The subjects of your three books so far — Jesse James, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and now George Armstrong Custer — are all icons who rose to prominence in the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction. What draws you to this period?

I was thinking about this recently in relation to a British novel called The Wake, which is described as a “post-apocalyptic” novel set in England after the Norman Conquest. The idea of a historical period being apocalyptic fascinates me, because that’s exactly how I see the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. People lived through a total destruction of the political, social, and economic order, out of which a completely new world arose. My books look at this period as the making of the modern United States.

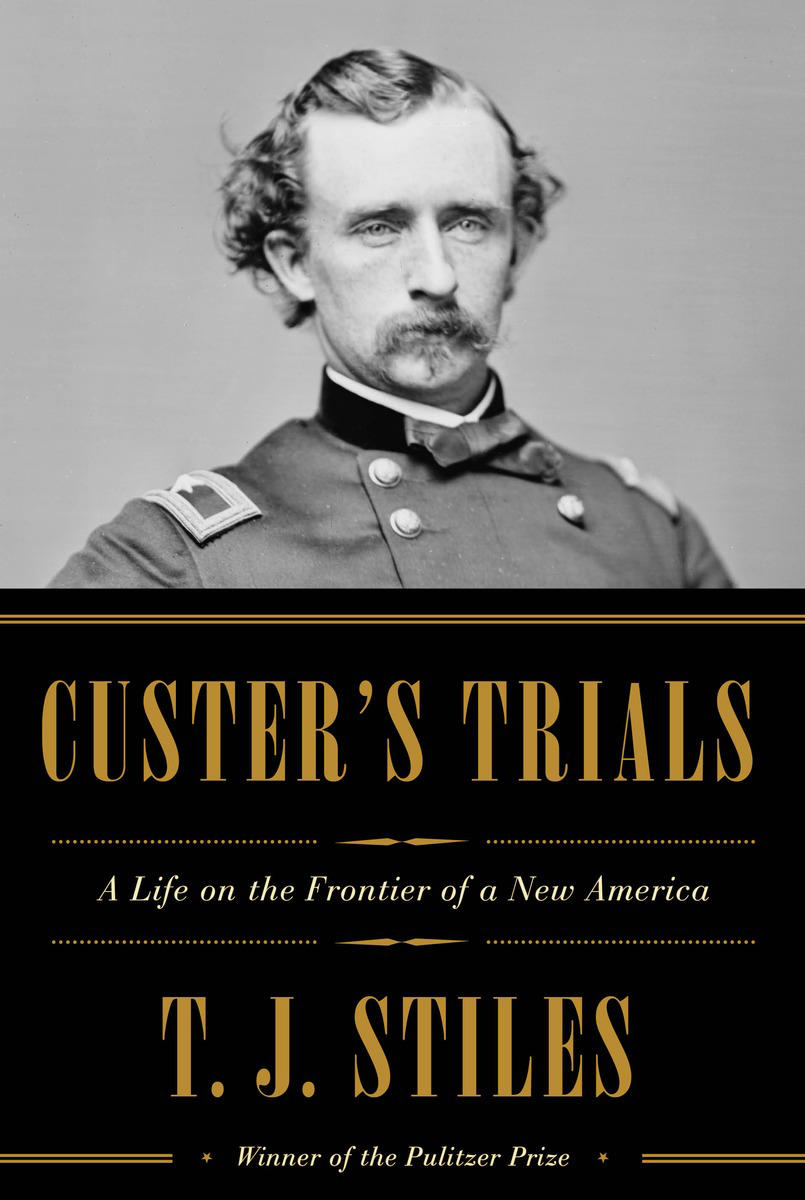

You say in the book’s preface that this portrait of Custer is not so much a debunking of previous interpretations as an adjustment of the camera angle. What’s different about your take?

One critical difference is that I frame his story within a time rather than within a place. The book doesn’t debunk the idea that Custer was an important figure in the West — he was — but his life also reflected a much broader change in America.

I also found it fascinating that this antebellum figure — Custer was more Southern cavalier than industrializing Yankee — was so immersed in all these aspects of modernity as it was emerging. He wrote for the national magazines that were starting up after the Civil War; he was active on Wall Street, trying to launch a silver mine and then playing the stock market; he not only explored the West and fought the Native Americans there, but he also defended the transcontinental railroad, in the field and in print.

As you point out, he dabbled in modernity but couldn’t adapt to it. He’s a baffling figure in so many ways: this is someone who in the Civil War engaged in hand-to-hand combat on horseback — a pretty grim experience — yet his writing about war is so florid and romanticized.

Yes, Custer may be the last American general to actually kill an enemy with a sword.

What’s romantic about that?

Custer was flamboyant, and that’s a problematic concept for us today. We tend to believe, “big show, hollow man.” But in an earlier, more self-consciously traditional culture, Americans expected and admired the big, self-important speeches in Congress, the dramatic gestures, the exaggerated appearance of a public figure. In retrospect, things often look ridiculous that had good reasons for existing at the time — the outrageous costume Custer wore into battle, for instance. Yes, people made fun of it. But his men could see him in combat; they knew where he was. It was a declaration of his confidence in the one area in which he consistently performed well — fighting.

Custer’s wife Libbie is perhaps the book’s most intriguing figure — highly educated, exceptionally tough, a gifted writer, yet ultimately careful not to eclipse her husband in any way. And like him, she held some appalling views about African-Americans, including Eliza Brown, the escaped slave who so capably managed the Custer household. How were you able to create such a vivid portrait?

When I started work on Custer’s Trials, I thought: finally, I get to write about women! The sheer volume of documentation of Custer’s life — personal letters and Libbie Custer’s memoirs, which she published after her husband’s death — allowed me, for the first time, to make the women in my subject’s life three-dimensional characters central to his story. Libbie’s writing about her complicated, often tense, sometimes mutually supportive relationship with Eliza brought a kind of literary depth to the story that I relished as a writer.

Custer’s defeat at the Little Bighorn is, of course, the one part of his story that people know going in. But in the book, you don’t describe the battle. Why did you make that choice?

Robert Utley, the great historian of the American West, read the manuscript and told me that he was glad that I didn’t try to re-create the Little Bighorn because he would have disagreed with me no matter what I wrote. I could have very easily gotten lost in the Little Bighorn. But Utley’s right: no one can write a convincing account. Instead, I tried to find a way to convey the feeling that Americans had — that it was a strange, inexplicable event that took place offstage.