Few criminals have captured the public imagination like deranged killer Charles Manson. But when Manson and his cult of followers went on trial in June 1970 for the gruesome murders of seven people, the most haunting image in the media was not of Manson himself but of his three codefendants: Leslie Van Houten, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Susan Atkins. Lithe, fresh-faced, and shiny-haired, the girls — all in their early twenties — giggled and held hands as they were led into the courtroom, like they were off to a slumber party instead of death row. America watched in horror: these women could have been their daughters, their sisters, their neighbors. How could they have been led so far astray?

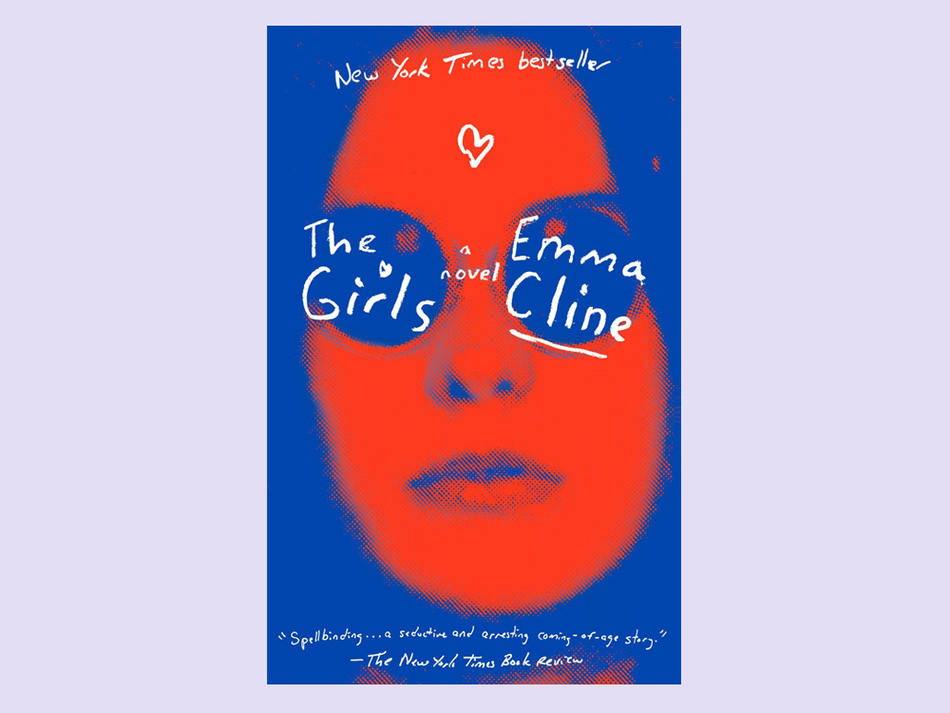

That question is central to The Girls, the deeply disquieting debut novel from Emma Cline ’13SOA. The book — which garnered a media frenzy of its own when Random House offered Cline a $2 million advance after a heated bidding war — follows a lonely teenager as she gets caught up in a thinly fictionalized version of the Manson cult. Suspense isn’t a key element — we first meet Evie Boyd nearly fifty years after the crimes that made the cult famous, and we know that she has escaped essentially unscathed. But following her, in flashbacks, from suburban banality to the brink of unspeakable violence, is gripping.

For fourteen-year-old Evie, the summer of 1969 — an “endless, formless summer” — is her last at home in a sleepy San Francisco suburb before being shipped off to boarding school. Her parents have recently divorced, and both are more interested in their new romantic relationships than in their daughter. Then Evie makes a social gaffe when out with a group of older boys that ends up costing her a crush and her best friend.

So Evie is lonely, and when she sees a trio of disheveled girls dumpster-diving for discarded food in a nearby park, she is intrigued. As she rides her bike idly around town, she starts seeing them everywhere. And unlike most of the other people in her life, they seem to see her too: “Back then, I was so attuned to attention. I dressed to provoke love, tugging my neckline lower, settling a wistful stare on my face whenever I went out in public that implied many deep and promising thoughts, should anyone happen to glance over.”

Evie’s nascent sexuality is important to the girls, disciples of a self-described guru named Russell, who deflowers Evie the first night he meets her. But she has something else integral to the group’s survival: money. Thanks to a small fortune left by her grandmother, a once-famous actress, Evie has grown up sheltered, on the right side of town, not wanting for anything. The cult has set up a makeshift commune on a llama ranch in the hills of Sonoma County, and apart from periodic gifts from a rich musician (perhaps a proxy for Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, a one-time benefactor of the Manson family), they are destitute. Evie starts staying with the cult most nights, and earns her keep buying basics like food and toilet paper; weeks later, the stakes get higher, and Evie is forced to prove her loyalty to her new world by more fully betraying her old one.

Cline borrows heavily from the Manson story, which undercuts the novel’s ability to be truly original, despite fresh, commanding prose. But Cline does make one crucial departure. By all accounts, Manson was the driving psychological force behind his cult; as Vincent Bugliosi, who prosecuted the Manson family, once said, Charles Manson “had a quality about him that one thousandth of one percent of people have.” For Evie, it’s not Russell — the Manson figure — that intrigues her, but Suzanne, one of Russell’s girls. It’s Suzanne’s embrace that Evie craves; and when Evie’s family eventually makes her return home, it is Suzanne who lures her back. As Evie says, “I couldn’t explain it to myself, the wrench I got from looking at her.”

Evie’s isolation and desperate need to belong are extreme, but Cline excels in making these traits relatable. The anguish of being a teenager is universal, and Cline captures that in perfect descriptions of Evie’s near-constant humiliation (at things she does, at things her parents do, at things her friends do). She knows the cult is dangerous, and yet she is so obviously relieved to be accepted somewhere that she can’t stop herself from going back.

It’s easy to empathize with the teenage Evie. But this is not just a story about the recklessness of youth. When we encounter Evie again as an older adult, her emotions about the cult are still unsettlingly complex. Mixed in with guilt and sorrow, there is, unexpectedly, a twisted nostalgia: “Some nights, unable to sleep, I peeled an apple slowly at the sink, letting the curl lengthen under the glint of the knife. The house dark around me. Sometimes it didn’t feel like regret. It felt like missing.”