New Yorkers Graham and Audra have a life that looks pretty perfect from the outside. He’s an attorney. She’s a part-time graphic designer and full-time mom to their gifted ten-year-old son, Matthew. Their apartment is lovely, their schedules are full, and they even seem to (mostly) find each other charming after twelve years of marriage.

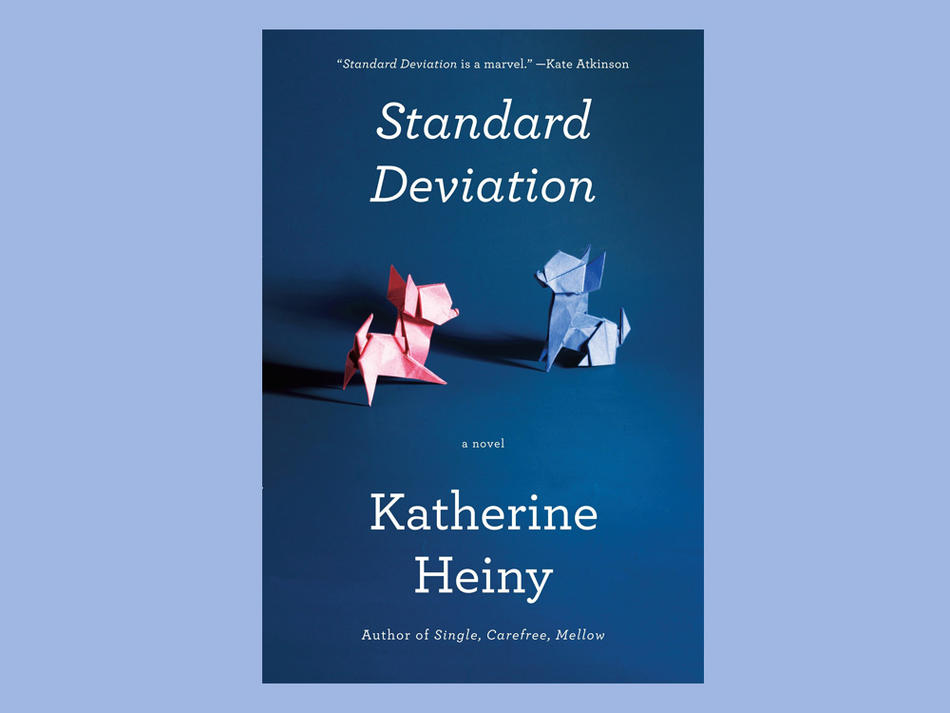

But, of course, in Katherine Heiny’s novel Standard Deviation, it doesn’t take long to discover that all is not, in fact, perfect. Audra is Graham’s much-younger second wife and his former mistress, a fact that still causes some guilt and awkwardness in their marriage. And Matthew, a quirky, friendless, origami-obsessed child, has recently been diagnosed with a developmental disorder on the milder end of the autism spectrum.

Heiny ’92SOA writes tenderly about the different ways that Graham and Audra navigate parenting a special-needs child. It’s clear that Graham loves Matthew, though he still sometimes wishes that he could trade him for a child who can make friends easily and roll with life’s punches. These parental frustrations are hard for Graham to accept, because he isn’t exactly socially gifted himself — he can be sarcastic and grumpy and a little too fond of routine and order.

Audra, on the other hand, is so cheerful and easygoing that she could, as Graham says, “make friends with a statue.” She’s nurturing and endlessly patient with Matthew. But she also has no boundaries: she makes a habit of taking the lonely and displaced under her wing and, in many cases, into the family’s apartment. Even Graham is surprised when Audra very quickly manages to make friends with his ex-wife, Elspeth (on whom Graham cheated with Audra twelve years earlier). Thanks to Audra’s social prowess, the humorless Elspeth and her foppish boyfriend, Bentrup, become the couple’s regular dinner companions, and all social norms seem to fly out the window.

Heiny, a graduate of the School of the Arts in fiction and poetry, was praised as something of a literary virtuoso in 1992 when she published her comic short story “How to Give the Wrong Impression” in the New Yorker at age twenty-five. She left the literary scene for twenty years to raise a family, but her prose here feels as fresh and funny as it did then, especially thanks to her vivid use of metaphor. Walking an unruly dog is like “flying a kite in a hurricane.” Audra’s attempt to climb from the back of a car to the front feels to Graham “like a giraffe [is] being born next to him.”

Standard Deviation is not a plot-driven novel, and it can meander at times. But as a comedy of manners, it works beautifully. Graham, Audra, and Matthew are wonderfully flawed, and in the end that makes them easy to root for.