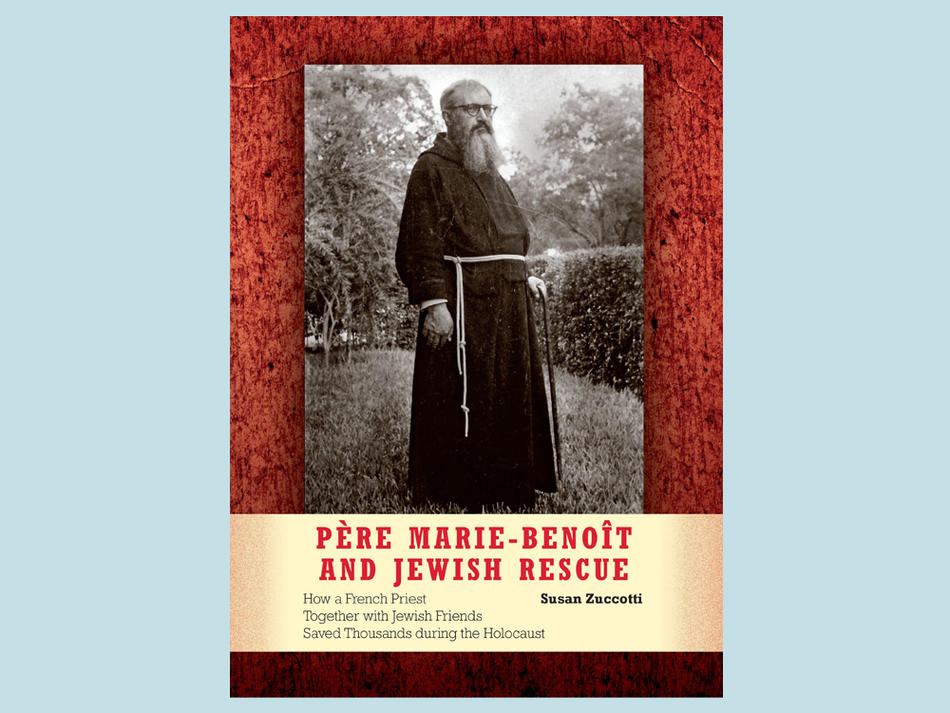

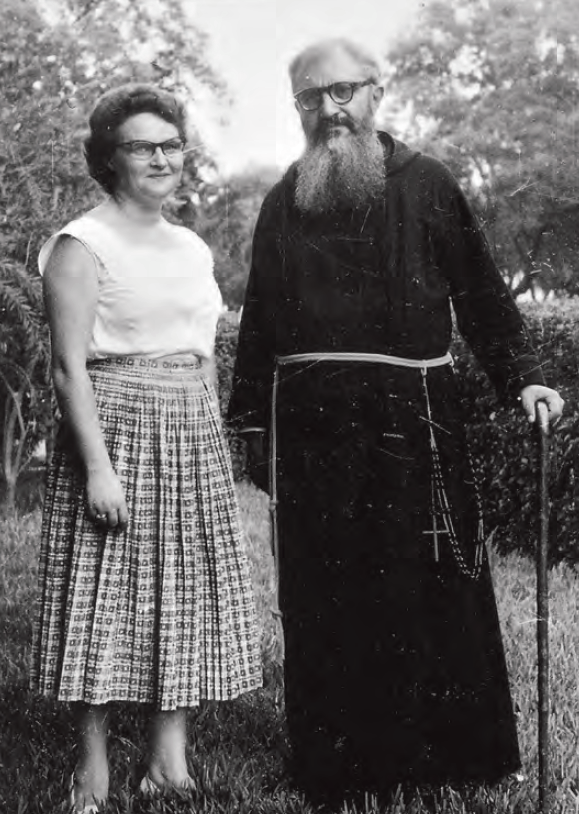

Père Marie-Benoît — or Padre Benedetto, as he was known in Italy — was a big, untidy man with a sprawling beard and the brown cassock and sandals of his Capuchin order. He was wry and humorous and greatly loved by his friends. More than that, he was brave and imaginative, and spent the years of the Second World War in France and Italy leading and taking part in the rescue operations of Jews from the Nazis. With Père Marie-Benoît and Jewish Rescue, Susan Zuccotti ’79GSAS, who has written several distinguished works on the Holocaust in both countries, returns to the archives to dig out a mass of fascinating material on a man who has been neglected by historians.

Born in 1895 as Pierre Péteul to a modest family in a village near Angers in western France, Père Marie-Benoît was moved as a boy by the tales of the harsh treatment of the Catholics during the French Revolution, and by the emphasis on poverty and austerity he observed in the Capuchins. The order provided him with an education that he would not likely have received otherwise, and after he served as a volunteer stretcher bearer in the First World War, they sent him to Rome in 1922 to earn a doctorate at the Gregorian University. Mussolini and the Fascists were gaining power, and the streets rang to the sounds of marching squadristi. For the next eighteen years, he stayed on to teach young priests. When Italy declared war on France, in June 1940, he moved to Marseille, but not before witnessing the publication of the Manifesto of Racial Scientists and hearing Mussolini declare that Jews did not belong to the Italian race. Père Marie- Benoît did not see it that way. For him, these were shocking words.

The southern coast of France remained a place of relative safety for Jews even after the Germans moved south into most of what had been the nonoccupied zone in November 1942 and the Italians occupied ten French departments and the cities of Nice, Cannes, Valence, Grenoble, and Vienne. The Italians, unlike the Vichy French, did not choose to turn over their Jewish citizens and refugees to the Nazis. Officials sent from Rome to expedite deportations dragged their feet. Even so, the Jews needed hiding places and false documents, and Père Marie-Benoît set about providing them.

He was fortunate in meeting two other remarkable figures, a Russian businessman and lawyer, Joseph Bass, known to his friends as “l’hippopotame” on account of his girth, and an Italian banker and diplomat, Angelo Donati. (Whether he met and worked with the third determined saver of the Jews in the south, the Syrian writer Moussa Abadi, who had set up a similar rescue operation in Nice, Zuccotti does not say.) Between them and their helpers, the three men worked feverishly and successfully, at least until Mussolini fell at the end of July 1943. General Eisenhower had agreed to wait a few days before announcing the new Italian prime minister Pietro Badoglio’s unconditional surrender; when Ike jumped the gun, German troops poured south before there was time to make plans to get the Jews over the border into Italy. Not least of the many fascinating parts of Zuccotti’s book are her detailed descriptions of Donati’s negotiations with the Allies and the Italian government. Donati, she writes, wore many hats, as a banker, community leader, philanthropist, and man about town.

By September 1943, Père Marie-Benoît was back in Rome, joining forces with DELASEM, the Delegazione per l’Assistenza degli Emigranti Ebrei, a similar Jewish rescue operation. From then until the summer of 1944, he was constantly on the move, transferring Jews from one safe house to another, delivering medicine and money and false documents. May 1944 was a lethal month: two French deserters betrayed the rescue operation to the Germans, and the Jews subsequently rounded up were on some of the last trains to Auschwitz.

Zuccotti is evenhanded — some might say generous — about the conduct of Pope Pius XII, whose attitude toward the Jews in Italy was at best ambivalent and whose public statements seldom touched on anything more specific than the need to “show compassion” toward victims of war. She was able to meet Père Marie- Benoît in 1988, and made contact with his surviving friends. In archives across Italy and France, she unearthed much information about the deals and subterfuges brokered by Père Marie-Benoît and DELASEM in their negotiations with the Vatican and the various foreign ambassadors residing within its walls, and about the gestures, for both good and ill, made by individual prelates. It is seldom an edifying story.

Père Marie-Benoît was ninety-four when he died, back in Angers, in a Capuchin home for the elderly. Much honored by the French, the Italians, and the Americans, and named a Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, he rose to the positions or jobs he may have wanted, and it was said that his lifelong attachment to the cause of friendship between Jews and Christians did not endear him to the Vatican or to his superiors. Zuccotti’s fine book about this modest man, who may, together with his friends, have been responsible for saving some 2,500 people from the Nazis and deportation, shows how much could have been done, had there been the political will and the courage to do it.