Writer, editor, and onetime Columbia lecturer Gordon Lish is famous for telling his students: “Don’t have stories; have sentences.” During workshops, the students took turns reading aloud to him until Lish lost interest and told them to stop. Many never made it past their opening line.

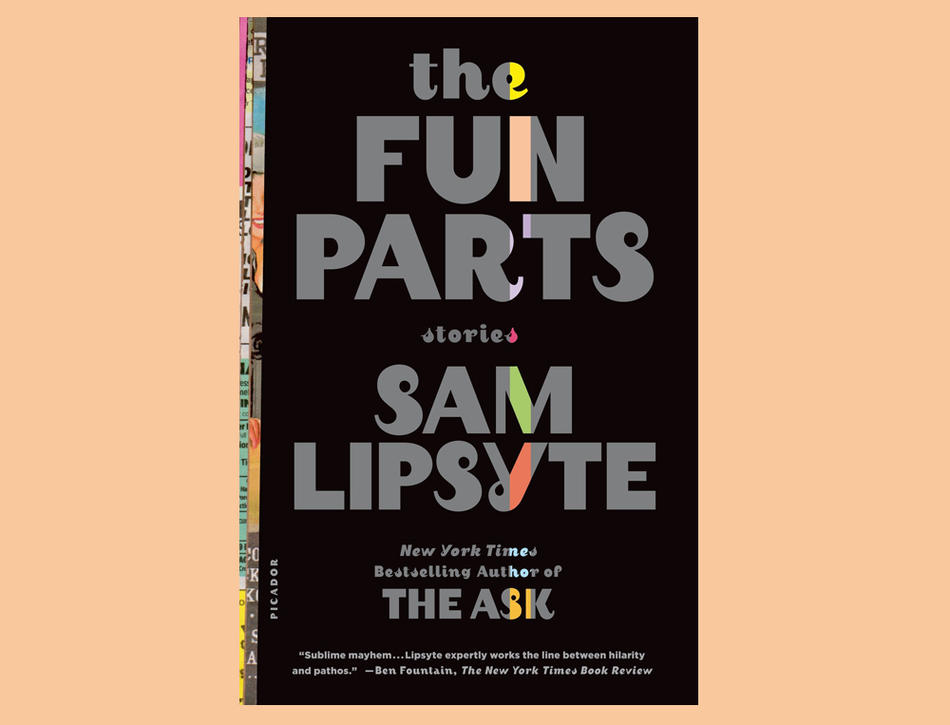

Harsh, maybe, but when heeded properly, Lish’s advice has produced greatness. One of his protégés, Sam Lipsyte, an assistant professor of writing at Columbia’s School of the Arts, is out with a new story collection, The Fun Parts, that is notable for its sentence work, perfect in its simplicity and charge. One story begins: “The Dungeon Master has detention.” Another: “Classic American story: I was out of money and people I could ask for money.” And another: “Davis called, told me he was dying.” These deceptively straightforward sentences are Lipsyte’s hallmark, even more so than his zany and often jovially obscene storylines, which usually get the glory. Of course, one would be nothing without the other.

None of these stories are being published for the first time; all thirteen have previously appeared in places like the New Yorker or Playboy and the Paris Review, but Lipsyte’s black humor, as much on parade here as in his four previous books, keeps them from feeling stale. Many moments had me spitting out my orange juice, even on a second read.

Lipsyte’s stories home in on losers at the periphery of society: Dungeons-and-Dragons-obsessed teens, a disillusioned high-school shot-putter, a drug-addicted cardio-ballet instructor, a male doula (excuse me: doulo), an earnest feminist writer working on her “poem cycles.” These characters are extravagant in their messes, their dependencies, their self-aggrandizement, their whining. They flail across the page, wild with masturbation and drugs and irresponsibility, steeped in self-loathing or inflated self-esteem or both. They are at times terrifying and even pitiable. Their chaos is contagious.

And yet. Lipsyte manages to endear us to these losers. Not all of them, and not completely, but they certainly come across better than the conventional “winners.” In “The Wisdom of the Doulas,” for example, the aforementioned doulo looks atrocious — he’s the “dude with the yellow teeth and the ratty (vintage) buckskin jacket.” But his employers, the Gottwalds, are worse — “uptight success types with their antique Ataris and sarcastic sneakers,” and we are not surprised when they name their newborn baby Prague.

The men of these stories are a particularly sad and tapioca-soft lot. If paired off, they generally play children to their grown-up wives, who have left or are in the process of leaving them, such as in the story “Expressive”:

“I want to save our marriage,” says my wife. “Do you want to save our marriage?”

“Yes,” I say. “Just not right now.”

“Get out.”

No one is left unscathed, certainly not children. In “The Republic of Empathy,” Peg explains to William that she needs another child because “this morning I smelled the top of Philip’s head. That sweet baby scent is gone. Now it just smells like the top of any dumbshit’s head.” Later, William tries to broach the subject with his toddler:

I took Philip for a walk. He tired easily, but his gait was significant. He tended to clutch his hands behind his back, like the vexed ruler of something about to disintegrate.

“How about a brother or a sister?” I asked.

“How about I just pooped,” Philip said.

Lipsyte is a satirist, but his stories capture something discouragingly real. After reading them, you’ll think worse of the person sitting next to you on the subway and even at your preschool board meeting, because Lipsyte’s world is full of “the angry and ex-decadent, the loading-bay anarchists and hackers on parole, the meth mules, psych majors.”

Story by story, deviancy begins to feel normal, and we see shades of these losers first in our neighbors and then, ultimately, ourselves; what starts as haughty laughter turns to a slow unsettling simpatico simper.