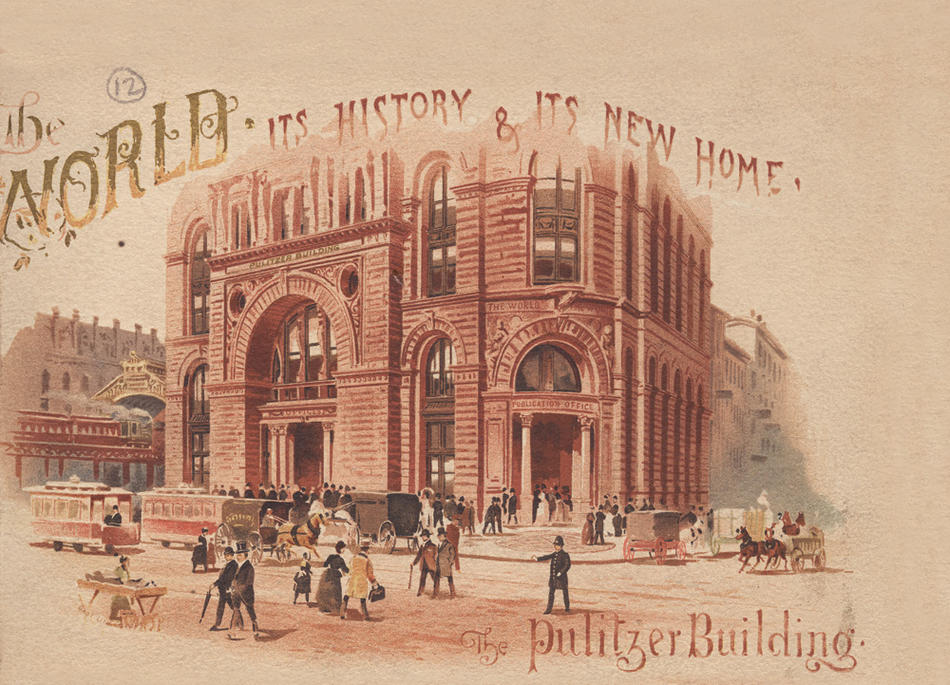

At the time, many of New York’s newspapers, including the World, the New York Times, and the New York Tribune, were located on Park Row, near the Brooklyn Bridge. As they competed for circulation, each paper sought wide-ranging ways to outdo its rivals, whether in the grandeur of its building or in the yellowness of its journalism. Pulitzer commissioned a headquarters for the World that would cast a literal shadow over its competitors. On October 10, 1889, construction began on the New York World Building, at 63 Park Row. It took just fourteen months to build the twenty-story, 309-foot tower — the tallest building in the world.

But Pulitzer’s tower wasn’t finished. In 1905, Pulitzer, mindful of his legacy, hired artist Otto Heinigke to design a large stained-glass window to honor his fundraising crusade for Lady Liberty two decades earlier. Heinigke based the image on the banner’s motif, and in 1908 the window was mounted over the building’s William Street entrance.

Other skyscrapers, meanwhile, had surpassed Pulitzer’s in height, just as other papers would surpass the World’s circulation. In 1931, twenty years after Pulitzer’s death, the World folded, and Pulitzer’s gold-domed monument became just another office building.

The building outlasted the paper, but not by much. On January 7, 1953, the city approved a plan to expand the Manhattan approaches to the Brooklyn Bridge. Pulitzer’s temple was slated for demolition, along with twenty other buildings that stood in the way of progress. By 1954, the World Building was vacant and in disrepair. The furniture, doors, and chandeliers were removed. A collector offered $3,000 for the window, but the city had already bought the building in a condemnation proceeding. It would be up to the city to decide the window’s fate.

At Columbia, John Hohenberg ’27CC, a journalism professor and the president of the journalism school’s alumni association, was determined to rescue the window. Hohenberg, with Herbert Bayard Swope, the former executive editor of the World, negotiated with the administration of Mayor Robert Wagner. A deal was struck. On March 9, 1954, the window was dismantled and carted away to its new home at a cost of $8,000, paid for, in large part, by journalism-school alumni.

On the morning of April 23, 1954, Mayor Wagner, Joseph Pulitzer (grandson of the World’s founder), journalism-school dean Carl W. Ackerman, Columbia president Grayson Kirk, and other dignitaries gathered in Morningside Heights to rededicate the window in a place where it might feel at home: the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. At the ceremony in room 305, Kirk called the window an “enduring memento of the life and work of Joseph Pulitzer and of the friendly and efficient collaboration between Columbia and the city.”

The window stands sentinel in room 305 today — what is known as the World Room. Displayed in a heavy wooden frame inscribed with a dedication to Swope, the colorful glass panel is backlit and aglow at all hours, and serves as a backdrop for many events, including an annual spring ritual in which writers and composers receive one of the world’s most exalted awards: the Pulitzer Prize.