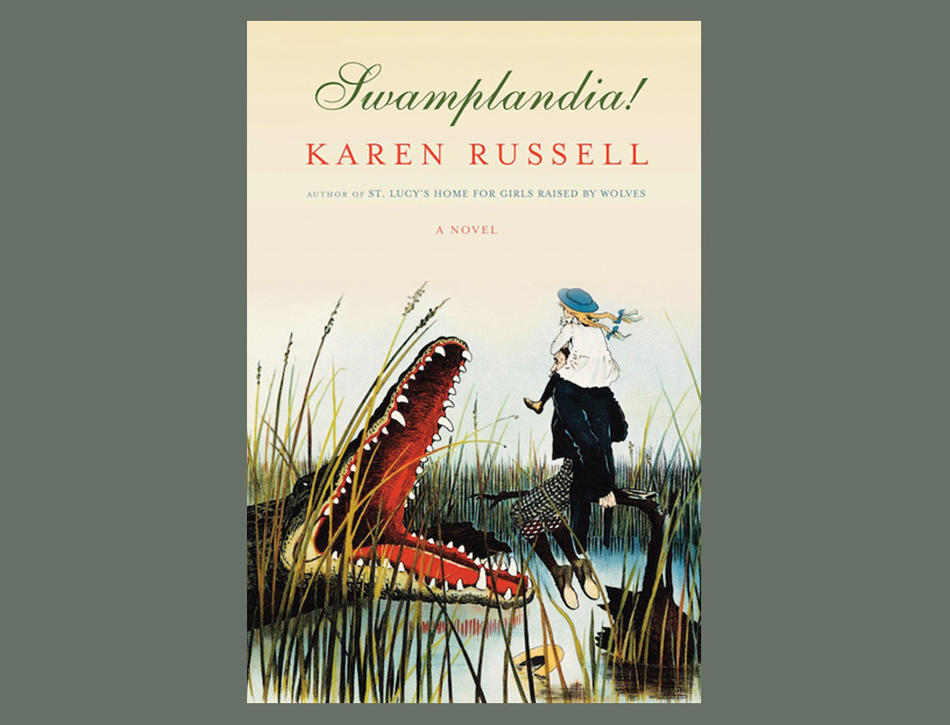

At the start of Swamplandia!, Karen Russell’s debut novel, 13-year-old narrator Ava Bigtree reflects on her family’s unusual business. “Our mother,” she says, “performed in starlight.”

Hilola Bigtree, mother of three and alligator wrestler extraordinaire, is perched on a diving board in the dark, directly above a pool where “dozens of alligators pushed their icicle overbites . . . through over three hundred thousand gallons of filtered water.” Her husband, Chief Bigtree, operates the spotlight while Ava, her older sister Osceola, her brother Kiwi, and 265 tourists look on. Like many other life forms taking hold in the swamp, the Bigtrees are technically a nonnative species. Father Bigtree named himself Chief, and that he prefers that title to Dad speaks to his unusual style of parenting. His own father, Grandpa Sawtooth, left behind debt and a dead-end mining job in Ohio to seek out in the Florida islands the American Eden realtors promised, “with a greed that aspired to poetry.” Instead, he got the island Swamplandia!, where he, his children, and his grandchildren could shed their mainland names and, “without a drop of Seminole or Miccosukee blood, . . . become [their] own Indians.” Like her fictional Bigtrees, Russell ’06SOA builds a beautiful show out of a wilderness scrubland that has been virtually unexplored in American literature.

Swamplandia! is set in the Ten Thousand Islands off Florida’s southwest coast. A region of tiny, marshy isles between the Gulf of Mexico and the wilds of the Everglades, it’s best known for real-estate scams and a natural resistance to the type of development that covers the rest of South Florida. Like the con men who sold underwater plots of Florida swampland to would-be farmers and vacationers throughout the 20th century, Russell convinces her audience that these wild patches can support human life. Swamplandia! is really a story about family — in this case, a family of alligator wrestlers who live on a 100-acre island reachable only by ferry and run a “Gator-Themed Park and Swamp Café.” Ava serves as guide to this world, speaking from her isolated position of adolescence. Because she is so self-sufficient, and her voice so irresistible, the reader trusts her judgment as mature, and winds up believing with her in certain types of magic. She is the best type of unreliable narrator. Through her, Russell is able to explore not only the strange wonders of an alligator swamp, but also the hard difference between innocence and experience, reality and delusion.

If backwater Florida is an American Eden, then Swamplandia! is Paradise Lost. As Ava tells it, her family’s story can be summed up in two words: “We fell.” The heroic Hilola makes it through the pool of gators but is defeated in the first couple of pages by cancer. With its star performer gone, Swamplandia! is no longer able to compete with the Florida Interstate System’s latest attraction — the World of Darkness, a state-of-the-art theme-park Hell that draws visitors to such amenities as a “Tongue of the Leviathan” ride and “Faustian bargain fish tacos.” And with their mother dead, Ava, Osceola, and Kiwi are no longer able to rely on much. The slowing stream of tourists dries up entirely, the last one leaving only her hat. Kiwi is able to turn his sadness into anger at his ineffectual father, and also leaves Swamplandia! for the mainland, where he takes a job with World of Darkness in an attempt to save his family from financial ruin. Chief Bigtree soon follows, on a similar but separate “business venture.” The sisters are left behind on the island: Osceola, 16 and lonely, finds a book called The Spiritist’s Telegraph and begins to communicate with, then romance, a series of ghosts. Ava, meanwhile, is fierce and tragically hopeful in her attempts to keep the park running and the gators fed.

In Russell’s novel, the concrete mainland that Kiwi Bigtree inhabits is just as weird and fantastic as the ever-shifting swamp. Russell alternates chapters between Ava’s story and Kiwi’s story, told in the third person, but it is Ava’s adventures in the sunny, ghost-and-alligator-inhabited islands that seem more truthful. When applied to dry land — specifically, the World of Darkness in which Kiwi toils — Russell’s wild aesthetic reads more like wacky satire. For the reader, the story cannot be resolved until brother and sisters meet again in the swamp, after they have gone, in their different directions, to Hell and back.

Russell has said that Katherine Dunn’s 1989 novel Geek Love made a lasting impression upon her, and like it, her novel uses powerful, inventive language to earn a reader’s emotional investment in the outlandish. It’s through her language that Russell is able to produce a moving, haunting, familiar family story set under unusual circumstances. Consider Ava’s description of a “bend in the channel, where dry grass exhaled yellow butterflies.” Or a cyprus dome: “The interior trees in a cyprus dome are one hundred feet tall, with roots, or ‘knees,’ that stick out of the water and breathe for them; with their veins of vines they look like petrified rain. Really, it feels like you’re walking through the weather of the dinosaurs. The gray-blue fossil of a storm, now dropping small leaves. I watched my sister stand The Spiritist’s Telegraph against a live oak, her mouth full of flowers.”