Plunk yourself down in the middle of the work of the artists you’re about to encounter, and you begin to notice certain patterns: a rigorous intellectual component; a shrewd sense of irony and history; a free play of imagination; a confidence built from having exhibited at major local and international galleries, museums, and art fairs; and, most strikingly, an embrace of multiple traditions and media.

“Ask yourself: what is the best way to represent the body of ideas you’re interested in?” says Gregory Amenoff, a painter and the chair of the visual-arts program at the School of the Arts. “People come in as painters, sculptors, video artists, photographers, printmakers, and animators, but they’re put in one large pool, where their peers encourage them to consider what different forms their ideas can take.”

In this virtual gallery tour, curated by artist and critic David Shapiro ’01CC, we see the diversity of forms and ideas that exemplify the Columbia program’s “no walls” interdisciplinary philosophy. There’s Anya Kielar’s Pop-inflected, female-centered collages, assemblages, paintings, and fabric pieces; Marc Handelman’s illusionism and Western mythology, rendered in paintings and installations; Francesca DiMattio’s paintings and Frankensteinian fusions of historical ceramic idioms, inspired by Chinese porcelain and the French rococo; the digitally induced paintings and search-term mashups of Kevin Zucker’s technology-meets-culture ruminations; Laleh Khorramian’s fantastical, culturally influenced paintings, drawings, installations, and digital animations; and the ecological concerns and political critiques of the Amazon-sojourning sculptor David Brooks.

Here, the medium isn’t the message, but rather, it’s the channel through which the message is most effectively realized; here, form leaps to the service of ideas. This scheme would seem to reflect a comment by Amenoff on Columbia’s program:

“Just because you come in as a painter”, he says, “doesn’t mean you can’t branch out.”

David Brooks

Visiting David Brooks’s live-work loft studio in the Dumbo neighborhood of Brooklyn is like taking a trip to a natural-history museum. Mantels are lined with skulls, teeth, petrified wood, and taxidermied creatures: a bobcat, a fish, a flock of migratory birds. It’s a fitting environment for Brooks ’09SOA, who creates sculptures — often monumental in scale — that investigate the natural world and its relation to an encroaching human culture.

New York audiences are most likely to know Brooks from his site-specific installation Preserved Forest in MoMA PS1’s 2010 exhibition Greater New York. In this piece about deforestation, Brooks arranged nursery-grown trees in a sunken atrium to represent an Amazon rainforest. He then sprayed the forest with a cement truck’s worth of latex-laced concrete, a material that is susceptible to fissure from plant growth. Over time, the trees sent shoots through and around the concrete, fulfilling his prediction that the concrete and the organic matter would “begin to define each other.”

In another recent piece, Still Life with Stampede and Guano (2011), Brooks allowed concrete lawn sculptures of charging lions, elephants, and horses to collect a patina of guano from deliberate exposure to seabirds at the Florida Keys Wild Bird Center.

Anya Kielar

The art of Anya Kielar ’05SOA typically explores generalized images of women, making frequent reference to the histories of both painting and photography. In WOMEN, a 2012 solo show at Rachel Uffner Gallery on the Lower East Side, Kielar used nontraditional “painting” methods, including textile dye and devoré — a burnout technique typically used for T-shirts. These works, inspired by set design, folk art, early-twentieth-century painting, and the notion of “primitivism,” were suspended between ceiling and floor throughout the gallery. In an earlier group of large-scale works she calls “sprayograms,” Kielar employed a stenciling technique to create vibrant images on paper that hover between the abstract and the figurative. While the sprayograms make use of acrylic paint, they allude to a type of camera-less photograph called a “photogram,” which was championed by the surrealist Man Ray, who called his “rayographs.”

Francesca DiMattio

Francesca DiMattio ’05SOA titled one of her recent ceramic works Jardinier (Gardener), a label that captures not just the piece, but something larger about her work as well. After years of working only in Brooklyn, DiMattio became newly inspired by the bucolic spaces of rural upstate New York, where she spent much of her childhood. Deciding to return to familiar territory, she set up shop on the west bank of the Hudson in the ceramics studio that her mother built for crafting terra-cotta pieces for the family’s extensive gardens.

DiMattio makes her painted ceramic pieces by casting porcelain, then fusing and intentionally rupturing the forms before firing. A painter by training, she particularly relishes the process of surface decoration. While developing her ceramics practice, DiMattio has continued her earlier work of creating large-scale paintings of inventive architectural spaces. Like her clay works, these paintings combine patterns, representations of textures, and stylistic allusions.

Kevin Zucker

In the mid-nineties, when most of us were sending our first e-mails, Kevin Zucker ’02SOA, then an undergraduate at the Rhode Island School of Design, was finding a way to incorporate digital drawing into his painted canvases: “I thought the lousiness of that fit might make for something interesting,” he says. At Columbia, he practiced what would become his signature technique: creating and printing digital drawings, then transferring the ink from the prints onto acrylic-primed canvases. He continues to work in this vein in his Brooklyn studio, adapting with evolving technology.

Much of Zucker’s recent work makes use of the three-dimensional modeling program SketchUp. For one series, which was on view last year in a solo show at the Lower East Side gallery Eleven Rivington, Zucker generated digital representations of imagined vacation resorts in the rain. For another recent painting, Zucker based his forms on a mashup of Internet search results for the keywords “abstract sculpture,” and in Amalgamated Sculpture (2010), he created three-dimensional forms from a similar search.

Laleh Khorramian

"People want to see my work as Iranian,” says Laleh Khorramian ’04SOA, “but why don’t they ask what’s Floridian about it?” Khorramian was born in Tehran and raised in Orlando, a place she describes as quintessentially American, and her artwork — paintings, drawings, digital animations, and installations — fluidly draws images and ideas from both places and beyond. Her current fascination is science fiction.

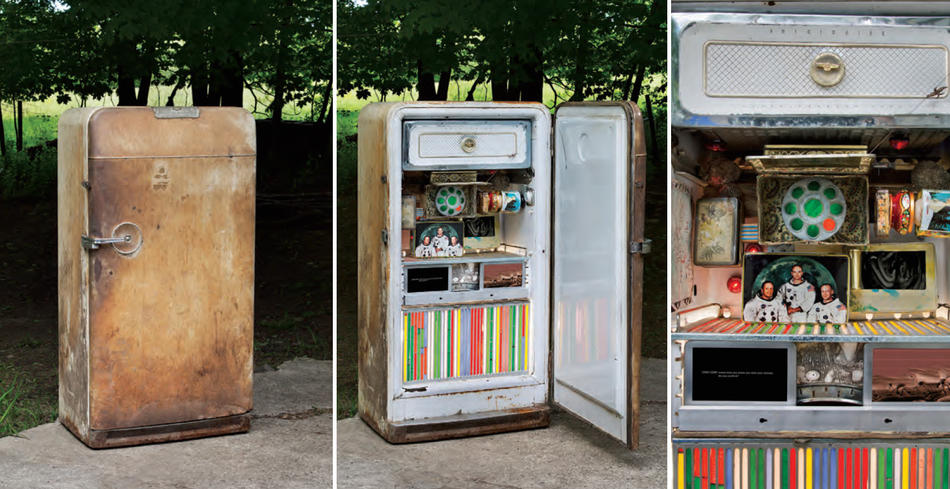

Khorramian creates darkly surreal monotype prints, which she makes by painting in oil or ink on glass, then transferring the image to paper. She also uses these images as cells in digital animations, and has begun to take her mixed-media approach a step further, incorporating these animations into objects within larger installations. For example, she fit a screen playing an animation into a refrigerator as part of her 2013 solo project for Art Basel. The project follows a sci-fi narrative of a lieutenant in the future banished to a planet ravaged by chemical waste.

Marc Handelman

When the curtain is pulled back in The Wizard of Oz, the audience discovers that “there is something more real in the illusion of something than the real thing.” Marc Handelman ’03SOA invokes this critique by Slavoj Žižek while talking about illusionism in his paintings, large-scale oils that move deftly between abstraction and representation, focusing on landscapes, surfaces, and qualities of light.

Handelman’s new, yet-to-be-exhibited paintings fill every wall of his studio in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood. The works are based upon manipulated stock images of patterns in rock surfaces. In this series, Handelman sprinkles crushed-glass particles onto the wet paintings, giving them a velvety quality and shifting tones that impart a resemblance to computer screens.

Handelman based an earlier series on weapons manufacturers’ advertisements, focusing on the clichéd image of the sunset over the endless American landscape. He used various painting processes to represent and disrupt these commercial visions of the sublime. In one such technique, Handelman painted an image on a preliminary surface, then transferred it to the canvas using a sheet of plastic, resulting in an image interrupted with random fragments.