Julie Otsuka ’99SOA opens The Buddha in the Attic with an epigraph from the apocryphal biblical work Ecclesiasticus: “And some there be, which have no memorial; who are perished, as though they had never been.”

Her short, precise, poetic novel, nominated for the 2011 National Book Award, aims to correct this melancholy situation for one such forgotten group — the Japanese “picture brides” who journeyed to California in the early twentieth century. Often relying on outdated or otherwise deceptive photographs and letters, they left everything they knew in order to wed Japanese laborers and farmers they had never met.

Otsuka writes in the unusual first-person plural, interspersed with apparent quotations from historical and autobiographical sources. Combining epic sweep with telling detail, she recovers these women’s sacrifices, their American lives, and the memories they left behind in a narrative that is wistful, elegant, and, in the end, perhaps deliberately unsatisfying.

The book begins with the guarded optimism of the brides-to-be venturing toward their linked but disparate fates:

Most of us on the boat were accomplished, and were sure we would make good wives. We knew how to cook and sew. We knew how to serve tea and arrange flowers and sit quietly on our flat wide feet for hours, saying absolutely nothing of substance at all . . . We knew how to pull weeds and chop kindling and haul water, and one of us — the rice miller’s daughter — knew how to walk two miles into town with an eighty-pound sack of rice on her back without once breaking into a sweat.

These women, so well-meaning and so naive, would need many of these skills and unforeseen others besides. But most important would be their capacity for endurance. On their first night in America, Otsuka’s narrator, who is at once omniscient and implicated in the actions she describes, depicts the brutality of the marriage bed:

That night our new husbands took us quickly. They took us calmly. They took us gently, but firmly, and without saying a word . . . They took us greedily, hungrily, as though they had been waiting to take us for a thousand and one years. They took us even though we were still nauseous from the boat and the ground had not yet stopped rocking beneath our feet.

After these shocking introductions to their stranger-husbands, the picture brides would face the more mundane challenges of carving out a living in a new country. Most of the men they married were poorer than advertised, and they put their wives to work, often for abusive white employers, as domestics or farm hands. The relationship between the Japanese immigrants and their white neighbors was emotionally complex: “We loved them, we hated them, we wanted to be them.”

At home, the picture brides, however tired, faced the inevitable second shift, cooking and cleaning and, eventually, caring for children. The men “never changed a single diaper” and “never washed a dirty dish,” Otsuka writes, using lyrical prose to tell a homely story. The husbands “sat down and read the paper while we cooked dinner for the children and stayed up washing and mending piles of clothes until late.”

The children, who might have brought joy, certainly brought heartache. If they didn’t die in infancy, they grew up, like most immigrant offspring, to reject Old World traditions and embrace American ways. “They gave themselves new names we had not chosen and could barely pronounce,” Otsuka writes. They forgot the Japanese language and Japanese gods and acquired American-sized ambitions. Still, their mothers nurtured them: “Even though we saw the darkness coming we said nothing and let them dream on.”

This is Otsuka’s masterfully delicate foreshadowing of the historical cataclysm that would shatter the acceptable rhythms of so many lives. The bombing of Pearl Harbor unleashed an anti-Japanese hysteria, a dismal outpouring of American xenophobia amped up by the war in the Pacific.

Otsuka chronicles the encroaching threat to Japanese-American immigrants and their families, the rumors that began somewhere far away and moved ever closer. However stark their innocence, individual Japanese were detained, and disappeared. Fear haunted the community, along with hope that the threat would pass. When the deportation orders came, homes, businesses, and possessions were sold off at bargain-basement prices. The forced exodus to the now-infamous internment camps followed, brutally interrupting thousands of lives. (Otsuka’s 2003 debut novel, When the Emperor Was Divine, chronicled the life of one family in an internment camp.)

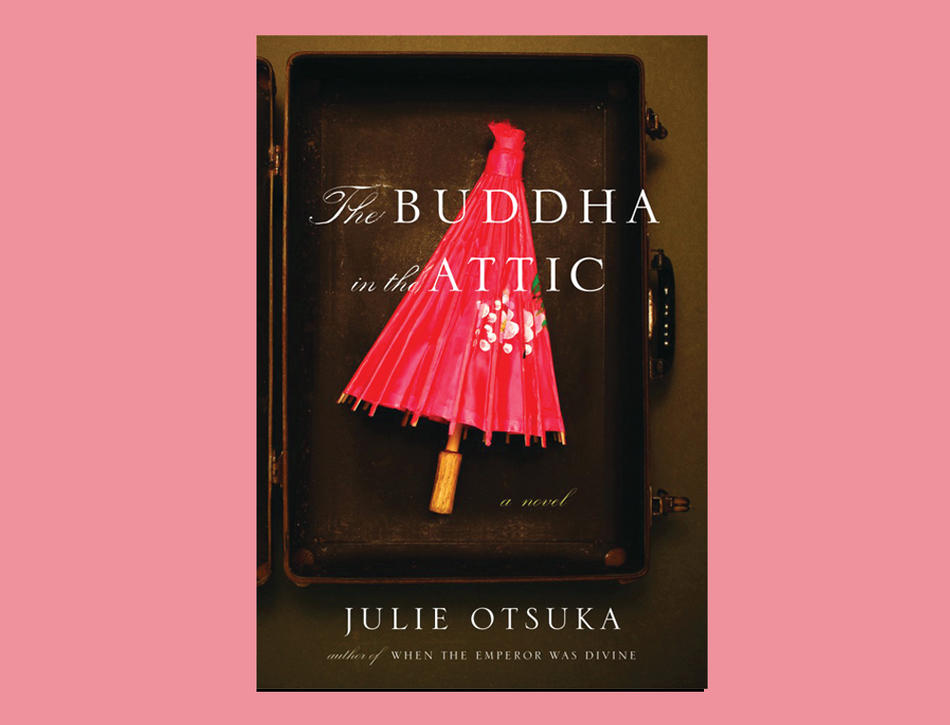

Otsuka’s sensual prose conveys the resulting tumult, as looters took advantage of the departures: “Most of us left in a hurry. Many of us left in despair. A few of us left in disgust, and had no desire ever to come back. Curtains ripped. Glass shattered. Wedding dishes smashed to the floor.” It is from the residue of the exodus that the novel draws its title. One of the brides, in her haste, left behind “a tiny laughing brass Buddha up high, in a corner of the attic, where he is still laughing to this day.”

The Buddha in the Attic challenges shibboleths about the American immigrant experience, illuminating some of its most troubling strands. And though the narrator predicts that “it would be only a matter of time until all traces of us were gone,” in fact the traces of this dark era arguably have remained, shaping Japanese-American — and American — culture.

The book ends with a startling narrative pivot, a choice to dispense with the potential drama of following the picture brides into the camps. Instead, in a chapter titled “Disappearance,” Otsuka shifts to the perspective of the whites, left to contemplate the boarded-up houses and overflowing mailboxes of their onetime neighbors. Where once there were dry cleaners, Japanese restaurants, and harvest festivals, there is now mostly quiet and absence, forgetfulness, and the vague lineaments of grief. We’re left with a slow ebbing of tension, the beginning of a long cultural silence that will, in time, be broken.