“What will not be forgiven me by the reader of these diaries is my obstinate unhappiness,” Alfred Kazin wrote in 1968. “Lord, what a disease, what sentimentality, what rhetoric! What an excuse for not living.”

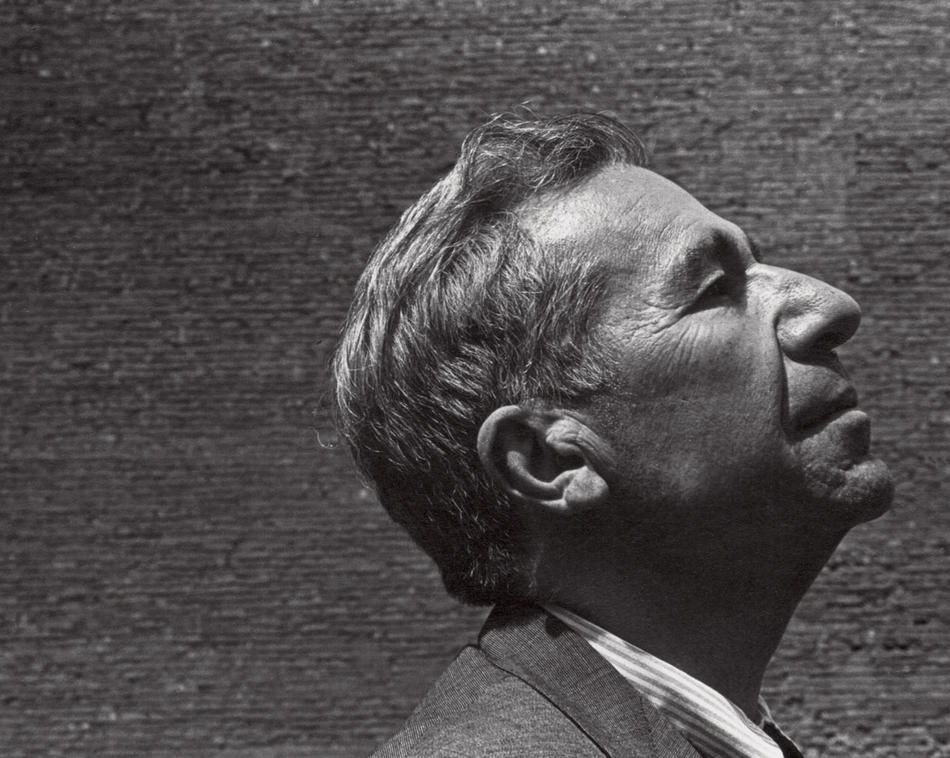

What a lack of self-awareness, the reader is tempted to add. Kazin ’38GSAS, a public intellectual who helped shape the American conversation on literature and politics for nearly 60 years, had one of the 20th century’s most alert, curious, passionate minds, and Alfred Kazin’s Journals is a 600-page monument to its indomitability. Kazin suffered from chronic dissatisfaction, to be sure, but that seems to have been the necessary condition of his restless, searching intellect. (It’s also the human condition.) And for every despairing passage in the book there’s another that reaffirms his love of literature and of living. After reading Emily Dickinson in 1960: “Every day my cup runs over. I have so many perceptions. They bombard me. . . . One has only to get up in the morning to face in the direction of hope.” These are not the words of an obstinately unhappy man.

In fact, the reader of these diaries will find any number of things harder to forgive Kazin, including his willingness to forgive himself (for his almost pathological skirt-chasing, among other behaviors), his odd self-deceptions and social myopias, and his assumption that these diaries would one day have readers. He was right about this last point, obviously, but now those readers can never be sure of the extent to which he was performing, and thereby denying them the thing they most want from private notebooks: the private self.

That said, there’s not much evidence of self-presentation here. If Kazin was writing with posterity in the back of his mind, it was in the very back. As a matter of principle, his ultimate loyalty was to “the subversive, the indefeasible truth of the human heart,” and he distrusted writing that seemed overdetermined or excessively conscious of its audience:

Everything that is really good — in [Edmund] Wilson, in [André] Malraux — has the quality of coming undiluted and fundamentally even unmediated — from a personal insight that he neither contrived nor could edit. I dislike [Lionel] Trilling’s specious “reasonableness” — I fear it; for behind this air of prudent good sense and modest tentativeness, I always feel the presence of someone who is trying to arrange a “structure,” rather than trying to get a fundamental point made and said.

For this reason, the journal may have been Kazin’s ideal medium — a place where he could pursue “self-communion” without worrying about self-contradiction or reproach or a word limit. He was a faithful diarist his whole adult life, filling some 7000 pages, and Richard M. Cook’s thoughtful selection reads like an autobiography written in real time. There’s less artifice than in Kazin’s three fine memoirs and more voice and interiority than in Cook’s laudable biography of 2007.

Clearly, Kazin also prized his journals as a release valve: “They all outrage me; the sanctimonious [Sidney] Hook and the idiotically smug Stalinists, and the crooked Nixon.” Sometimes his candor can be cringe-inducing: “The deliciousness of the married woman, taking literally what belongs, or had belonged to someone else!” But when Kazin allows himself to be needy or petty or covetous, it’s often an attempt to come to terms with these parts of his personality. He was aware of the tension between his public and private selves: “I am a critic-teacher-authority to so many, but to myself, a raging id, a volcano of passions.” The journals helped him to see these two aspects of himself as related, because he was seeking the same thing in his public and private lives, in literature and in sex: “Anything with the touch of real transcendence in it wins my heart.”

Born in 1915 to Russian immigrants, Kazin grew up in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn when it was still both a Jewish slum and a suburb, full of new tenements, old farmhouses, and vacant lots, a childhood he immortalized in his first memoir, A Walker in the City, which has now been in print for 60 years. His father was kind but remote and passive (although he introduced young Alfred to radical politics); his mother was loving, long-suffering, and overbearing, setting a precedent of codependence that would haunt all of Kazin’s relationships with women.

As a schoolboy he had a bad stammer, in response to which he developed a “tyrannical fluency.” Introverted and exceptionally smart, he graduated from high school at 15 and matriculated to City College. The earliest entries in his journals, which he began keeping a couple of years later, are all about big books and big ideas, and are tedious in the way that only teenage profundities can be, but also endearing: “Life calls us to nothing more than passionate and rigorously logical (truthful) introspection.” When reading the great novelists, Kazin clearly felt he was communing with his intellectual peers: “The ‘Epilogue’ to Crime and Punishment is . . . one of the most beautiful and impressive scenes in the whole of fiction,” he wrote, a couple of months after his 18th birthday. The whole of fiction!

Within 10 years, Kazin had completed a master’s in English literature at Columbia, become literary editor of the New Republic, and published On Native Grounds (1942), a reconsideration of American realist fiction that made his reputation as a critic. Now the great writers were his peers, and a parade of marquee names began marching through his diaries: Malcolm Cowley, Hannah Arendt, T. S. Eliot, Isaiah Berlin, Ralph Ellison, Sylvia Plath, Saul Bellow, Elie Wiesel, Susan Sontag. By his mid-20s, Kazin had also come into his mature writing style, and it is the most distinctive thing about this book. He doesn’t tell stories very often, or very well (he admits that for a literary critic he has no sense of plot), but he lives to work through an idea until he has worked it out:

Whenever I had a chance, I kept at [Thomas] Merton’s autobiography, The Seven-Story Mountain; moved me so deeply that I got a little scared at one point that I was falling back into my old abject jealousy of les religieux again. But it seemed to me as I stood there on the porch, thinking hard and close on it, that the real reward of such a book is not in the discovery or rediscovery of Catholicism, which is fundamentally not important to the book, but in Merton’s own quality. In sum: and a good thing to get clear in my head for once: not the creed, but the believer.

Though not an observant Jew, Kazin revered religion and reviled its stand-in: ideology. In a sense, the search for understanding was his religion, and he conducted it, on the evidence here, largely in good faith. The sincerity of the effort is witnessed not only by the persistent self-criticism, but also by the lack of glibness in the writing.

Not that Kazin couldn’t deliver a bon mot when he wanted to. Something about recording impressions of people, particularly, concentrated his mind and his writing. On Jacques Barzun: “He manufactures sentences, he emits thoughts, with a proficiency that I find deadly. I keep trying to imagine him in his underpants, but it is impossible.” On Hannah Arendt: “She is so slow, often, on the ‘pick-up’ simply because she cannot really imagine what [it] is for anyone else to be unnatural.” But when grappling with someone’s writing, Kazin would often take several passes at an idea, really trying to get it right rather than merely to make it sound right.

Kazin may be easier to admire from a reader’s distance than from up close. He tended to grow restless in relationships, personal and professional, and his marriages usually lasted about as long as his academic appointments — although in both cases the last ones stuck (CUNY and Judith Dunford). Kazin also grew estranged from many of his important friends, although politics and personality made that difficult to avoid. Like most Jewish intellectuals of his generation, Kazin had grown up with socialist sympathies. But he was wary, too, of political commitments: He never joined the Communist Party and was an early anti-Stalinist. Nor, later in the century, did he follow his disillusioned former comrades in their migration to the right — their new certainties bothered him just as much as their old ones had: “Letter from Sidney Hook in this morning’s Times explaining that the peace movement assists Communism. Mr. Hook is one of those people who long ago learned the art of sounding positive, about anything he thinks at the moment. The crusades change, the crusader never.” His old friend Saul Bellow, whose body of work Kazin revered, never fully forgave him for a negative review of Mr. Sammler’s Planet. Kazin was no good at keeping opinions to himself, and when faced with a choice between loyalties to his opinions or to his friends, he lost friends.

He also, pretty clearly, lost some friends simply because he was exasperating. In early 1968, Kazin reported the following encounter:

At Elly Frankfurter’s party . . . [Norman] Mailer in his lapelled vest, jutting ex-pug belly, and inhuman actor’s look of “taking it all in,” annoyed me so much that I said some very rough things to him. I said he looked like a pig, and he did. A pig of American prosperity. But I realize now that Norman’s inhumanness is that he is always nothing, a blank on which his mind is writing some new part for him to play and that the method of incessant confrontation which makes up the scenario of [Armies of the Night] is his extraordinary way of locating and dramatizing.

Kazin includes his own hateful words in the service of a larger point about Mailer’s writing. The reader further learns in a footnote that Mailer had responded by challenging Kazin to a fistfight — a detail so peripheral to Kazin’s point that he didn’t think to include it. For Kazin, literature was primary. It’s hard not to love that about him, however hard he may have been to love. The day after his first wife left him, he mentioned it in his journals, but only after a few sentences of praise for the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, whom he was reading at the time: “The really extraordinary thing about Whitehead is his feeling for eternity,” Kazin wrote, in the first hours of his new life alone. “He is in the celestial halls.”