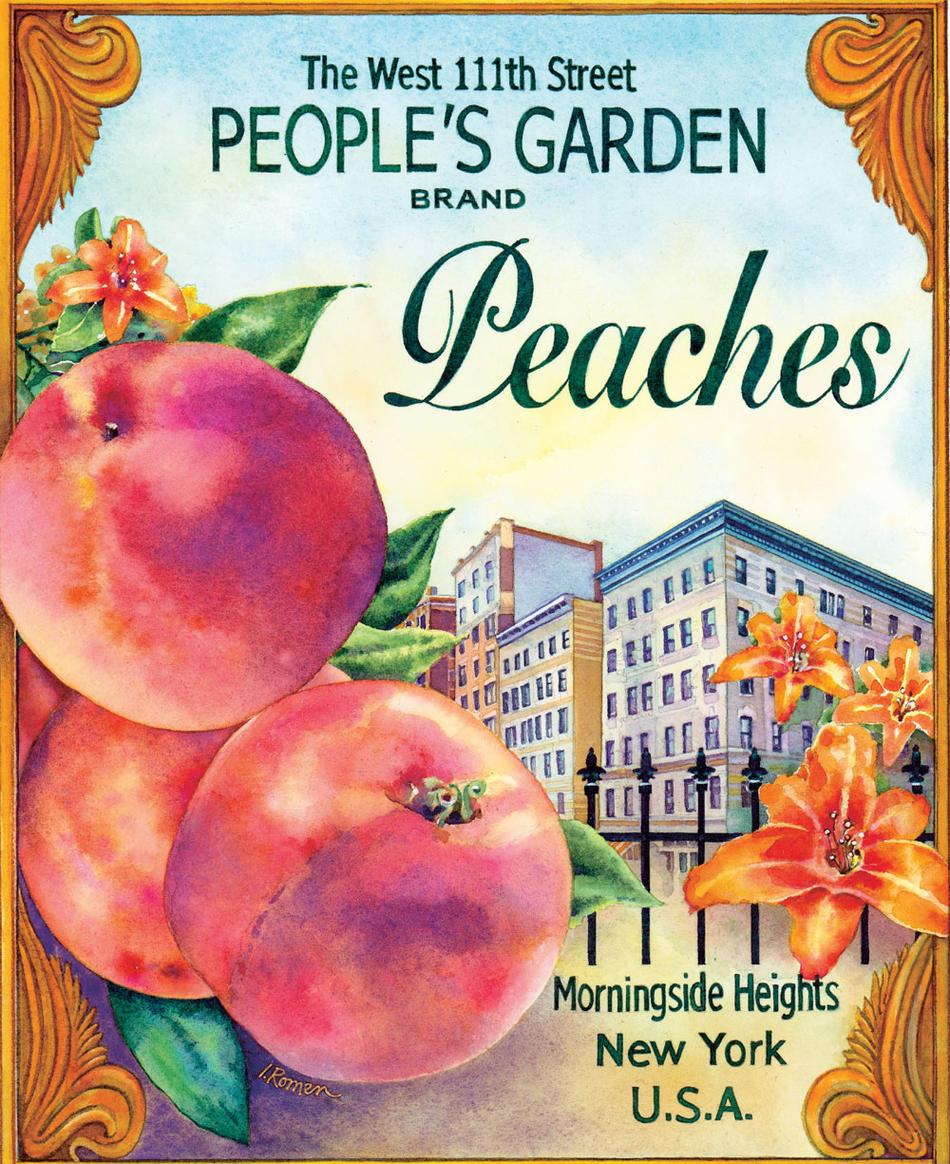

Among the nearly 600,000 London planes, honey locusts, maples, and other trees in New York City, there is one, barely 15-feet tall, that causes a buzz in Morningside Heights every summer. The tree sits in the West 111th Street People's Garden, and at any other time of year its spreading crown of green leaves could make it pass for just another crab apple. But in August its fruit ripens, bringing the branches so low over the wrought-iron fence that any passerby can grab a free snack. It's a peach tree, one of two in the area — the other grows at the West 110th Street Broadway mall just down the block.

Although a native to China, and more often seen in California or Georgia, the peach tree has a New York sensibility. It's a self-starter, a loner (it self-pollinates), and its survival relies on a bit of luck. For it to sprout on its own, a pit would have to land on the ground in late October, just in time for several inches of leaves, detritus, and soil to sweep over it. Horticulturalists say that peach pits require stratification, a period of preservation to break the seed's dormancy and promote germination. A cold but dry winter could accomplish this — provided that the pit was in a spot of southern exposure, receiving a lot, but not too much, sunshine. Despite all these variables, a peach tree can fight and grow on its own, but soon its branches become unruly, weighing it down.

This is the condition in which Barbara Hohol '71GS found the two-year-old sapling in the West 110th Street Broadway mall when she took over its care in 2002. "It had grown so sideways its trunk was touching the ground," she recalls. "So I cut it off, making its limb grow upright."

A jewelry maker by trade, local activist by calling, Hohol has been living in the neighborhood since 1960, and began gardening ten years ago in the greenhouse at the Cathedral School of St. John the Divine. As a child she had worked at her father's carnation greenhouse on Long Island. "Really, it's instinctual," says Hohol, adding with a gravelly chuckle, "I must be doing something right because IÕm killing less and less."

Hohol is as opinionated about most things as she is about gardening; Morningside Heights is one of them. She has often been a source for quotation in the New York Times, at turns lamenting the neighborhood's gentrification and Columbia's role in it, then defending the University as an inspiring institution. Her feistiness compelled three reporters to point out the tag on her license plate and e-mail address: GADFLY.

Most recently, her vigilance about gardening - specifically pruning - has caused a stir in the neighborhood. In July, Hohol cut back a wide hedge of rosebushes, much to the consternation of some community leaders who prefer a cloistered shade that blocks out Amsterdam Avenue. Hohol dismisses this as antithetical to good gardening. "Go look at the rosebush; it's being choked by the grapevine and getting back into the forsythia. Those conditions should never — under any aesthetic — be allowed to happen." Others disagreed, exiling Hohol from the garden. This is not the first time she has butted heads with the garden's leadership, and in response, she is petitioning to overturn it.

The garden, according to Hohol, came to existence in the early 1970s thanks to the block's residents, a number of whom were squatting in nearby buildings. "Many were Hispanic, and they planted what they ate," says Hohol, remembering rows of tomatoes, lettuce, beans, and, at one point, even corn. While a number of the original squatters moved out, some remained to become legitimate tenants thanks to city sweat-equity programs. And in the mid-1980s, the garden came under the auspices of GreenThumb, New York's urban gardening project.

Because of its ragtag beginnings, the garden's soil still sits above a layer of rubble from the lot's razed buildings. Neighbors hand-sifted the soil to make it arable, but it's never been tested for toxicity. For this reason, the garden has eliminated all food and remains entirely floral, with orange daylilies, yew, and potted impatiens growing along the walkway.

Except for the peach tree. "It's the icon of the garden,' says Hohol. "Its fruit is the essence of peach, not too sweet. It's worth the risk to eat it once a year."

A local "artist," as Hohol calls her - making quotation marks in the air - claimed to have planted the garden's tree, now probably 20 years old. Hohol doubts this, insisting that the artist, who has since moved away, had too little horticultural sense to have done so. The apple cores, coffee grounds, and eggshells the woman devotedly brought to the tree every day would have made great compost, Hohol says, "but we had to do a great deal of work to convince her that they were doing nothing, just sitting rotting at the trunk."

Hohol recalls a neighborhood celebration ten years ago in the garden, in which she and other gardeners picked enough peaches to make seven pies for the whole block. It was also an acrobatic feat, requiring Hohol to climb a ten-foot ladder steadied by two men. She carried a basket attached to a long pole to make sure she got every last peach. "Those who weren't working came to laugh at me, taking bets whether I'd fall off," she says slyly. "Some of them hoped I would."