When discussing Robert Moses ’14GSAS, ’52HON, it is amazing how many times historians and journalists use the word ram as a verb. Sometimes it’s figurative, sometimes it’s literal. “Moses rammed through the Board of Estimate most of his original plan for Washington Square Southeast, including the high rises and arterial roadway,” writes Joel Schwartz in The New York Approach: Robert Moses, Urban Liberals, and Redevelopment of the Inner City.

“After the war,” says biographer Robert A. Caro, “Robert Moses rammed six huge expressways across the heart of New York.” Caro ’67JRN is the author of the colossal (and colossally popular) The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, the 1974 book that defined Robert Moses for most of us. If ever there was a story of a human battering ram — and of those who got in the way — then Caro’s book is it.

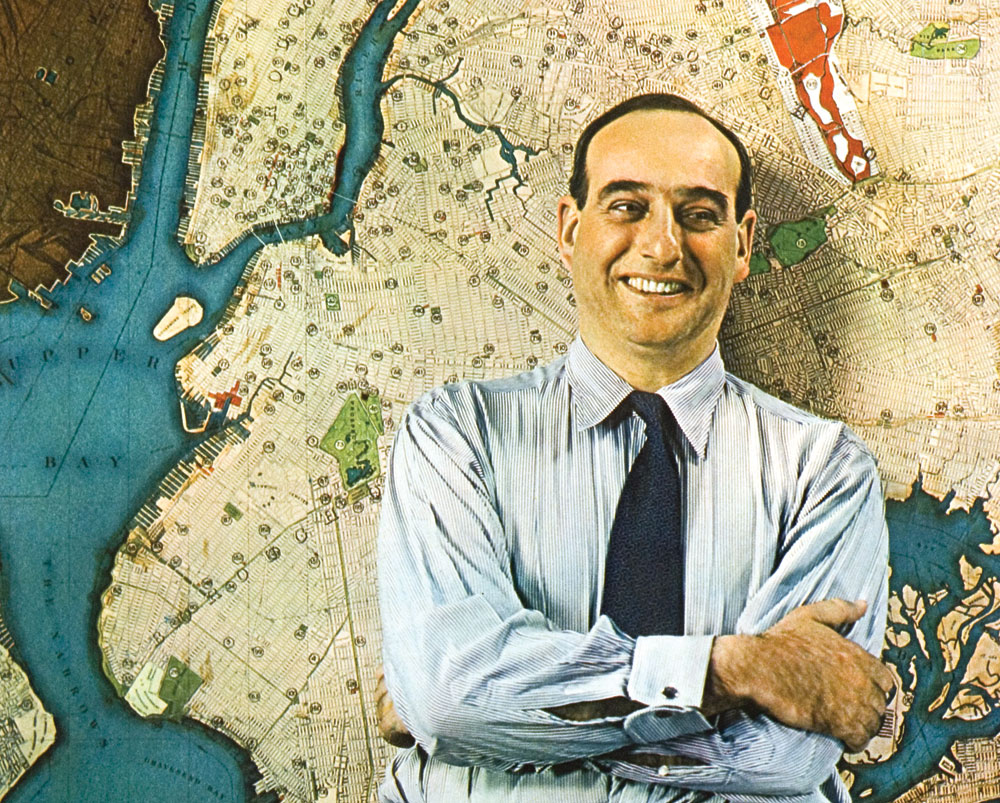

“Robert Moses believed his works would make his name immortal,” says Caro, “and looking at New York today, it would be hard to argue that he was wrong. The city, and indeed the whole region in which we live our lives, is still one shaped by his vision and by the savage determination with which he drove it to realization. He was for 44 years the shaper of New York, and today, decades after he left power, his influence in New York simply dwarfs that of any other public official or any private developer.”

That influence on the city — the roads and parks and buildings Moses left behind — is the primary focus of a series of exhibitions and symposia opening around the city this season under the rubric Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York (see page 36). More than 25 years after Moses’s death, we’ll have the opportunity to reassess his creations and proposals through the lens of early-21st-century New York, a city and time that share little with the tottering New York of the mid-’70s, when The Power Broker was published and the Daily News relayed President Ford’s sentiments to the city: DROP DEAD.

Cutting Through the Politics

“There’s a pent-up frustration that big public building and infrastructure projects can’t seem to get built in New York any more,” says the exhibitions’ curator Hilary Ballon, architectural historian and professor in Columbia’s department of art history and archaeology. “The failure of anything to happen at Ground Zero, in particular, triggered a sense that a strong leader who could cut through the politics and the parochialism might make a difference. Moses is a metaphor for action in the face of big problems.”

Moses tackled big problems from the very start. His reign began in 1924, when Governor Al Smith named Moses to head the New York State parks council. In his first decade on the job, Moses built close to 10,000 acres of parks and the first of the automobile parkways that run across Long Island. Immediately after becoming Mayor La Guardia’s parks commissioner in 1934 (and while still holding the state job), Moses threw himself into hundreds of projects large and small that in short order would lead to the rehabilitation of the Central Park Zoo, the construction and renovation of hundreds of parks and playgrounds, the building of a dozen beautiful swimming pools in working-class sections of the city, and the completion of the West Side Highway and the Henry Hudson Bridge. Before World War II, through force of will and the brilliant exploitation of Depression-era federal funding, Moses reshaped the contours of New York City through such public-works schemes as the Triborough Bridge complex and the Grand Central and Interborough Parkways. But it was the postwar explosion of federal money for slum clearance and public housing and, in the ’50s, for interstate highways, that made his control over public works nearly absolute.

After the war, adds Caro, Moses also began to build in populated areas. Whether for high-rise housing projects or highways, Moses’s indifference to the neighborhoods his projects bulldozed and to the hundreds of thousands of people he displaced was chilling. As he once said during a television interview, “People must be inconvenienced who are in the way.”

But people got sick of being “inconvenienced,” a cynical euphemism indeed for being evicted and having their communities dynamited off the map — as happened to the 5000 Bronx residents who lived where Moses wanted the Cross Bronx Expressway to go. (He dismissed alternative routes out of hand). “Cities are created by and for traffic,” he wrote. No wonder many felt that Moses and other planners who branded this or that block “blighted” simply didn’t like cities. That was the view of Jane Jacobs, whose 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, takes aim against what urban renewal had come to mean. Jacobs and other neighborhood-oriented urbanists saw that the neighborhood — the street and sidewalk — were what made the city, not the speed of the traffic cutting through it. Although Moses was still an awesome force, society’s way of thinking about cities was changing. Neighborhoods, for so long seen by Moses as impediments to traffic and progress, were coming to be understood as the fabric that kept cities together.

Built to Last

“In some ways, we’ve been coasting for half a century on what Moses already built,” says Kenneth Jackson, Barzun Professor of History and the Social Sciences. “He was swimming with the tide of history. Without those bridges and tunnels, without those expressways, without the public housing, without the recreational facilities, the quality of life in the region would be much lower than it is now. Horror though it may well be, how do you travel between Boston and Pittsburgh if you don’t go on the Cross Bronx Expressway? You’ve got to move laterally at some point. I agree with all the points that Jane Jacobs made about neighborhoods and not being slaves to the automobiles. But at the end of the day we have to have roads. We can’t just damn the automobile and the truck.

“What Robert Moses did, he did well and efficiently and quickly, and do we ever need that today in the public sector, which has become synonymous with slowness, overruns, inefficiency, and wrongheadedness,” says Jackson. “That isn’t what Moses represented. He said, ‘Let’s get it done.’ It doesn’t save the public money to sit around and hassle about it forever.”

Hilary Ballon, too, suggests that we need to look at our cities regionally as well as locally. “Jacobs and Moses represented opposing positions,” she says, “which ideally should be brought together. As urbanists, we should attend to the quality of our streetscapes; but not all the problems of the city are neighborhood-scale problems. Transportation infrastructure or big buildings may have some negative impacts on a particular neighborhood, but may be desirable for the city as a whole. I think the interest in Moses now is about a desire for a kind of correcting force.”

Both Jackson and Ballon readily acknowledge the inhuman side of Moses so dramatically portrayed by Caro’s book. “Moses had an arrogant, brutal, pushy, obnoxious quality, and he used that quality strategically to bully his enemies and to intimidate potential enemies so that they didn’t dare object,” says Ballon.

“As a society and a region,” says Jackson, “we’re going to have to figure out a way to put together big projects again. I think the Bloomberg administration understands that if New York wants to remain the greatest city in the world, then you can’t freeze it in the past. It has to grow with the times, and Robert Moses helped it grow with the times. We need someone or some way of dealing with the twenty-first century in the way he dealt with the twentieth.”