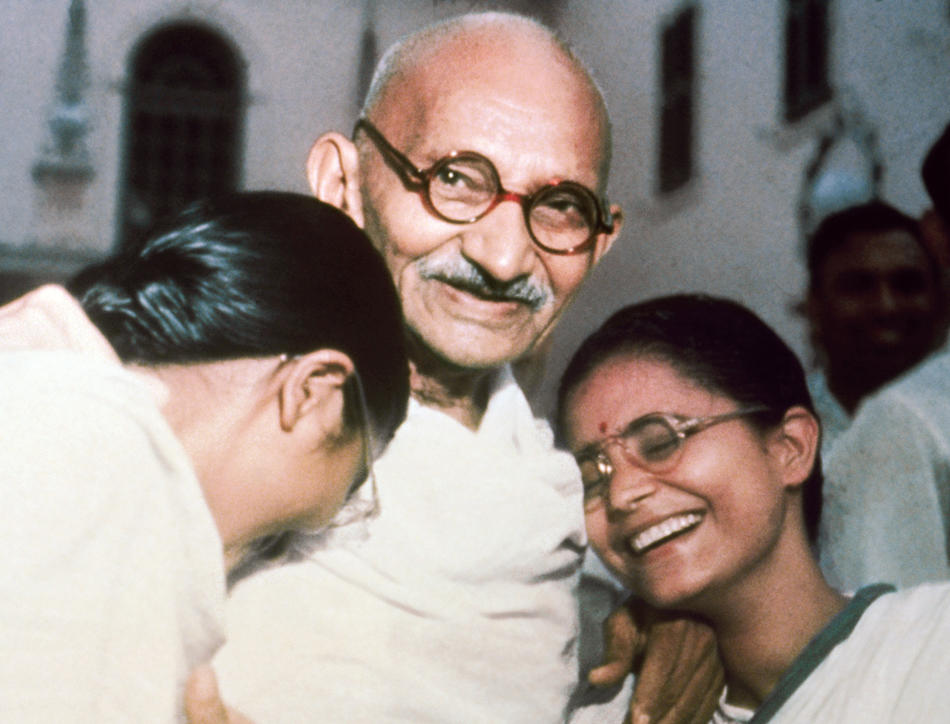

A few months before his death in 1948, Mahatma Gandhi remarked that men like him must be measured “not by the rare moments of greatness in their lives, but by the amount of dust they collect in the course of life’s journey.” Few of the hundreds of Gandhi’s biographers have followed this dictum, choosing instead the safe comfort of hagiography. Pulitzer Prize winner Joseph Lelyveld ’60JRN, former executive editor of the New York Times, puts the record of Gandhi’s life to Gandhi’s test. The result, Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India, is a hard-edged, grainy, but cogently persuasive biography of one of the most illustrious figures of the 20th century.

The subtitle reveals Lelyveld’s key idea: Alongside his well-known political struggle for India against British colonial rule, Gandhi carried out an even more determined struggle with the country of his birth, or at least with all of those things he believed were wrong with it. Gandhi’s list of complaints about the ills that plagued Indian society did not come to him ready-made. He chopped and changed the list, shifting priorities, learning from his experience and making new discoveries — having, as Lelyveld remarks somewhat acidly, a moment of epiphany every two years or so. But once he decided to launch a struggle against a retrograde practice, whether a gigantic one, such as caste discrimination or sectarian violence, or something mundane concerning habits of personal hygiene, he would set himself the most severe trials and present his own ordeal as an example for everyone else to follow. When he campaigned against the persecution of dalits — untouchables — he would perform, and make his family and close associates perform, the lowly job of the scavenger; when preaching peace in the middle of sectarian violence, he would disregard saner advice and take extreme risks with his own safety. He did not always have perfect clarity in identifying his targets and, as Lelyveld shows with meticulous analysis, the results of his campaigns were often mixed. But Gandhi’s ceaseless efforts to learn from his “experiments with truth” were a journey of striving to rise above his received inheritance of class, caste, race, and religion.

Gandhi spent 21 years as a lawyer in South Africa before leaving for India on the eve of World War I. Lelyveld’s research into this period reveals much that has been papered over by later mythmaking. Gandhi’s political career began in South Africa with his efforts, mostly through appeals and petitions but soon shifting to more unconventional tactics, to win legal equality for Indians with whites. The Indians he was concerned with were mostly merchants and professionals. Lelyveld shows that not until his last campaign in 1913 — a strike by Indian coal-mine workers, joined by indentured laborers in sugar plantations — did Gandhi seriously engage with the problem of including low-caste Indians within the domain of equal rights. When he did, it was by the prompting of his own discoveries about the wretched lives of untouchable migrant workers and not because of any doctrinal adherence to abstract theories of human equality. What is troubling, however, is that Gandhi kept himself thoroughly apart from the African people and their struggles: His casual remarks about “the kaffirs” show nothing more than the received prejudices of his own upbringing.

The unprecedented mix of religious idiom, ethical practice, and tactical skill that Gandhi brought into modern politics has perplexed many. One of his most controversial fasts-unto-death was launched in 1932 over certain abstruse voting rules for the so-called “depressed classes” in the new constitutional reform proposals. In truth, the contest was about who could legitimately speak on behalf of India’s untouchables: the erudite B. R. Ambedkar ’15GSAS, ’27GSAS, who was an untouchable, or Gandhi, an “untouchable by adoption,” as he called himself. In a furious test of wills, Ambedkar gave in, at least for the time being. But Gandhi’s victory, as Lelyveld shows, if not quite Pyrrhic as far as his hold over the national movement was concerned, had little effect on the real lives of the untouchable castes.

One by one, Lelyveld homes in on those moments in Gandhi’s life that shine with his greatness — the amazing transformation he brought about in the Indian National Congress, taking it from a genteel annual gathering to one of the largest mass movements in the world; his rousing successes and heroic failures with Hindu-Muslim amity; his fight against untouchability; his last desperate bid to prevent the partition of the country — and points to the underlying tensions, vacillations, and retreats, the bluff and bluster, the hard bargains, the frequent emotional blackmails, but also Gandhi’s unshakable resolve never to spare himself from criticism and punishment. Was Gandhi a saint who had unwittingly strayed into politics or was he in fact a supremely Machiavellian politician who cleverly donned the mantle of morality when it was convenient? Lelyveld takes seriously Gandhi’s many personal fads and idiosyncrasies but does not fall into the easy trap of suggesting psychological solutions to the political puzzles posed by a saintly life. As a biographer faithful to the available records, he admits that many of these enduring questions cannot in fact be satisfactorily answered.

The reticence to judge after presenting the evidence is, unfortunately, not a guarantee against self-appointed jurors who are itching to condemn or absolve. Alongside Gandhi’s surprising avoidance of Africans, Lelyveld also discusses, with jocular indulgence, the great man’s relationship with Hermann Kallenbach, the Jewish architect who was his closest friend in South Africa. Soon after the publication of the book, a reviewer in a British daily declared that Lelyveld had proved that Gandhi was a racist homosexual. Within days, the news traveled to India. The government of Gandhi’s home state of Gujarat, unwilling to take chances with fomented passions, immediately banned Lelyveld’s book, even before it had arrived.