“Most academics were critics of the Iraq War. There’s no question about that. Most saw it as a needless war, a war brought about by blundering politicians, a war clothed in the language of freedom but completely crass and reprehensible in every way. And now there’s a whole spate of books that view the Civil War through this lens.”

Eric Foner ’63CC, ’69GSAS looks up, his soft eyes peering over the top of his tinted glasses at the nearly 250 undergraduates crammed into an auditorium of the International Affairs Building on a rainy Wednesday afternoon. The seventy-one-year-old Columbia professor, widely regarded as the most important Civil War historian of his generation, is nearing the end of one of his favorite lectures for the final time. A dozen or so graduate students, alumni, and local retirees are standing at the back of the auditorium; many chose to audit the course upon learning that Foner will soon retire.

“What do we make of this?” he asks.

For the past hour, Foner, speaking in a folksy tone with a hint of a Long Island accent, has been discussing how historical interpretations of the Civil War have evolved over the past 150 years. He has focused specifically on moments when historians have challenged the idea that the Civil War was morally justified and necessary because it led to the emancipation of four million slaves. These challenges were particularly pronounced in the 1930s and ’40s, he says, when many historians, shocked by the apparent pointlessness of World War I, projected their disgust back onto the Civil War, seeing not a principled fight over slavery but merely a clash between industrial and agrarian economic interests.

“World War I discredited the idea of linking war with high, noble rhetoric,” says Foner. “Historians came to feel that explaining war in large abstract terms tended to dignify it.” Similarly, the work of many young Civil War historians today gives the impression that greed, hatred, and vengeance were the main drivers of the conflict, and that if only cooler heads had prevailed, politicians might have resolved their differences at the negotiation table. This strikes Foner as naive. Few seasoned scholars, he says, believe that Southerners would have given up their slaves anytime soon without a fight.

“I think if you’re going to say the war was unnecessary, you have to have an alternative scenario that would have led to abolition,” he says. “And I have never seen it. I have never once seen a plausible scenario for the peaceable end of slavery.”

He looks down at his notes, and paraphrases W. E. B. Du Bois: “War is murder, force, and anarchy. Yet sometimes it produces good.”

Another pause. “Somehow we have to find a historical stance that can take into account all these things.”

The moment is quintessential Foner. Reading history, his lecture would suggest, requires us to look at the past from all angles, yet to not lose sight of clear moral truths. To test our assumptions without sliding into relativism or intellectual gamesmanship.

It’s a moment soon to be relived thousands of times over, on computer screens around the world.

Call in the Cavalry

“Like any theatrical production, a lecture is not forever. You perform, and it’s gone. At some point I realized that I wanted to preserve a little bit of this.”

That’s how Foner describes his decision to turn his Civil War lectures into an online course that is now available to anyone with an Internet connection, for free, on the distance-learning site edX. After thirty years at Columbia, Foner decided a couple of years ago that he would wind down his teaching and retire in 2016. And as he prepared to teach his signature course for the final time last spring, he realized that he wasn’t ready to consign his lectures to history.

“Teaching is actually what I spend more time on than writing,” says Foner, the author or editor of twenty-four books, including The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, which won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for history. “When you do it well, I think you can reach people in a very direct and powerful way.”

In the summer of 2013, Foner approached a team of Columbia multimedia specialists about the prospect of documenting his lectures. His request was simple: record them and post them online for anyone to watch. The specialists, based at the Columbia Center for New Media Teaching and Learning (CCNMTL), had a more ambitious idea. They had recently begun working with a handful of Columbia professors to create the University’s first massive open online courses, or MOOCs, which are free Web-based courses that enroll enormous numbers of people, sometimes tens of thousands or more. MOOCs had become popular rather suddenly the year before and represented a radical experiment in higher education. Whereas online courses offered by colleges and universities previously had enrolled no more than a few hundred students at a time, thus allowing students to have personal contact with their instructors, albeit over e-mail or video-conference, MOOCs were too big for that: students in a MOOC could expect to communicate with an instructor only in chatrooms open to thousands of people and to be evaluated by computerized multiple-choice tests. Few colleges give academic credit for taking MOOCs. The upside is that huge numbers of students get access to a top-notch professor, typically from an elite university, who leads them on a semester-long intellectual journey that in many ways mirrors the experience of taking a traditional college course.

“If you can’t afford college, or if you’re simply curious what it’s like to enter an Ivy League classroom, now you can do it,” says Maurice Matiz, the director of CCNMTL. “There is a profound democratizing effect here.”

To Foner, the prospect of getting involved in a high-tech teaching experiment in the twilight of his career held no small amount of irony. Although a dynamic teacher — engaging, sharp-tongued, and at times wickedly funny — he’s not technologically savvy. His idea of a multimedia presentation is taking a newspaper article out of his jacket pocket, uncrumpling it, and reading it aloud.

“It’s almost absurd that I’d be doing this,” says Foner. “I’m not on Facebook or Twitter. I still write with piles of paper around me. I’m one of the few professors at Columbia who doesn’t let students use laptops in class. I think they’re distracting. They can take notes by hand like it’s always been done.”

And yet a MOOC, Foner realized, suited his situation perfectly. Because it would be largely automated, he could oversee its operation in just a couple of hours a week until he retired; thereafter, someone else could take over the responsibility of moderating the course’s discussion-board and chatroom conversations, enabling his virtual self to teach on forever.

“This could eventually reach far more people than have ever read my books,” he says. “How could you say no to that?”

Let’s Roll

Following a couple of brainstorming sessions last fall, Foner and his new CCNMTL colleagues agreed on the basic form his MOOC would take: it would rely on video footage of Foner’s actual lectures (some MOOCs are made in a recording studio, with a professor speaking directly into a camera), edited into roughly ten-minute segments, with supplemental video clips, multimedia features, and quizzes dispersed among them. While any member of the public could access the content at any time, people who enroll in the course would be encouraged to watch the lectures and do the assigned readings at a designated pace — over a ten-week period — so they could discuss what they were learning together.

“We can’t possibly grade thousands of papers, right? OK, so that’s a drawback — the lack of writing. But in other ways, we want to give people an experience that is as grueling as they want it to be,” says Tim Shenk ’07CC, a history PhD candidate who is Foner’s head teaching assistant and who would work closely with the CCNMTL team in developing the course’s online version. “One key to that is creating a sense of community online so that people feel that they are part of a collective experience, and so that they can challenge, question, provoke, and support one another.”

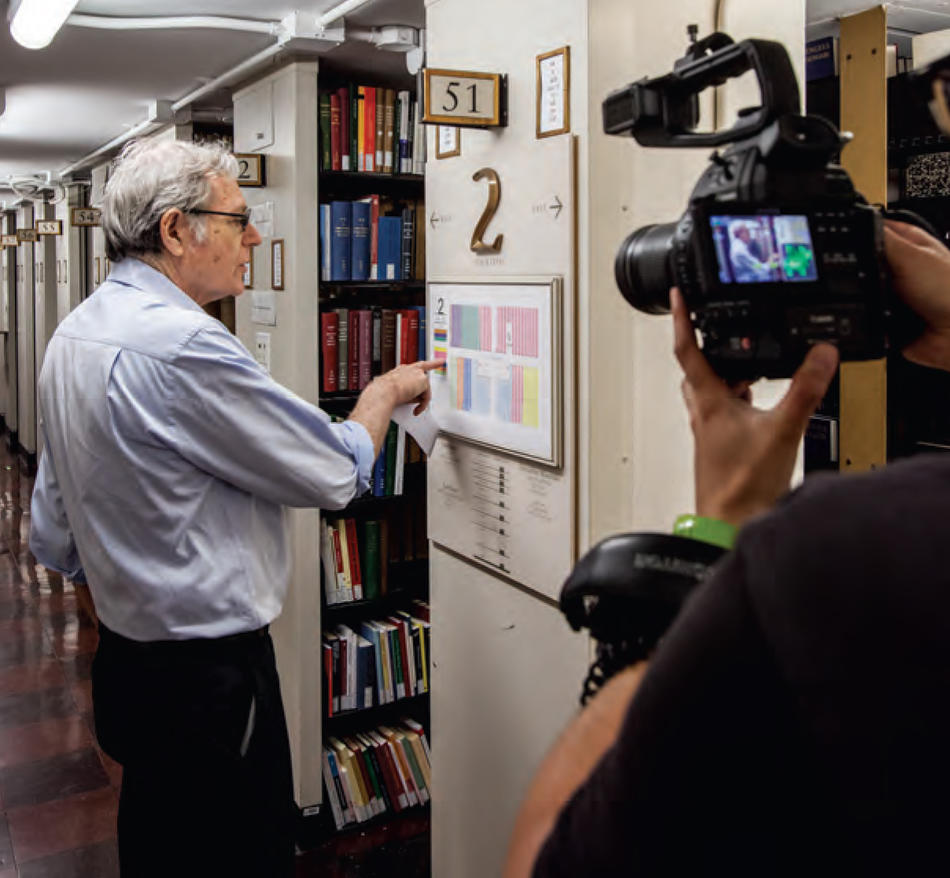

This past January, a team of producers from CCNMTL got started on the hard work. They lugged cameras, tripods, lights, and microphones to Foner’s class every Monday and Wednesday afternoon, recording his lectures in high-definition video. They filmed weekly discussion sessions in which small groups of students debated the week’s readings with Foner and his teaching assistants around a conference table. And they shadowed the professor on trips to local archives, filming him as he examined Civil War–era artifacts.

“The closest thing I’d ever done to this was help curate a museum exhibition,” says Foner. “As a historian, I’m not used to working collaboratively. When I’m writing books or preparing lectures, I organize the information any damn way I want. It was interesting to learn a new medium.”

Still, Foner approached the work with some trepidation. He had questions about the way his MOOC could be used, questions that echoed a larger debate playing out across the world of higher education. Many educators foresaw a time when colleges and universities would issue credits to students for taking MOOCs, even those produced at other institutions. Some of the more messianic proponents of distance learning thought this would bring much needed efficiency to higher education, allowing colleges to trim their teaching budgets and thus rein in spiraling tuition costs, all while giving a broader swath of students access to the very best teachers. Skeptics feared these online courses would provide a watered-down education, with students at cash-strapped public institutions denied the face-to-face time they needed with human instructors, whose numbers would be decimated. Foner, like many professors creating MOOCs, recoiled at the idea that his effort could put fellow academics out of work.

“I’m old-fashioned enough to think that the only way to get a serious education is to be in a room with other human beings,” says Foner, who has been honored for his skills in the classroom many times, including in 2006, when he received Columbia’s Presidential Award for Outstanding Teaching. “I can’t imagine the future of higher education is watching a computer screen. That can’t possibly replace a real professor. At least I hope not.”

Straight to the People

The Civil War course that Foner teaches has long been a favorite of Columbia students. Foner’s mentor, James Shenton ’54GSAS, taught it before he did. One of Columbia’s most beloved teachers, Shenton became more widely known in the 1960s when he presented “The Rise of the American Nation,” a seventy-six-hour lecture series, in installments on public television. Shenton’s star turn didn’t raise many eyebrows among his colleagues, Foner says, because Columbia historians have traditionally encouraged one another to share their scholarship with the general public.

“At some institutions, you’d be looked down upon for speaking directly to the masses,” says Foner, who is the DeWitt Clinton Professor of History, a position that was held before him by Richard Hofstadter ’42GSAS, another great public intellectual. “It’s the opposite here — making your scholarship accessible to people is seen as part of your job.”

That Foner enjoys this part of his job, and that he is uniquely gifted at it, is evident every time he stands in front of an audience. He does so frequently, not just in the classroom but also before small-town historical societies, public-school assemblies, alumni groups, and gatherings at Civil War battlefields and memorials across the country.

Speaking in simple and colorful language that is entirely free of “academic gobbledygook,” as he calls it, Foner will effortlessly weave together strands of scholarship about nineteenth-century US politics, economics, demographics, racial dynamics, and international relations to help people make sense of the most complex issues of the era: How did Americans understand the concept of freedom back then? How did they apply the concept to black people, women, and members of various immigrant groups? Were Southerners and Northerners really that different in this regard? How did their regional economies influence their views? And how might the course of history been altered had the US government allowed the Southern states to secede?

“One of the things Professor Foner is always doing is relating history to the present day,” says Anna Martelle Miroff, a College senior who took the course last spring. “He shows you that history is alive, and that its interpretation is an ongoing project that can reveal as much about the historians producing the scholarship as the subjects they’re writing about.”

The owners of edX, a nonprofit MOOC platform that Harvard and MIT operate jointly, saw the potential immediately. Soon after receiving a call from Columbia officials last fall about hosting Foner’s course, a deal was being negotiated.

Guaranteed Giveaway

By the time Foner and Columbia joined forces with edX last winter, the University had already produced eight MOOCs on topics as various as virology, economics, finance and banking, natural language processing, and electrical and computer engineering. All were hosted by Coursera, a for-profit company that had been launched by two Stanford professors in early 2012. Coursera quickly became the world’s largest MOOC provider, hosting hundreds of courses created by academics from dozens of institutions. The company’s visibility gave a handful of Columbia faculty access to more students than they’d ever had in their careers; in 2013 alone, over four hundred thousand people enrolled in Columbia courses on Coursera.

“You can get information out to so, so many people,” says Columbia microbiologist Vincent Racaniello, whose MOOC on virology last year drew an audience of more than forty thousand people. “In my case, I’m teaching people all over the world about vaccinations, infectious diseases, outbreaks like Ebola. I think virology is a subject that everybody should know about. And a lot of people don’t have access to good science instruction where they live.”

Foner opted against working with Coursera in favor of edX, which was a few months younger than its chief competitor and considerably smaller. He thought edX, being a nonprofit consortium, would be less likely to take steps that might jeopardize faculty jobs at brick-and-mortar institutions. Neither company had yet figured out how to sustain itself financially. They were experimenting with the same basic strategies: selling certificates to students who successfully completed courses and licensing colleges the ability to issue credits to those who earned them. But edX was positioning itself as the more service-minded of the two, offering fewer but more academically rigorous courses and conducting serious research on its users’ experiences, analyzing how people take in and retain information, depending on how it is presented.

“I don’t want to be involved in making anybody rich,” says Foner, who received assurances from edX executives that no college or university would be permitted to issue credits for taking his course. “If another teacher wants to use it as a supplement to their lesson plans, that’s fine. Anyone can do that by visiting the site. But nobody’s going to commercialize this in any way.”

That’s not to say that Foner or anybody else can perfectly predict the ripple effects of his MOOC. Might working adults enroll in his MOOC instead of, say, taking a history course at a community college?

“I suppose so; this is a disruptive technology, right?” he says. “But it’s hard to imagine how many people that will apply to. And maybe someone who takes this course will become so interested in history that they’ll subsequently enroll in college.”

Fables of the Reconstruction

In talking to Foner, it is clear that he wrestled with the decision to create a MOOC. But it is also clear that he, like any passionate teacher, believes that people really need to know what he knows about his subject. The Civil War, Foner has often said, is the most important episode in American history, the cauldron out of which our modern nation, with its strong federal government, modern economy, and seemingly intractable cultural divide between North and South, was born. The era still fascinates us, he says, in part because we haven’t yet worked through a lot of resentments formed during the war and during the turbulent Reconstruction period that followed. Americans have a hard time seeing eye to eye on many social and political issues, he says, because of misconceptions that persist about the era.

What misconceptions?

“Like that slavery wasn’t the real cause of the war,” he says. “That the real issue was states’ rights or disagreements over trade from fully confronting this ugly part of our nation’s history.”

But the single biggest misconception about the era, and the one whose influence on public life today is most pernicious, Foner says, is the notion that white Southerners were mistreated in the decades following the war. US historians up until the mid-twentieth century, he says, perpetuated the idea that the North had exploited the postwar South economically, had granted former slaves in the South too many civic rights too quickly, and had generally micromanaged the region’s affairs in a way that gave white Southerners reason to feel embittered for generations to come. This view, Foner says, has since come to be seen as inaccurate and deeply racist — the result of white historians’ attempts to intellectually legitimize Jim Crow. Yet the notion persists that Dixie was victimized.

“I think there is a wider gap between historians’ understanding and popular understandings today vis-à-vis Reconstruction than any other period in American history,” Foner says. “One of the footholds of modern conservatism is this whole idea that white Americans have a right to feel aggrieved about their lot. We saw that in the white backlash against the civil-rights gains of the 1960s, and we still see it in some arguments against affirmative action. It dates back to that old historical work. I feel an obligation to correct some of that bad old history, and to get good, up-to-date history out to as many people as will listen.”

Spirit of Compromise

A summer storm threatens as Foner takes a seat in a windowless conference room on the fifth floor of Butler Hall. It is a few weeks before his digital course will go live on edX, and “the MOOCers,” as he affectionately calls his CCNMTL colleagues, are discussing the details of its format.

Stephanie Ogden, a digital-media specialist, is demonstrating how students will be able to navigate within Foner’s lecture videos by scrolling through an accompanying transcript.

“I can jump down to here,” she says, clicking on a word next to the screen, “and the video will follow.”

“Oh, that’s pretty cool,” Foner says.

“We can speed it up as well,” she says, setting the video to run at 1.5x speed, giving Foner’s voice a slightly high-pitched tone.

“That’s very popular in the MOOC world. People like to go a little faster,” says Michael Cennamo, an educational technologist.

“People tell me I speak too fast to begin with,” cracks Foner, a native New Yorker. “When I taught in the South, they begged me to speak slower.”

A recurring point of debate between Foner and the MOOCers has been how frequently his lectures ought to break for poll questions, quizzes, and other interactive features. Such features are thought to help online students feel engaged; Foner worries that they will simply be distracting. In fact, Foner had initially suggested that his lectures run as uninterrupted seventy-five-minute video clips.

“I was quickly informed that’s not how things work,” he says. “Apparently people’s attention span online is rather short. Nobody wants to sit there for an hour and fifteen minutes.”

The current plan, Cennamo explains, is to embed two pop-up questions within each ten-minute lecture video.

“To see if you’re paying attention,” chimes in Tim Shenk, the history PhD student working on the project.

“Right,” says Cennamo, who adds that edX can later analyze students’ responses to these multiple-choice questions for insights about how they are learning.

“Wait a minute. Two per clip? Fourteen per lecture? That seems like a heck of a lot,” Foner says. “It would be as if in the middle of a book chapter you’re suddenly throwing questions at the reader. It interrupts the narrative. So two seems like a lot.”

No problem, says Cennamo. One question will do.

“I’m impressed with this group,” Foner says later. “So I’ve been happy to go along with what they think will work — within reason.”

Civil Discourse

The first part of Foner’s three-part edX course went live on September 17. Entitled “A House Divided: The Road to Civil War, 1850–1861,” it is running for ten weeks; it will be followed by “A New Birth of Freedom: The Civil War, 1861–1865,” which will launch on December 1, and “The Unfinished Revolution: Reconstruction and After, 1865–1890,” on February 25, 2015.

More than six thousand people from 136 countries enrolled in “A House Divided” as of its launch date. Three-quarters of them live in North America; many others are from Europe, Asia, and South and Central America. Only 17 percent described themselves as students in an introductory poll. Nearly a third identified as high school teachers, college instructors, or professional historians. The vast majority described themselves simply as “history enthusiasts.”

“It looks like a lot of people taking the course are doing so for self-enrichment, which makes sense, given the subject matter,” says Shenk. “Learning about the Civil War might make you a better citizen, but it probably won’t get you a new job.”

Judging by online discussion taking place on the course’s site the first week, those who signed up share a love of learning — and little else. Among them is a ninety-year-old Texan who’s earned several degrees in retirement; a thirteen-year-old British homeschooler; a woman from Nigeria who is a US-history buff; a New York City high-school teacher who is taking the course with several of his students; someone from Switzerland looking for answers to specific questions (“Frustrated I don’t understand why Northerners cared so much about slavery when they certainly didn’t consider African Americans to be their equals”); and an eighty-four-year-old man from Toronto who warns his peers how slowly he’ll be typing (“Only using my right index finger ... I can’t get enough education!”).

“The diversity of experiences people are bringing to this is pretty amazing,” says Shenk. “It’s obviously gratifying to open up the Columbia experience to people who might never step foot on this campus.”

The challenge now faced by Shenk and seven other history PhD students working on the course is formidable: to corral the online conversations taking place among thousands of people whose backgrounds and educations vary wildly, into the type of provocative yet respectful dialogue that is the hallmark of any great classroom. Each Columbia graduate student is spending several hours a week reading online posts, chiming in to answer questions, guide conversations, and tamp down any misguided comments. Each week, they earmark ten particularly insightful student posts for Foner to respond to personally. They are also encouraging students to form breakout discussion groups with people who share their interests or educational backgrounds, which they can do through the course’s Facebook and Twitter pages.

“The best way for smaller communities to form, based on the lessons of previous MOOCs, is to let it happen organically,” says Shenk. “Our strategy here is to gently push people in the direction we’d like to see them go.”

Foner, meanwhile, is watching the project unfold with an excitement tempered only slightly by its endless unknowns. He has begun to wonder: How long will the course remain relevant? Will there come a time soon when he’ll want to update its content? Or might it be wiser to retire the course altogether in a few years, thus clearing the way for some younger Civil War historian to assume the throne?

For now, though, he’s trying not to over-analyze. “I’m skeptical of a lot of things,” he says. “But I’m not skeptical of this.”

Lectures on Your Laptop

Three years ago, nobody outside a small circle of distance-learning experts had ever heard of MOOCs.

Since then, these “massive open online courses” have shaken up the world of higher education, removing barriers to access and provoking intense debate about the promise and limitations of distance learning.

An estimated fifteen million people globally have enrolled in one of these free video-based Internet courses, which are, as their name suggests, massive in size and open to anybody, regardless of his or her academic background. Most MOOCs are produced by elite universities as a way to showcase their best teachers and are hosted by outside Web companies that agree to share any revenue they generate — such as by selling certificates to students who complete them. But few MOOCs have generated enough money for universities to even recoup the cost of making them, in part because they have low completion rates and because the value of the certificates is unclear.

“The main reason you create MOOCs is to enable faculty to share knowledge with people who might have no other way of accessing it,” says David Madigan, the University’s executive vice president and dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “That’s front and center. It’s part of our service mission. But there are side benefits. We’ve found that some people who take our MOOCs end up enrolling in Columbia degree programs, for instance. There’s also the fact that whenever you experiment with new methods of teaching, you stimulate creative thinking and introspection among the faculty about how they might improve the learning experiences of all of our students — whether on campus or online.”

About a dozen Columbia professors have made MOOCs so far. In addition to historian Eric Foner, they include economist Jeffrey Sachs, physicist Brian Greene, virologist Vincent Racaniello, and computer scientist Michael Collins. Most of these MOOCs have been produced in-house by the University at a cost of anywhere from $10,000 to $150,000 apiece. (A few MOOCs starring Greene have been produced and paid for by his own World Science Festival.) The courses have provided free instruction to some 650,000 people around the world, with less than 5 percent of them finishing a course — a completion rate that may sound deflating but is in line with industry trends.

“Naturally, since MOOCs are free, a lot of people will try out a course and then opt out if they decide it’s not for them,” says Maurice Matiz, the director of the Columbia Center for New Media Teaching and Learning, which produces the University’s MOOCs.

According to Madigan, the University is likely to continue producing a “moderate number” of MOOCs each semester for the foreseeable future. This is among the recommendations soon to be issued by a faculty task force on online education that Columbia convened last year and that Madigan chairs; the task force is now preparing a full report to be released this fall.

“Some universities are producing tons of these courses, and others none at all,” he says. “Columbia is treading a middle ground. We want to be selective, developing MOOCs for faculty who are at the very top of their fields and also exceptional teachers. That’s the sweet spot, when you’re offering the world something that’s totally unique.”

Learn more about Columbia’s MOOCs and other online programs at online.columbia.edu.

Andrea Stone ’81JRN contributed reporting.