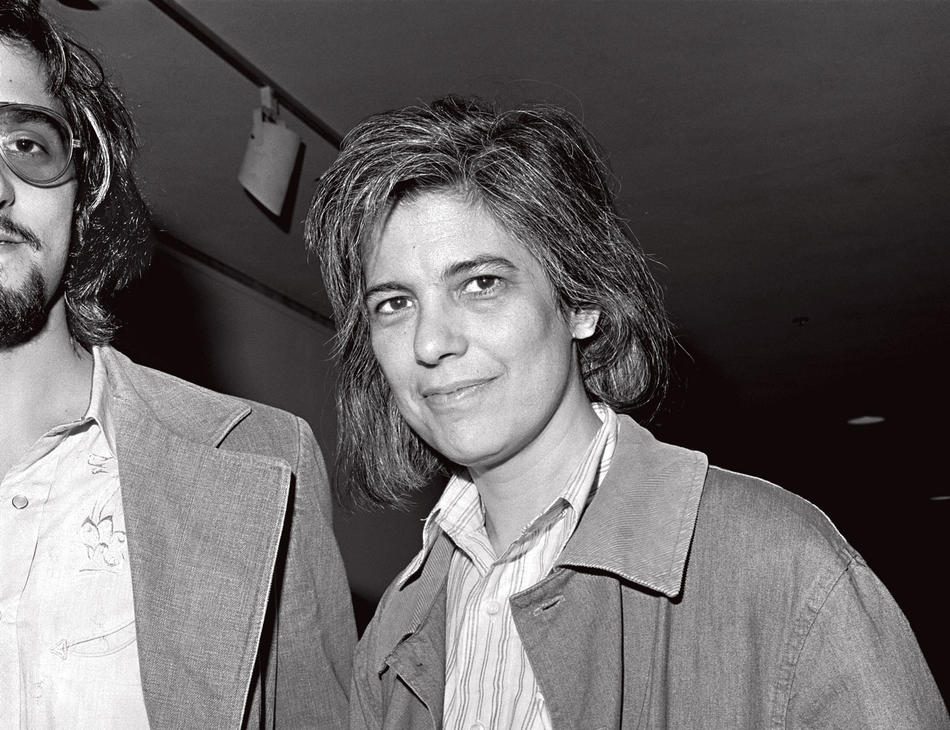

How do you write about a cultural icon — an icon who was also your boss, your boyfriend’s mother, and your roommate, all at the same time? This is the challenge that novelist Sigrid Nunez ’75SOA sets up for herself in Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag. Even those who’ve never read a word of Sontag’s writing will know about her mighty intellect, her charged sex appeal, and that striking skunk stripe that ran through her hair. But few will know the Sontag shown in these pages.

In 1976, Sontag, who had taught in Columbia’s Religion Department from 1960 to 1964, was recovering from breast cancer and a mastectomy and needed help with correspondence. Nunez was 25, a year out of Columbia’s MFA program, and was working at the New York Review of Books. An editor told her that Sontag, one of the paper’s contributing editors, was looking for an assistant, so Nunez was dispatched to Sontag’s large and light-filled penthouse apartment on Riverside Drive at 106th.

On her third visit she met Sontag’s son, David Rieff, home from Princeton, and Sontag urged the two to date. Within a few months Nunez moved into Rieff’s bedroom, and Sontag gave her a private study for her work and the promise of a mentor-student relationship. It’s easy to see why Nunez would accept the proposal, although soon the three were living together in a strange ménage à trois of the mind, both women battling for Rieff’s attention when he was there and finding an odd camaraderie when he wasn’t.

The Sontag who emerges from Nunez’s pen is brilliant and intimidating, needy and self-absorbed, arresting and horrific. Nunez makes allowances for the fact that the 43-year-old woman was recovering from cancer, getting over a broken love affair, and feeling lonely. But Nunez is skewering when it somes to Sontag’s relationship with Rieff. Contrary to Sontag’s claims in conversation with Nunez and others of being a superb mother, Nunez lets her hang herself with her own words: “When I was writing the last pages of The Benefactor, I didn’t eat or sleep or change clothes for days. At the very end, I couldn’t even stop to light my own cigarettes. I had David stand by and light them for me while I kept typing.” Nunez quickly reminds us, “When she was writing the last pages of The Benefactor, it was 1962, and David was 10.”

Sontag is desperate for Rieff to stay on at the apartment, and it becomes painfully clear that Nunez is simply one part of the overbearing and intrusive mother’s plan to keep her only son close. If Rieff wants to learn to ride a motorcycle or play tennis, Sontag wants to be his partner. “She referred to the three of us as the duke and duchess and duckling of Riverside Drive,” Nunez writes.

“I knew that wasn’t good.” Nunez eventually moves out; the relationship with Rieff “staggered on for another year and a half” but finally ended, too. Years later, a friend of Sontag’s reminisced, “Of course, from the day you moved in with them, we all just looked on in horror.”

Much of the book is devoted to drawing a portrait of the strange allure that made it possible for Sontag to coax Nunez in. As a protégé, Nunez doesn’t find beauty in Sontag’s writing, but she is inspired by her fierce intelligence and seriousness. Nunez shows Sontag as a frustrated writer, who often feels passed over for literary laurels. “For most of her life, she felt, her work had not been fairly rewarded. She had no real financial security until she was well into her 50s,” Nunez writes. This novice seems to have spent much of her time with Sontag scrutinizing what it means to be a female writer, lessons ultimately more valuable to her than those of craft. There is an awe that pulses through most of the book, tinged with a surprising amount of sympathy for the woman who told Nunez she “had no patience for victims who couldn’t take care of themselves.”

Sempre Susan, born out of an essay, tapers into loosely connected vignettes to unsettling effect, mirroring Sontag and Nunez’s friendship in later years. In memoir, story is used to illuminate the self; Nunez chronicles, remembers, reflects, but ultimately drifts off the page, and it is Sontag who is illuminated. The result is a sensation that wildly echoes the unbalanced relationship drawn between these two women. Just as she was on Riverside Drive, Nunez is ultimately eclipsed, even in her own memoir.