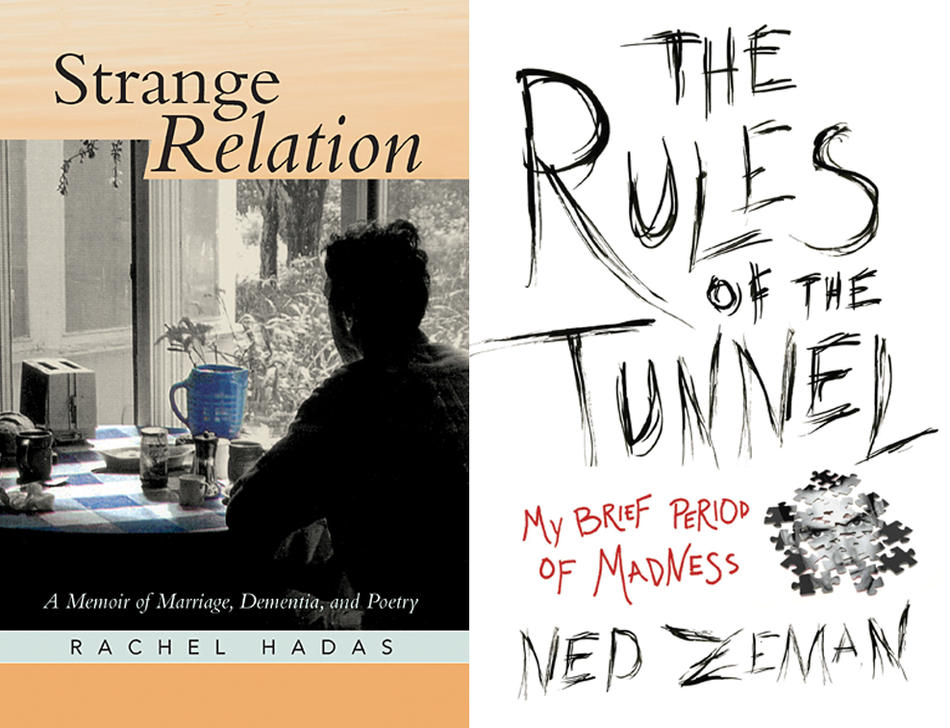

It takes bravery to expose the darkest psychological crevices of one’s life. True, nowadays that sort of courage is not in short supply. Candid memoirs of mental illness, dementia, and family dysfunction crowd bookshelves, and authors offer their souls for sale on talk shows and Twitter. Still, recent books by Ned Zeman ’88JRN, a Vanity Fair contributing editor, and Rachel Hadas, a poet and Rutgers University professor who taught at Columbia in the early 1990s, are worth singling out for the stories they tell and the ways in which they stretch the memoir form.

The Rules of the Tunnel is a witty, sometimes farcical, often elegant, and occasionally confusing account of Zeman’s descent into what he calls, optimistically, “my brief period of madness.” His demons include depression, amnesia, and a predilection for the wrong women. The narrative, a jumpy, nonlinear account of Zeman’s life on both sides of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), is entirely in the second person. It’s a device, forced at times, that seems to signal the author’s alienation from his own psyche, an especially remote reportorial objectivity, or both.

Strange Relation is Hadas’s tale of her husband’s encroaching dementia, and of the losses and challenges that ensue. The man in question is George Edwards, a composer and professor of music at Columbia from 1976 to 2008. Like Zeman, who kept a journal, Hadas used language to impose order on a life spiraling out of control. Her first resort is poetry, her own and others’. (The title is drawn from a Wallace Stevens poem, “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction.”) Hadas frequently situates her ordeal in the landscape of myth, comparing her fate to that of Homer’s Penelope, who weaves and unweaves her creations while awaiting her husband’s unlikely return. But Hadas, unlike Penelope, waits in vain. (Hadas is the daughter of the esteemed classics professor Moses Hadas ’30GSAS.)

Zeman’s catastrophe may lack the grandeur of tragedy, but it is not without tragic elements. Apart from his mood disorder, he is plagued by social anxiety and seems to lack the maturity to find a life partner. One girlfriend compares him to a seven-year-old, which — like other unflattering observations — he dutifully reports. In many respects, though, Zeman is a fortunate guy, blessed with a loving family, intensely loyal friends, ex-girlfriends who still worry about his well-being, and a job at one of America’s premier magazines.

Zeman’s account of his bewildering first day as an editor at Vanity Fair is at once precise and satirical:

Figures materialized out of nowhere, forming a natural ecosystem. At the center of the system were platoons of copy editors (“it’s composed, not comprised”) and fact checkers (“Camilla used brands other than Tampax”) in hot, futile pursuit of the top-shelf editors. The latter were too busy talking their writers off the ceiling (“I’m aware you drank with Hemingway, but this paragraph still needs to go”).

Eventually, Zeman, who is just 32, is introduced to his first writer: Carl Bernstein. Bernstein calls him Ted and asks for a Diet Coke. Running this errand, Zeman misses an imperial summons from Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair’s ruling eminence.

From there, life at the magazine can only improve, especially once Zeman starts filching stories destined for his writers. He makes his mark with chronicles of doomed, driven geniuses in love with penguins and grizzlies, who meet seemingly inevitable wilderness deaths. He is drawn to these stories of mania and obsession, even as his own mental health declines.

After a stint in New York, Zeman returns to Los Angeles as a Vanity Fair contributing editor, writing both celebrity features and his signature tales of doom. But when clinical depression lays him low, a battery of meds, shrinks, and hospital visits doesn’t work, at least not well enough. Even a stay at the elite private-pay McLean Hospital, near Boston, the facility favored by Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, and other tortured poets, isn’t a sufficient jolt to his system.

He finally decides on ECT, the treatment of last resort for depressives. Short-term memory loss is a common side effect, but Zeman’s side effects turn out to be more severe: He loses a year or more of his life, forgetting everything. And his depression cedes to hypomania, causing him to drive, date, and berate his nearest and dearest with equal recklessness. He can’t remember, and he lies about what he does remember. Then he can’t remember his own lies. The manic episode may signal that he is bipolar, but doctors disagree on his diagnosis.

While the patient pursues recovery, the writer tries to recover his own story from the fog of amnesia. As his madness and short-term memory problems subside, Zeman interviews friends, peruses e-mail trails concerned with his fate — and discovers what a jerk he has been (shades here of David Carr’s 2008 addiction memoir, The Night of the Gun). It’s not always clear in the narrative just how Zeman knows what he knows.

“Good luck finding a miserable amnesiac,” Zeman writes in his sardonic, self-deprecating prologue. But he realizes he has lost something because he feels its absence. “The heart,” he tells us, “remembers what the mind forgets.”

Hadas, unlike Zeman, enjoys the gift of a mostly happy marriage, punctuated by classical music and companionable silence. Over time, though, as her husband’s mental faculties decay, a different silence develops, and she undergoes the privation of “living with, eating with, waking up next to someone who has nothing to say to you.”

Hadas leads the reader gently, eloquently, through the terrors of such a life. Edwards’s decline is gradual; he is not diagnosed until 2005, at age 61, but Hadas (56 at the time) believes in retrospect that his symptoms were first detectable six years earlier. As with Zeman, diagnosis is an issue: Hadas is still not sure whether Edwards suffers from frontotemporal dementia (FTD) or an atypical variant of Alzheimer’s disease. In either case, however, there is no cure. Edwards, forgetful and confused, must end his teaching career in 2008; he eventually stops composing, playing the piano, using the phone, interacting with the world. He still walks, eats, smokes. A friend analogizes him to “a giant hamster.”

With the help of aides, and occasionally the couple’s grown son, Hadas cares for her husband as long as she can at home before finally seeking an institutional placement. She draws insight from dementia memoirs and comfort in “the sustaining power of literature,” which she reads with new understanding. In lines by Greek poet C. P. Cavafy — “With no consideration, no pity, no shame, / they have built walls around me, thick and high” — she sees a description of a progressive, incurable disease. She writes her own elegiac poetry about a man who “has never really left,” and yet “is also long and gradually gone.”

Hadas’s excursions into literary quotation and analysis add an intellectual dimension to a by-now-familiar tale, but they also blunt its narrative drive. It’s as if she is willing the deterioration to slow by stopping to ponder it.

Edwards himself is the one source who has little to say about his illness, but what he says pierces the heart. “I’m so sorry to visit this on you,” he tells Hadas. And then, once: “I’ve been very lucky.” Hadas writes, “I wanted him to say more, but I didn’t want to put words in his mouth, so I just agreed.”