Of all the mind-bending, boundary-busting trends to come out of the conceptual-art movement of the 1960s, one of the more enduring and yet lesser known is the “artist book,” which, loosely defined, is a book so unusual in appearance and design it is regarded as an object of art. Some artist books don’t really function as books at all — their pages may be encrusted with jewels, lacquered together in immovable clumps, or hollowed out to make images appear in relief — and so might better be described as sculptures that play off our expectations of what books are supposed to look like and how they are supposed to work. Even those artist books that can be flipped through and read in a conventional manner aren’t meant to be experienced as mere containers of information.

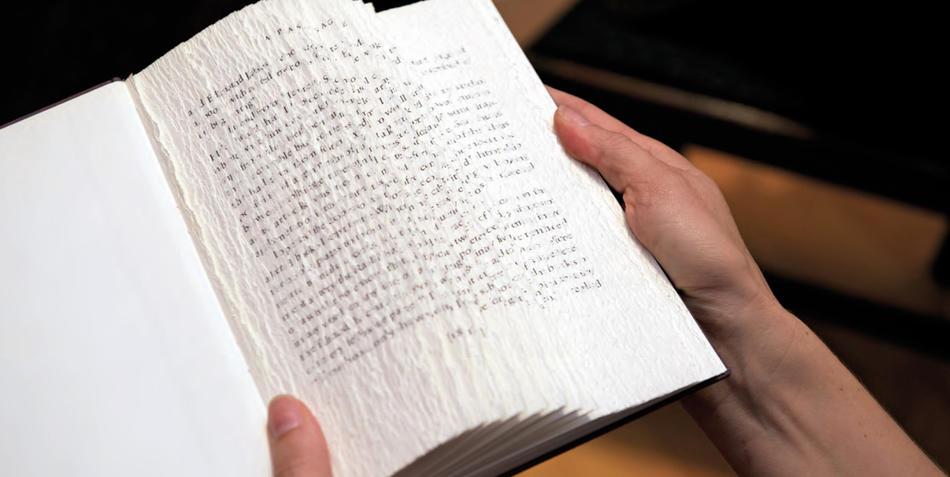

“The paper, the typeface, the binding, the printing, how the words and pictures are arrayed on the page, and how the book feels in your hands — all of these elements get pushed to the foreground in artist books,” says Karla Nielsen, a curator at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML).

A few months ago, the RBML acquired the archive of one of the most important artist-book publishers operating today: Granary Books, a small New York City–based press that, under the guidance of its longtime director and lone editor Steve Clay, has produced some 125 artist books over the past three decades. Granary’s list of authors reads like a who’s who of the genre. Susan Bee, Johanna Drucker, Emily McVarish, George Schneeman, Buzz Spector, Cecilia Vicuña, and Jonathan Williams are among the dozens of book artists to release work through Granary.

Published in limited editions of as few as twenty-five or fifty copies, the artist books that Granary puts out aren’t found in bookshops; most of them are sold directly to museums, libraries, and private art collectors, typically for a thousand dollars or more apiece. This allows Granary and its affiliated artists to invest great effort and expense in producing them. The painter Susan Bee, for instance, hand-painted all the artwork in each of forty copies of Talespin, a 1995 Granary title that presents her darkly humorous scenes of sex and romance beneath snippets of traditional nursery rhymes. Similarly, the sculptor Buzz Spector, in creating A Passage, from 1994, meticulously tore every page in its forty-eight copies so that they start off as flaky stubs and gradually get wider; the effect is that a short essay by Spector about the limitations of visual perception and memory, which was printed identically on every page before Spector ripped them, is fully readable only at the end of the wedge-shaped volume.

“If you’re working with a painter, why not treat the book as a collection of original paintings?” says director Clay, sixty-three, who still runs the press out of his SoHo loft. “If you’re working with a sculptor, why not explore the book’s sculptural properties?”

The Granary archive, which will be accessible to researchers this fall, consists of nearly one hundred boxes of sketches, galleys, manuscripts, and correspondence from the production of all the company’s titles, which also include a few volumes of contemporary poetry and books about bookmaking. Of particular interest, Nielsen says, are letters and e-mails exchanged between Clay, book artists, and craftspeople involved in each work. “One of the revelations here is the very active role that Clay often plays in helping artists imagine what the book medium is capable of,” she says. “He’s at the fulcrum of a collaborative process that involves paper suppliers, printers, binders, typographers, and other artisans involved in realizing an artist’s vision. How their contributions are brought together has a direct bearing on the artistic result.”

On a recent afternoon, Nielsen showed a reporter some of the Granary artist books at the RBML. (The library now owns one copy of each.) They are, without exception, beautiful. Some are printed on luxuriant, heavy-gauge paper and hand-bound between covers of fine cloth. These tend to reveal their surprises slowly; viewed upon a shelf, they resemble books published by any boutique press. Others are more outwardly radical-looking. The Dickinson Composites, by Jen Bervin, from 2010, consists of a rectangular container, about the size and shape of an LP box set, with six cotton quilts nestled loosely inside. The quilts, which are the size of letter paper and removable, are embroidered with red-silk dashes and crosses arranged in seemingly haphazard ways. In fact, each quilt is a facsimile of one of Emily Dickinson’s handwritten poetry manuscripts, except enlarged and with all the words removed. What remains are the poet’s peculiar punctuation marks — dashes of varying lengths and plus signs — whose intended meaning scholars have long debated and which are omitted from most printed versions of her poems.

“Choosing to circumvent what seemed like an intractable editorial situation, I tried to make something as forceful, abstract, and generously beautiful as Dickinson’s work is to me,” Bervin once wrote.

But is it a book?

“It’s a book in the sense that it collects a series of discrete pieces of information and makes them cohesive, transportable, and preservable,” says Nielsen, using a broad definition of the term that historians of bookmaking also apply to ancient scrolls and to other devices for carrying large amounts of information, such as the concertina-like paper-folding systems and inscribed fans that were once common in the Far East.

Now that the form of book we’re most familiar with, the codex, has hit the end of its nearly two-thousand-year reign as the best information-sharing technology around, it makes sense that visual artists today are finding new inspiration in it. For what is a more potent symbol of Western knowledge and culture? How could its demise not be suggestive of our own?

But artist books, according to Nielsen, offer more than a lament. By deconstructing and reimagining the book form, she says, they may provide a window to its future.

“Mainstream publishers are realizing that now that readers have the option of reading digital text, they are less likely to buy printed books unless those books have some value as an object, aesthetic or functional,” Nielsen says. “These Granary publications focus our attention because they are beautiful, but also because they ask us to think about the codex as a format. We read a poem differently across a page spread than we do across a scrolling Web page.”