In “Love of Mother, Glory of Crown,” an essay in the Winter 2010 issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review, Robert Cohen ’83SOA examines the return of the Axum Obelisk, an ancient stele that was plundered during Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia and installed in Rome. Asked by a blogger for the magazine what drew him to the obelisk and Ethiopia, where he and his wife adopted a 10-year-old AIDS orphan, he explains, “It just so happens that mixed feelings and tangled motives and the serio-comedy of futile, intractable projects — this is the sort of thing that interests me.”

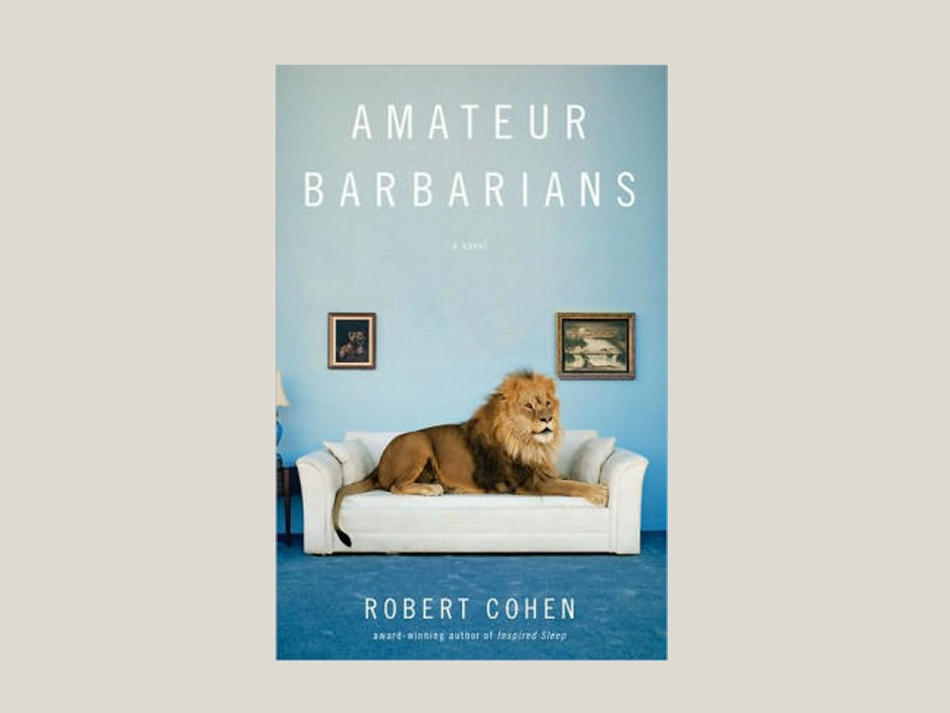

Cohen pursues those same hybrid interests in Amateur Barbarians, a tender send-up of civilization’s discontents. Though it concludes in the Horn of Africa, his fourth novel begins in fictional Carthage, a small New England college town not unlike Middlebury, Vermont, where Cohen is a professor. In addition to its “eight churches, one movie theater, four restaurants, one supermarket, and two state-run liquor stores,” Carthage contains one restless middle-aged educator.

In the opening sentences of the book, 53-year-old Teddy Hastings, the principal of Carthage Middle School, is running on the treadmill in his basement. Shaken by the death of his younger brother Philip, and made restless by British explorer Wilfred Thesiger’s Danakil Diary and his own 20-year-old daughter Danielle’s adventures in China and elsewhere, Teddy becomes unhinged. He snaps at his wife and his other daughter, and he behaves boorishly at a dinner party with friends. After a series of blunders lands him in the county jail and leads the school board to provide a compulsory sabbatical, Teddy flies off to Africa, the unhappy hunting ground of lost Americans intent on saving the world.

As a foolish foil, Cohen offers Oren Pierce, a 31-year-old Proteus who craves the routine that Teddy flees. By the time he arrives in Carthage in pursuit of a woman who dumps him and leaves town, Oren — a vagabond who has dropped out of programs in law, film, rabbinical studies, and social work — is ready for conventional restraints: “His faith in freedom was broken; he wanted to be bound by other people’s schedules, live the unfree inflexible life, like everyone else.” In a narrative strategy that is so flagrantly manipulative it must be part of the farce, Cohen has Oren take over Teddy’s job, as well as his wife.

A seatmate on Teddy’s flight across the Atlantic quotes Ugolino della Gherardesca’s speech from Dante’s Inferno: “Io non mori, e non rimasi vivo.” Teddy does not understand Italian, but the reader realizes that Teddy, like Ugolino, is neither dead nor alive. With its emphasis on middle-aged, middle-class characters who teach in a middle school, Amateur Barbarians is a comic study of the attractions and frustrations of la via media. Following a cancer scare, Teddy describes himself as “in the middle. Somewhere between okay and scared to death.” He is yet another literary victim of midlife crisis, and his way of coping with it echoes the trajectory of Eugene Henderson, the impulsive schlemiel in Saul Bellow’s 1959 novel Henderson the Rain King, who insists, “I want, I want, I want!” Teddy’s journey by caravan into the arid reaches of Africa makes one think of Paul Bowles’s Western travelers transformed by an unmediated encounter with barbarian others.

If this book is about “amateur barbarians,” middle-class Americans who recklessly abandon their moorings, then who are the professional barbarians? Wrestlers? Investment bankers? Writers? Cohen is adept enough at the writer’s craft to make the tired theme of male menopause not seem tiresome, mostly through a perky style. He is particularly fond of striking similes. After a reluctant conversation with Teddy, a mysterious stranger “zipped her face shut like someone putting away a cello.” The ghost of Teddy’s brother Philip “floated like a thought bubble over the comic strip of the days.” Elsewhere, we are told that “his stomach was rioting like a cellblock.” He will later savor a sample of the local delicacy: camel’s hump.

A preposterous episode in which Chinese aliens are apprehended in Carthage is an artistic misstep, and a reader can be as impatient as Teddy is with details of domestic life in small-town New England. The novel is most alive when it leaves American soil. About two-thirds of the way through Amateur Barbarians, a stranger complains about travelers’ tales she has had to put up with: “So many stories and confessions. Everyone shares their little heartbreaks.”

“Want to hear some of mine?” asks Teddy. “I’ve got enough for a whole book.”

She replies: “Forgive me, but I think no one wants to read such a book, if I may be honest.”

I have, with pleasure, read such a book, a seriocomedy of futile, intractable projects.