Columbia’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture and the Museum of Modern Art asked five architect-led teams of urban thinkers to reimagine the suburbs in light of the foreclosure crisis. The result, Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream, currently on exhibit at MoMA, has inspired new discussion and new thought — and created a few subdivisions.

I. The Buell Hypothesis

On February 18, 2009, the day after President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, two of history’s most stimulating conversationalists got stuck in traffic on I-95 South. Socrates, the Greek philosopher, and his pupil Glaucon, son of Ariston, were headed to Athens, Georgia, for a symposium on housing and the American suburbs. The men took note of their surroundings along the highway — the grassy berms, shopping malls, and housing developments riddled by foreclosures — and broke into a dialogue on the assumptions that underlie the American Dream.

So begins The Buell Hypothesis, a four-hundred-page book produced by Columbia’s Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture. “The suburb is organized around an ethos that construes homeownership, or at least the feeling of being at home, as something essential or fundamental,” says Socrates, scrutinizing the roots of happiness as he used to at Polemarchus’s house. “However, the financial crisis has made clear that the houses in and through which Americans dream their dreams are not owned by them but rather by banks, whose octopus-like networks make a mockery of national borders, never mind national ‘dreams.’” The American Dream “is a fiction, but a real one,” Socrates says, a kind of movie, profitable and risky, “requiring tax incentives and other types of government support to prop it up and to keep it running in theaters nationwide.”

Change the dream and you change the city: this is the central premise of The Buell Hypothesis, which is written in the form of a screenplay as an alternative to the old metaphorical script that equates homeownership with happiness and full civic participation. Supplemented by a montage of newspaper clippings, photographs, and other documents, The Buell Hypothesis examines the housing crisis through playful Socratic argument and tells the story of public housing in America from the Great Depression to the Great Recession — how failed housing projects were demolished or privatized, their bleak examples (most notably, the Pruitt-Igoe complex in St. Louis) held up to discredit the very idea of public housing.

To challenge that narrative, the Buell authors — Buell Center director Reinhold Martin, Anna Kenoff ’07GSAPP, and Leah Meisterlin ’09GSAPP — identified eight distinct suburbs marked by high foreclosure rates, potential access to high-speed rail, and large tracts of public land, to present test cases for reinvention at a time when stimulus funds had begun flowing to infrastructure projects.

Socrates, in the passenger seat, argues that the boundaries between suburb and city, private and public, are blurrier than we might think, and that the suburbs, with their cul-de-sacs and idyllic street names and promises of escape, belong to “the same world systems that have produced megacities with vast urban slums.” The house, Socrates points out, while imagined as one’s freestanding castle, is a profoundly public object — surrounded by public land, served by public roads and schools, subsidized through tax deductions — and is the site, whether at the kitchen table or at the home computer, of the most public act of all: the exchange of ideas.

“So those who believe that the only options available to us must originate within the marketplace are mistaken,” Socrates says. “Publicly supported universities, public schools, even the interstate highway system, all hint at other options. But these options will only become viable if values other than financial profit become common sense, and that can only happen in and through a reclaimed public sphere.”

Where are you going, Socrates? And don’t say Athens.

II. Public Dreams, Private Needs

“In the end, Socrates asks, what if there were public housing in the suburbs in response to the foreclosure crisis?” says Reinhold Martin, an associate professor of architecture at Columbia, in his office on the third floor of Buell Hall. “And that is left as an open-ended question rather than a direct proposal.”

The Buell Hypothesis grew out of discussions on public housing that the center had begun generating in the fog of the subprime mortgage implosion of 2008. The hypothesis was fourfold: that globalization affects the inside as well as the outside of a house; that the suburb is a kind of city; that all houses are a type of public housing; and that you change the city by changing the cultural narratives behind the single-family house.

“The house is a sacred term in American public discourse,” says Martin. “But a house could just be a house, like a car, or a chair, or a computer. It doesn’t necessarily bring with it — nor should it, I think — transcendent social meaning. A house isn’t sacred: it’s just one among many artifacts with which we live. You could say that we have attempted to gently secularize the idea of the house.

“The ownership-based housing model has consequences in architecture. You could ask, what is the type of architecture that corresponds with this political economy — more or less the suburban house. Or you could go the other way and look at a house or any work of architecture and ask, what kind of a world does this building belong in? What does it imagine?

“That was partly our point in insisting that all kinds of housing, including the suburban house, are forms of infrastructure: they connect with, and are made possible by, the larger systems that are supported by the public sector. The myth of individual determination and freedom is precisely that: a myth.”

In late 2009, Martin compared notes with Barry Bergdoll ’77CC, ’86GSAS, professor of art history and architecture at Columbia, and MoMA’s curator of architecture. Bergdoll was organizing a series of public issues–based shows at the museum, and Martin was developing a research project on housing at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation’s Studio-X New York that yielded a pamphlet called Public Housing: A New Conversation. Together, they conceived and planned Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream. They selected five teams led by architects and including economists, housing activists, public-health experts, and engineers, and furnished them with The Buell Hypothesis. The teams, three of them headed by Columbia architects, read the work, chose suburbs, and, on the basis of their interpretations of the text, designed what the Foreclosed curators cannily call “provocations,” as opposed to “projects.”

“When people hear ‘project,’ they think that it’s meant to be built tomorrow,” Martin explains, “and these are not to be built tomorrow. It’s not that they couldn’t be built. It’s not that they’re unrealistic. It’s that they really are interventions in the space of the museum, in the discourse of architecture, and in other areas of the public sphere.”

III. Public Outcry!

The provocations lived up to their name. The show was widely praised in the media for its ambition, vision, and social and environmental engagement, but there has also been some dust raising on the architectural blogs. Dissenters called the proposals out of touch, self-indulgent, elitist, esoteric. Some saw a cabal of ivory-tower types imposing their social-engineering fantasies upon a constituency they don’t know or understand. Others confused a theoretical exercise meant to incite discussion with a shovel-ready project.

Martin has been taking the attacks in stride. “It’s a kind of cliché to describe this whole endeavor as elitist,” he says. “I’m not going to pretend that MoMA and Columbia are not, in effect, elite institutions. But the effort has been to call the elite institution to its responsibilities, both here and at MoMA. I think Columbia has significant responsibilities with respect to the housing crisis. We could do more to support the very idea of public housing, given that our neighbors are in danger of losing their housing through policies that have afflicted housing complexes in other parts of the country, where it’s either demolition or privatization.”

For Martin, the vitriol on the Internet illustrates how public discourse on housing crumbles at its foundation. “What hasn’t been asked is, what is the role of the government in addressing the housing crisis?” Martin says. “Again, that’s a question we’re barely able to enunciate in public because of the stigmas associated with public housing and the durability of the fetish of the single-family home. You can see from some of the reactions that we were denounced for asking that. There was a certain amount of name-calling. That is not surprising, but it’s interesting: even though these are hypothetical projects, they draw out the political contours of the country. They draw out different strategies: more activist strategies that consider this to be fiddling while Rome burns, purely academic speculation that doesn’t take into account the voices of the people who would actually live in these places.

“Certain fault lines will always be hard to overcome. One is the genuine suspicion that many activists have toward settings like MoMA or Columbia, whatever our intentions may be. Learning how to overcome those suspicions, to work together productively and critically, and, most important, to confront our own contradictions, is something we can all do, including the well-intentioned activist.”

IV. A Public Option?

In the end, Foreclosed might be remembered as much for what it says about economic and cultural life in America in 2012 as for its bold conceptual designs.

“Foreclosed demonstrates the tools that are available under current conditions,” says Martin. “The teams have been very innovative within the market parameters, using land trusts, co-ops, real-estate investment trusts — various forms of communal ownership intended to empower the residents.”

But for Martin, one possibility was conspicuously absent. “In my view, some options were overlooked, like public housing. I’m not surprised, but it’s a fact. Despite our encouragements — we even provided publicly owned land, and identified sites that were either publicly owned or under the supervision of the local municipalities — in virtually all cases that alternative was sidestepped. So the results have proven that it’s very difficult to contemplate options outside the market.

“That’s the bottom line: the option of public housing is not currently available in the mainstream.”

Outside the Box

Three teams led by Columbia architects propose daring new models for suburban living.

Simultaneous City

Temple Terrace, Florida

Firm: Visible Weather

Architects: Michael Bell, professor of architecture at Columbia, and Eunjeong Seong ’02GSAPP

Foreclosure rates are high on the Tampa–Temple Terrace border. Here, Temple Terrace’s suburban single-family houses meet Tampa’s recent condominium conversions — the last homes to be sold before the crash and the first to fail afterward. We propose that Temple Terrace suspend its current public-private partnership (a 225-acre commercial redevelopment on land the city plans to give over to a private developer) and instead redevelop this border with a dense housing stock, creating a walkable urban area on city-owned land, with private housing for sale and rent. Our proposal is not about changing a 1950s suburb into a city, or critiquing suburban culture from an urban perspective, but rather sparking innovation in housing design by reversing the notion that public-private development models are more creative than purely public ventures.

We propose a zone in which a diversity of housing, retail, and government buildings would fuse so that all could share a deep well of financial resources. These resources, in time, could fund innovation in energy management, structural design, and housing. We envision a three-level structure topped by eighty-eight courtyard houses that form the roof of office spaces and a new city hall. By recapturing underused space (parking lots, sidewalks, setbacks), this plan could bring ten thousand new residents to the area adjoining the Tampa border, expanding Temple Terrace’s population by 40 percent.

The development at Temple Terrace could work on both a macro and a micro scale, creating a large-scale housing development that is diverse and responsive to need, and thus more financially stable than the housing models that are ubiquitous today.

Thoughts on a Walking City

The Oranges, New Jersey

Firm: MOS

Architects: Hilary Sample, associate professor of architecture at Columbia, and Michael Meredith

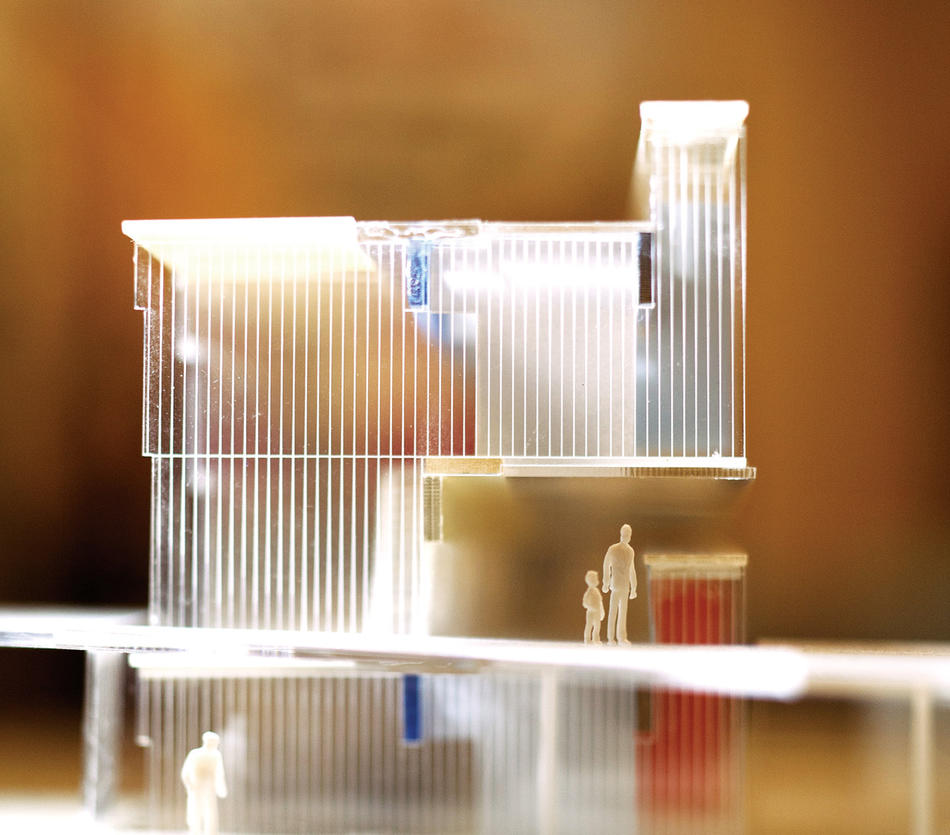

The City of Orange — more urban than suburban — is linked to New York City and Newark by commuter rail but is nonetheless struggling with foreclosures, vacancies, property abandonment, lack of fresh food, and social isolation. By turning underused streets — a significant expense for the city — into sites of redevelopment, we seek to redirect homeownership toward a dense environment rather than individual enclaves. People converge around courtyards and public spaces, and walking becomes a principal mode of transport.

The housing, a series of structurally solid units, is designed with floor-to-ceiling windows to provide health-giving light and air. Gardens permeate the ground floor and continuous roof surfaces. The courtyards, formed by the angled units, provide additional garden spaces linked to the adjacent vacant and overgrown lots. The idea is that private space that is now abandoned, foreclosed, or empty would be given back to the public. Through a shared-equity model, units are developed for either living or work, with ground-floor commercial space and open-air passages so that people can walk between buildings. The units are meant to be modified by residents, as in Le Corbusier’s Quartiers Modernes Frugès in Pessac, France.

Nature-City

Keizer, Oregon

Firm: WORKac

Architects: Amale Andraos, assistant professor of architecture at Columbia, and Dan Wood ’92GSAPP

Recognizing the failure of our current suburban landscape — sprawling single-family homes that have become untenable both environmentally and economically — Nature-City reinvents the British urbanist Ebenezer Howard’s late-nineteenth-century model of the “town-country” for the twenty-first century, building upon the long-standing dream of living closer to nature by emphasizing land stewardship and sustainability.

To do so, Nature-City integrates housing and ecological infrastructure to provide five times the density and three times the public open space of its neighboring Keizer. Nature-City extends a series of urban “piers” into restored native habitats — an oak savanna, wetlands, a Douglas-fir forest — to create a neighborhood in which more than 70 percent of the land is dedicated to nature. Within each band of city, a wide range of housing blocks provide various landscapes, such as sky gardens and orchard courtyards. In addition, the housing itself behaves as ecological infrastructure, treating organic waste in the compost dome, generating electricity using methane, storing treated water in towers. With its embrace of density (of humans, animals, and plants) and diversity (of uses, housing types, and habitats), Nature-City creates a community grounded in difference rather than sameness, and promotes a renewed investment in public life.